HONDA 450 RACER

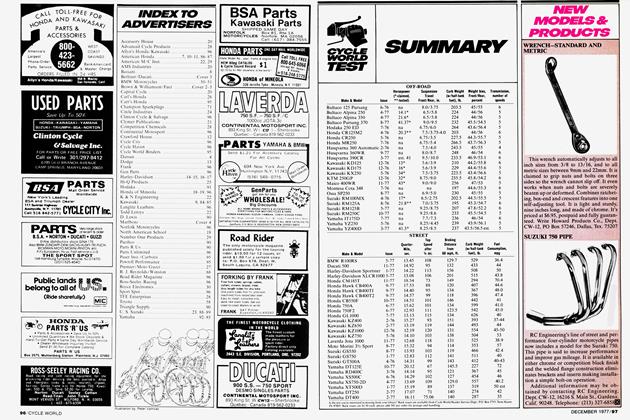

CYCLE WORLD TEST

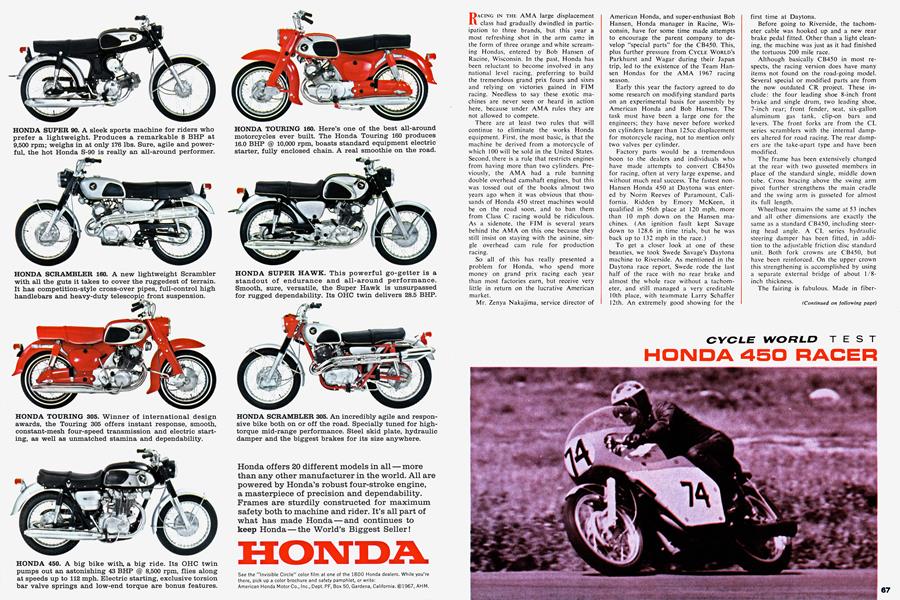

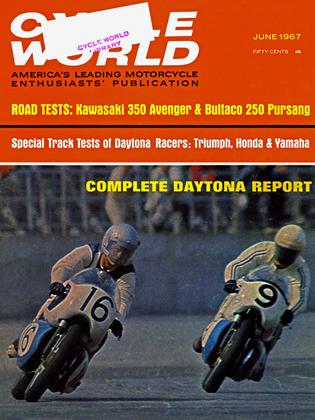

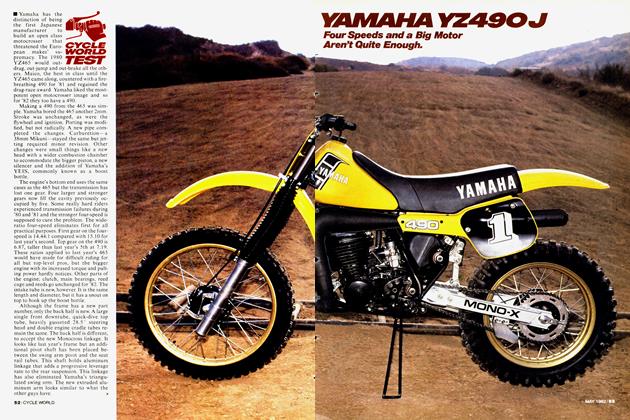

RACING IN THE AMA large displacement class had gradually dwindled in participation to three brands, but this year a most refreshing shot in the arm came in the form of three orange and white screaming Hondas, entered by Bob Hansen of Racine, Wisconsin. In the past, Honda has been reluctant to become involved in any national level racing, preferring to build the tremendous grand prix fours and sixes and relying on victories gained in FIM racing. Needless to say these exotic machines are never seen or heard in action here, because under AMA rules they are not allowed to compete.

There are at least two rules that will continue to eliminate the works Honda equipment. First, the most basic, is that the machine be derived from a motorcycle of which 100 will be sold in the United States. Second, there is a rule that restricts engines from having more than two cylinders. Previously, the AMA had a rule banning double overhead camshaft engines, but this was tossed out of the books almost two years ago when it was obvious that thousands of Honda 450 street machines would be on the road soon, and to ban them from Class C racing would be ridiculous. As a sidenote, the FIM is several years behind the AMA on this one because they still insist on staying with the asinine, single overhead cam rule for production racing.

So all of this has really presented a problem for Honda, who spend more money on grand prix racing each year than most factories earn, but receive very little in return on the lucrative American market.

Mr. Zenya Nakajima, service director of American Honda, and super-enthusiast Bob Hansen, Honda manager in Racine, Wisconsin, have for some time made attempts to encourage the parent company to develop "special parts" for the CB450. This, plus further pressure from CYCLE WORLD'S Parkhurst and Wagar during their Japan trip, led to the existence of the Team Hansen Hondas for the AMA 1967 racing season.

Early this year the factory agreed to do some research on modifying standard parts on an experimental basis for assembly by American Honda and Bob Hansen. The task must have been a large one for the engineers; they have never before worked on cylinders larger than 125cc displacement for motorcycle racing, not to mention only two valves per cylinder.

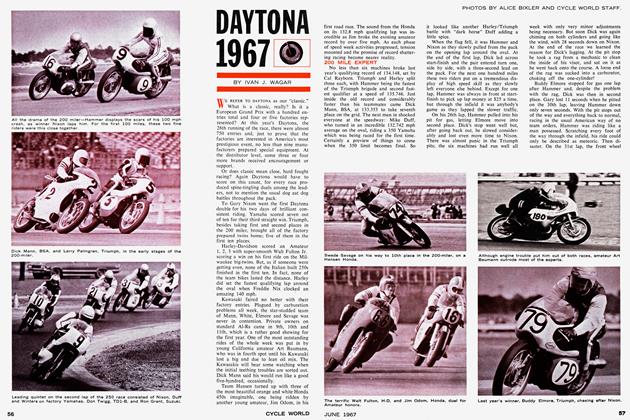

Factory parts would be a tremendous boon to the dealers and individuals who have made attempts to convert CB450s for racing, often at very large expense, and without much real success. The fastest nonHansen Honda 450 at Daytona was entered by Norm Reeves of Paramount, California. Ridden by Emory McKeen, it qualified in 56th place at 120 mph, more than 10 mph down on the Hansen machines. (An ignition fault kept Savage down to 128.6 in time trials, but he was back up to 132 mph in the race.)

To get a closer look at one of these beauties, we took Swede Savage's Daytona machine to Riverside. As mentioned in the Daytona race report, Swede rode the last half of the race with no rear brake and almost the whole race without a tachometer, and still managed a very creditable 10th place, with teammate Larry Schaffer 12th. An extremely good showing for the first time at Daytona.

Before going to Riverside, the tachometer cable was hooked up and a new rear brake pedal fitted. Other than a light cleaning, the machine was just as it had finished the tortuous 200 mile race.

Although basically CB450 in most respects, the racing version does have many items not found on the road-going model. Several special or modified parts are from the now outdated CR project. These include: the four leading shoe 8-inch front brake and single drum, two leading shoe, 7-inch rear; front fender, seat, six-gallon aluminum gas tank, clip-on bars and levers. The front forks are from the CL series scramblers with the internal dampers altered for road racing. The rear dampers are the take-apart type and have been modified.

The frame has been extensively changed at the rear with two gusseted members in place of the standard single, middle down tube. Cross bracing above the swing arm pivot further strengthens the main cradle and the swing arm is gusseted for almost its full length.

Wheelbase remains the same at 53 inches and all other dimensions are exactly the same as a standard CB450, including steering head angle. A CL series hydraulic steering damper has been fitted, in addition to the adjustable friction disc standard unit. Both fork crowns are CB450, but have been reinforced. On the upper crown this strengthening is accomplished by using a separate external bridge of about 1/8inch thickness.

The fairing is fabulous. Made in fiberglass, it bears a striking resemblance to the one used on the 500 four-cylinder. Small oil radiator ducts to maintain 100 to 110°C oil temperature are molded into the leading edge of the sides just above the exhaust pipes. AMA rules call for five fairing mounting points, but the CB 450, like the GP racers, has an abundance — nine.

(Continued on following page)

Surprisingly little has been done to the engine, considering the way it performs. Many "experts" have theorized that Honda's torsion bar valve gear would not stand up to the stress imposed by long distance road racing, especially at the rpm required to achieve high power output. There is ample space in the cam boxes to fit valve springs, but Hansen felt the torsion bars were up to the task, and he was right. Swede's engine not only ran practice and the race at 11,000 rpm redline, it also withstood the fantastic overrevving of changing down prematurely after he lost the rear brake. When we rode the machine at Riverside, there was still no indication of valve float at redline.

The compression ratio has been increased to 9.2:1 from the original 8.5; not much of an increase for serious racing, but Honda has never used really high compression figures in their racing machines. Instead, they concentrate on maximum mixture volume through the engine in a given period of time. Or, put differently, ultimate breathing is the first consideration, even if it means a lower compression ratio than that possible in any given design. There is a large reliability gain in not using the maximum compression available, due to larger valve to piston clearance, and this is one of the reasons why racing Hondas are almost indestructible.

Another component with which Honda does not go to the extreme is the camshaft. It was obvious in the first few minutes of operation that, like other Honda racers, the cam timing is actually quite mild. In the case of the fours, the twist grip was more like a rheostat controlling an electric motor; the rider simply dialed in more power with complete predictability. The CB 450 engine is not much different in this respect, for there is no point where the engine suddenly bursts into life. Although things really start to happen at 8,000 rpm, the progress is smooth and continuous.

A new primary drive housing was cast with inlet and outlet fittings for the oil rad hoses. Also, there is a plug in the center of the clutch housing bulge, which can be removed for clutch adjustments. In order that the engine may be easily checked with a timing light, the left side engine cover has a transparent housing to expose the magneto. It is interesting to note that the timing has been retarded 5° and is now 40° btdc.

Honda CR crankcases are vented to atmosphere; that is, they do not have timed engine breathers to maintain a given crankcase pressure. Usually there is an oil collector tower on top of the gearbox behind the cylinders, and from it a plastic tube runs to the back of the machine to exhaust oil vapor. The tower is a simple device with staggered baffles to stop oil from being blown out in large quantities. In the CB 450 there is an additional chamber in the breather line called an oil condenser, and it converts the vapor back to liquid and returns the oil to the pump. Not only does this conserve the oil supply, but it also means less oil on the track.

Riding the CB 450 is a rare pleasure. Everything is tailored for rider comfort, even to the flush mounted chin pad. The screen is higher than on most current road racing machines and, though some streamlining is sacrificed, it further enhances comfort. The engine is reluctant to start when cold, typical of CR models, but once warmed up, it will light right off. Much of this can be attributed to the large 35mm Keihin racing carburetors, the most expensive mods to the machine. Tractability is probably where the engine excels the most. Almost no clutch slip is required to get the machine underway, and through the gears there is a silky smoothness about the engine and transmission. Most surprising was the almost complete lack of vibration throughout the entire operating range.

The clutch, although properly adjusted, would not release completely when the lever was all the way in, and a dragging clutch is a good way to miss downshifts, so shut off points were a bit earlier than normal. Running Daytona gearing at Riverside also meant it was possible to arrive everywhere a little faster than what is considered comfortable. But the very effective brakes impart confidence almost immediately. Predictable and progressive, they can be used while banked well over without feeling dangerous.

The rear suspension could do with a little more damping for the rather large bumps through turn one, but the dampers can be modified to suit individual taste. Swede Savage is slightly heavier than our test rider and probably used more stroke, thereby getting more damping effect.

Although the 450 engine is tall, with considerable weight up high due to the overhead cam drive, the handling is light and positive. This was especially noticeable through Riverside's fast esses, where it is necessary to flick the machine hard from peg to peg.

With a total dry weight of only 312 pounds, the CB 450 is only slightly heavier than the famous British production racers, but the engine is a good deal more flexible and easier to use. We certainly hope to see more of this project, particularly if Honda can be talked into making parts available to their dealers. ■