CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

A Taste of Hot Saki

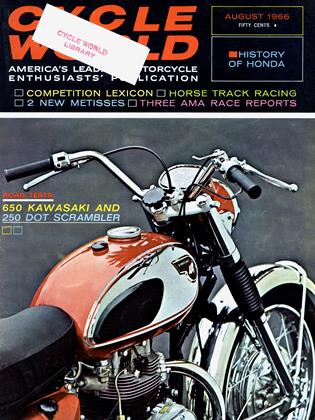

THERE IS THE TEMPTATION, when one makes a first acquaintance with Kawasaki’s new 650cc tourer, to dismiss the bike as a mere copy of a certain now-superseded, British forty-inch twin. A resemblance exists, to be sure, but it is largely superficial. Taken as a whole, and in virtually all particulars, the Kawasaki model 650-W1 is not a copy of anything.

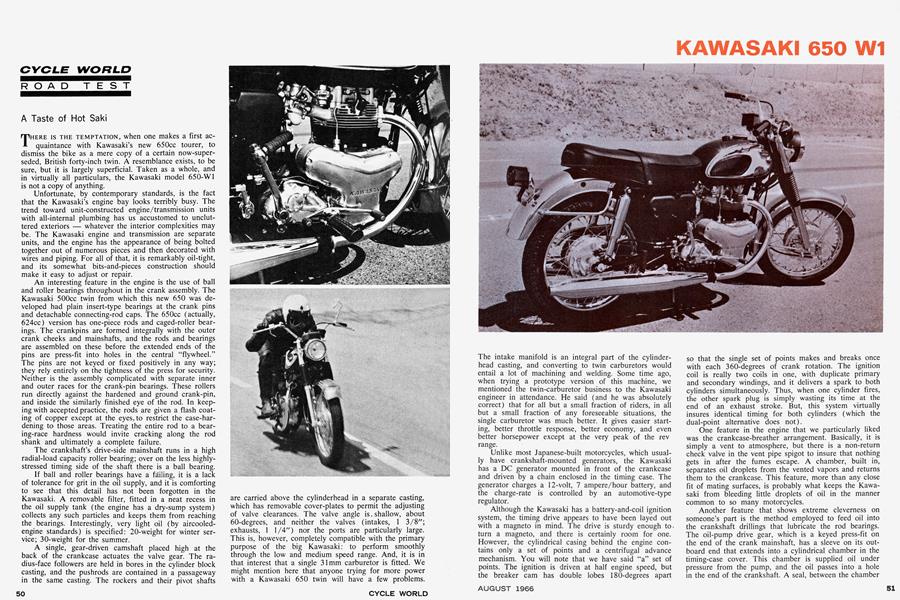

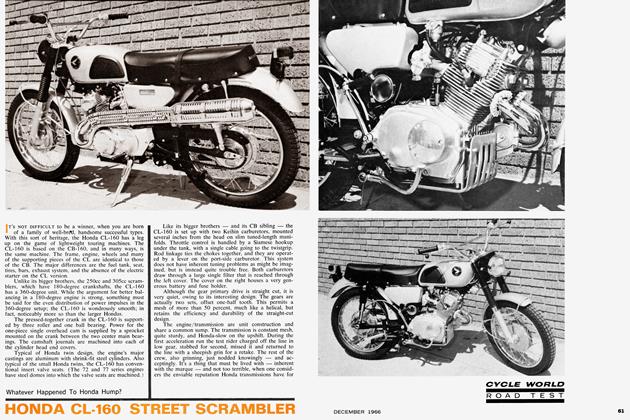

Unfortunate, by contemporary standards, is the fact that the Kawasaki’s engine bay looks terribly busy. The trend toward unit-constructed engine/transmission units with all-internal plumbing has us accustomed to uncluttered exteriors — whatever the interior complexities may be. The Kawasaki engine and transmission are separate units, and the engine has the appearance of being bolted together out of numerous pieces and then decorated with wires and piping. For all of that, it is remarkably oil-tight, and its somewhat bits-and-pieces construction should make it easy to adjust or repair.

An interesting feature in the engine is the use of ball and roller bearings throughout in the crank assembly. The Kawasaki 500cc twin from which this new 650 was developed had plain insert-type bearings at the crank pins and detachable connecting-rod caps. The 650cc (actually, 624cc) version has one-piece rods and caged-roller bearings. The crankpins are formed integrally with the outer crank cheeks and mainshafts, and the rods and bearings are assembled on these before the extended ends of the pins are press-fit into holes in the central “flywheel.” The pins are not keyed or fixed positively in any way; they rely entirely on the tightness of the press for security. Neither is the assembly complicated with separate inner and outer races for the crank-pin bearings. These rollers run directly against the hardened and ground crank-pin, and inside the similarly finished eye of the rod. In keeping with accepted practice, the rods are given a flash coating of copper except at the eyes, to restrict the case-hardening to those areas. Treating the entire rod to a bearing-race hardness would invite cracking along the rod shank and ultimately a complete failure.

The crankshaft’s drive-side mainshaft runs in a high radial-load capacity roller bearing; over on the less highlystressed timing side of the shaft there is a ball bearing.

If ball and roller bearings have a failing, it is a lack of tolerance for grit in the oil supply, and it is comforting to see that this detail has not been forgotten in the Kawasaki. A removable filter, fitted in a neat recess in the oil supply tank (the engine has a dry-sump system) collects any such particles and keeps them from reaching the bearings. Interestingly, very light oil (by aircooledengine standards) is specified: 20-weight for winter service; 30-weight for the summer.

A single, gear-driven camshaft placed high at the back of the crankcase actuates the valve gear. The radius-face followers are held in bores in the cylinder block casting, and the pushrods are contained in a passageway in the same casting. The rockers and their pivot shafts are carried above the cylinderhead in a separate casting, which has removable cover-plates to permit the adjusting of valve clearances. The valve angle is. shallow, about 60-degrees, and neither the valves (intakes, 1 3/8"; exhausts, 1 1/4") nor the ports are particularly large. This is, however, completely compatible with the primary purpose of the big Kawasaki: to perform smoothly through the low and medium speed range. And, it is in that interest that a single 31mm carburetor is fitted. We might mention here that anyone trying for more power with a Kawasaki 650 twin will have a few problems. The intake manifold is an integral part of the cylinderhead casting, and converting to twin carburetors would entail a lot of machining and welding. Some time ago, when trying a prototype version of this machine, we mentioned the twin-carburetor business to the Kawasaki engineer in attendance. He said (and he was absolutely correct) that for all but a small fraction of riders, in all but a small fraction of any foreseeable situations, the single carburetor was much better. It gives easier starting, better throttle response, better economy, and even better horsepower except at the very peak of the rev range.

KAWASAKI 650 W1

Unlike most Japanese-built motorcycles, which usually have crankshaft-mounted generators, the Kawasaki has a DC generator mounted in front of the crankcase and driven by a chain enclosed in the timing case. The generator charges a 12-volt, 7 ampere/hour battery, and the charge-rate is controlled by an automotive-type regulator.

Although the Kawasaki has a battery-and-coil ignition system, the timing drive appears to have been layed out with a magneto in mind. The drive is sturdy enough toturn a magneto, and there is certainly room for one. However, the cylindrical casing behind the engine contains only a set of points and a centrifugal advance mechanism. You will note that we have said “a” set of points. The ignition is driven at half engine speed, but the breaker cam has double lobes 180-degrees apart so that the single set of points makes and breaks once with each 360-degrees of crank rotation. The ignition coil is really two coils in one, with duplicate primary and secondary windings, and it delivers a spark to both cylinders simultaneously. Thus, when one cylinder fires, the other spark plug is simply wasting its time at the end of an exhaust stroke. But, this system virtually insures identical timing for both cylinders (which the dual-point alternative does not).

One feature in the engine that we particularly liked was the crankcase-breather arrangement. Basically, it is simply a vent to atmosphere, but there is a non-return check valve in the vent pipe spigot to insure that nothing gets in after the fumes escape. A chamber, built in, separates oil droplets from the vented vapors and returns them to the crankcase. This feature, more than any close fit of mating surfaces, is probably what keeps the Kawasaki from bleeding little droplets of oil in the manner common to so many motorcycles.

Another feature that shows extreme cleverness on someone’s part is the method employed to feed oil into the crankshaft drillings that lubricate the rod bearings. The oil-pump drive gear, which is a keyed press-fit on the end of the crank mainshaft, has a sleeve on its outboard end that extends into a cylindrical chamber in the timing-case cover. This chamber is supplied oil under pressure from the pump, and the oil passes into a hole in the end of the crankshaft. A seal, between the chamber and the rotating crankshaft, is provided by a “piston-ring” running in a groove in the pump drive-gear sleeve. There is enough clearance, between the sleeve and the oilchamber bore, to prevent any contact through crank flexing, and the ring (which is free-floating in its groove) fills the gap. Of course, there is some leakage, but the bulk of the oil will be pumped into the crankshaft’s oilways. A much better arrangement, it seems to us, than a plain bushing (which wears rapidly if there is crank flexing) or a rubber garter-type seal (which is liable to blow-out from excess oil pressure if too many revs are applied on a cold morning).

Of the transmission, we can only say that it is not up to the standard of the engine. The ratios are properly staged, and it is not noisy, and it is probably sufficient in terms of reliability. But, it is not at all satisfactory from the standpoint of gearchange smoothness and precision. All of this might well be caused by a dragging clutch, but as it was characteristic of two examples we rode, we must consider it more or less typical of the type. A part of this unpleasantness was compensated by the Kawasaki’s shift sequence, which runs neutral, 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th. With neutral all the way “up,” that bothersome business of fishing for it between 1st and 2nd is eliminated — and good riddance. Would that all others had arranged things the same way.

All of this machinery is cradled in quite a nice “duplex” frame, with a typical suspension system of oil-damped spring-struts and a swing arm for the rear wheel, and oil-damped telescopic forks up front. The system provides a good ride, and very light and agile low-speed handling. In all but father slow turns, there is a lack of tracking precision that we would attribute to insufficient damping at the rear. Possibly, the chaps at the Kawasaki factory have noticed this, too, for the bike is fitted with not only the customary friction-disc damper, it also has a hydraulic strut-type damper between the frame and the right side of the lower fork bridge.

The Kawasaki’s brakes are great. It has typicallyJapanese aluminum-alloy drums, with iron liners, and dual leading-shoes at the front wheel. Very little pressure is required at the controls to get a lot of action at the wheels. At the same time, the brakes are not too fierce; a complete incompetent could lock things up and go on his head, but that is true of any bike having enough braking power to meet any situation.

Sheer, blinding speed is not one of the Kawasaki’s attributes. It gets down the road at a respectable rate, with a top just over 100 mph and a speed at the end of a standing-start 1 /4-mile of 85 mph, but there are obviously faster 650 twins. However, it is right in there with those having single carburetors and mild valve timing. Our tests were performed with what was actually not enough miles on the bike for it to show to best advantage, but there would probably be only a fractional improvement with more break-in time. Not enough change to worry about.

What the Kawasaki does well is medium-speed cruising. The bike is very smooth, and cruises along at 70 mph as though it would continue forever. Starting is extremely easy, hot or cold, and it will pull along in traffic without any of the stuttering and stumbling that is characteristic of the “performance-above-all” motorcycle. Hardly surprising, if you consider that this 650 is a direct development from a 500 that Kawasaki builds primarily for police use in Japan.

Some work remains to be done with adjusting the position of handlebars relative to the seat/relative to the footpegs, which would make the bike more comfortable for the oversize occidental, but the Kawasaki is not actually uncomfortable in its present form. In fact, riders of medium to small stature would probably prefer it “as-is.” We all liked the overall finish. The Kawasaki impressed us as being made with more than the usual care, and there was enough chrome and polished alloy to satisfy anyone. On balance, a very good motorcycle.

KAWASAKI 650-W1

$1195