READIN', RITIN' AND RIDIN'

This School System Thinks Motorcycles and Safety ARE Compatible

JACK SCAGNETTI

MOTORCYCLING and safety can be compatible. It’s all a matter of proper education. Federal legislation for highway safety requires states to implement motorcycle safety, including special licensing through special examinations. Some 25 states already have put into effect laws which require a special license or license endorsement for motorcycle operation, and an equal number require the wearing of safety helmets.

A public instruction program on motorcycle safety, offered by the West Valley Occupational Center, Woodland Hills, Calif., may be expanded and adopted in the Los Angeles city schools’ driver education program. Offered by the City Schools Adult Education Division, in conjunction with San Fernando Valley State College, the Auto Club of Southern California and the California Motorcycle Safety Council, the six-week course drew 49 applicants in its initial trial. A second six-week course was started immediately afterward.

School, safety and Auto Club authorities have been watching the program closely, and say it could well serve as a model for motorcycle safety education throughout the nation. They are agreed that motorcycling can be safe—if drivers are properly educated in basic fundamentals of cycle operation and traffic rules.

The instruction program was inaugurated after accident records revealed that the majority of cyclists were not schooled in proper use of their vehicles. They were not familiar enough with the cycle’s operational procedures or basic riding rules. Many were riding rented or borrowed motorcycles.

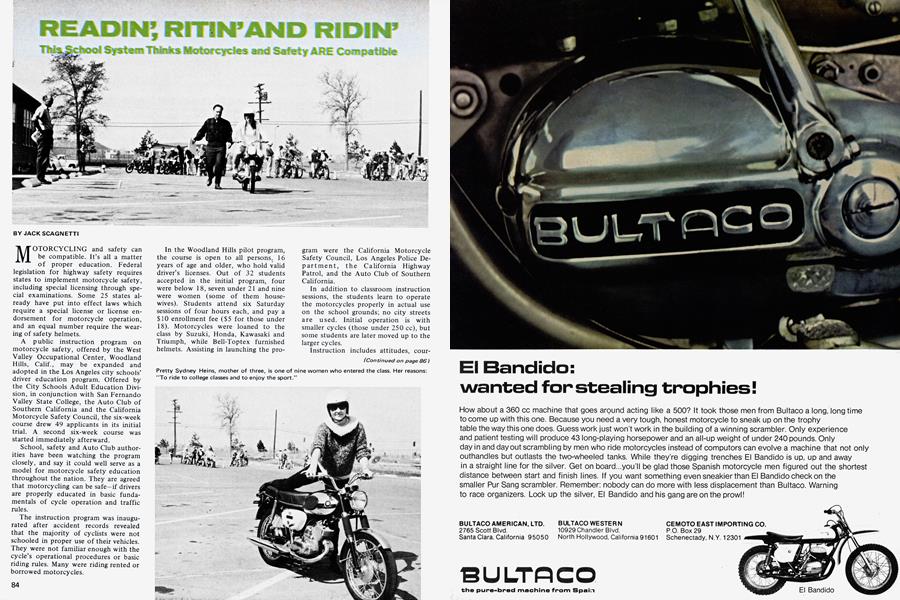

In the Woodland Hills pilot program, the course is open to all persons, 16 years of age and older, who hold valid driver’s licenses. Out of 32 students accepted in the initial program, four were below 18, seven under 21 and nine were women (some of them housewives). Students attend six Saturday sessions of four hours each, and pay a $10 enrollment fee ($5 for those under 18). Motorcycles were loaned to the class by Suzuki, Honda, Kawasaki and Triumph, while Bell-Toptex furnished helmets. Assisting in launching the program were the California Motorcycle Safety Council, Los Angeles Police Department, the California Highway Patrol, and the Auto Club of Southern California.

In addition to classroom instruction sessions, the students learn to operate the motorcycles properly in actual use on the school grounds; no city streets are used. Initial operation is with smaller cycles (those under 250 cc), but some students are later moved up to the larger cycles.

Instruction includes attitudes, courtesy and responsibility of the rider; dressing for the ride with proper protective clothing and helmet; pre-start safety check of the motorcycle, which involves nine separate items to remember to do; explanation of basic types of motorcycles; safety films; demonstrations by instructors on safety checks, use of eyes, use of mirrors, over-theshoulder glance, and blind spots; turning by leaning and by steering; gear changing; figure-eight and circling demonstration; and parking and locking properly.

(Continued on page 86)

Continued from page 84

Additional instruction features include discussion on friction, momentum, inertial starting, stopping distances, force of impact ratios, why and how to maintain control on a curve and related laws of physics in relation to safe sportcycling. Defensive driving is stressed as many motorcycle accidents are not really the fault of the cyclist, but rather of hazards he is likely to encounter. Hazards include objects on the roadway, children playing, dogs, bicycles, tracks and metal surfaces, car doors and emerging passengers, blind spot dangers, and narrow roads in the mountains. The safety pattern for riding in groups is stressed. Trail and dirt riding procedures, plus slalom riding through pylons, are outlined in detail. Motorcycle maintenance and types of engines are studied.

Statistics on motorcycle accidents, gathered from reports by the National Safety Council and a study by the California Highway Patrol, reveal some interesting facts and figures:

(1) In 1960, there were 575,500 motorcycles registered in the U.S.; by 1966, the total reached 1,914,700. Deaths involving motorcycles totaled 2160 in 1966, an increase of 210 percent since 1961.

(2) Motorcycle drivers, when involved in an accident with another type of vehicle, were considered by investigating officers to be at fault less than half of the time, reports the highway patrol study.

(3) During 1966, 44 percent of motorcycle drivers involved in fatal and injury accidents were between 16 and 20 years of age, compared to 17 percent of all other drivers.

(4) Among the surveyed motorcyclists who wear helmets, 14 percent suffered head injuries, as compared to 31 percent among those who do not wear helmets.

(5) Studies show major contributing circumstances to cycle accidents are speeding, failure to yield right-of-way and inattentive driving.

An interested observer at the Woodland Hills pilot instruction program which this writer attended was Amos E. Neyhart, a professor at the University of California at Los Angeles, who is director-emeritus and consultant of the Institute of Public Safety at Penn State University. For 33 years he was a consultant on driver education for the American Automobile Association (AAA), and is considered the father of public school driver education. He first launched a driver education class in high schools in 1933 in Pennsylvania. Neyhart praised the Woodland Hills program and said, “It could well serve as a model for other such public instruction courses throughout the nation.” The Motorcycle, Scooter and Allied Trades Association, in a summary of legislation, recommended special training and testing of operators prior to licensing. In addition to being fun, cycling can be safe. It’s all a matter of public education. A coordinated effort by school, police, safety and other public officials, perhaps encouraged by civic and service groups along with the general public, could easily ignite a nationwide campaign for motorcycle safety programs similar to the Woodland Hills instruction setup.