NSU HISTORY

A Story of Precision and Speed

GEOFFREY WOOD

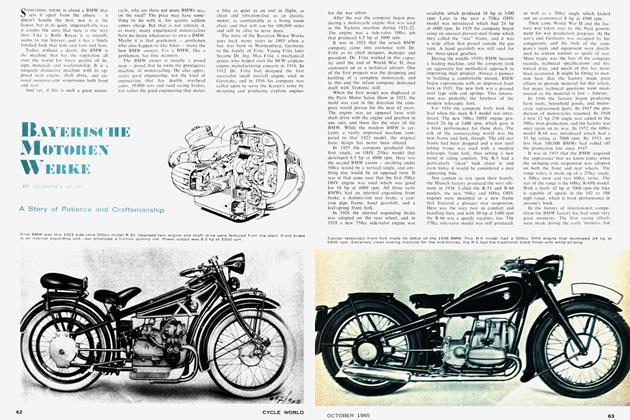

SAWDUST, PLASTER OF PARIS, and sewing machines may not seem to have much to do with the motorcycle industry, but nevertheless these commodities had a great deal to do with the early days of the German NSU concern. The story began way back in 1873, when two engineers, Christian Schmidt and Heinrich Stoll, joined forces to manufacture and repair sewing and knitting machines.

On a small island in the Danube River by a little town named Riedlingen, they set up shop with an old English-made lathe and a waterwheel to provide the power. The little business produced a good Strickmaschinen for the local Hausfrau, and the company prospered to such an extent that a move was made in 1874 to a larger factory at Reutlingen. Here, the partners parted company, Heinrich remaining with the original sewing machine and Christian going on to Neckarsulm. Schmidt located an old plaster of Paris mill, which had also been a sawmill, and here he settled down to produce his own sewing machine.

Schmidt had another goal, however, and this was to produce a bicycle, as the two-wheeled craze was sweeping the country. Christian never lived to see his dream come true, for he died just four years later, after getting his NSU concern on its financial feet. It was then left to his brother-in-law, Gottlob Banzhaf, to bring out the new NSU bicycle in 1886. Schmidt had another goal, however, and this was to produce a bicycle, as the two-wheeled craze was sweeping the country. Christian never lived to see his dream come true, for he died just four years later, after getting his NSU concern on its financial feet. It was then left to his brother-in-law, Gottlob Banzhaf, to bring out the new NSU bicycle in 1886.

The following years, Gottlob got the factory humming and the NSU bicycles and parts sold abundantly. About the turn of the century, there was much excitement over the internal combustion engine being applied to transportation, and Banzhaf was caught up in the fever. Already in the bicycle business, it was only natural that he would have a bash at producing a motorbike. This he did in 1900 by attaching a Swiss-made 1-3/4 hp engine to his bicycle. Altogether, about 100 of these crude motorbikes were produced. The following years, Gottlob got the factory humming and the NSU bicycles and parts sold abundantly. About the turn of the century, there was much excitement over the internal combustion engine being applied to transportation, and Banzhaf was caught up in the fever. Already in the bicycle business, it was only natural that he would have a bash at producing a motorbike. This he did in 1900 by attaching a Swiss-made 1-3/4 hp engine to his bicycle. Altogether, about 100 of these crude motorbikes were produced.

The improvement of their product began immediately, and in 1902 a heavier frame was adopted to cope with horsepower instead of human muscle power, and a spray-type carburetor replaced the earlier drip feed unit. Another NSU first in that early year was a reliable magneto ignition, a device which enabled an NSU to cover the surprising mileage of 1,600 miles without a breakdown. The improvement of their product began immediately, and in 1902 a heavier frame was adopted to cope with horsepower instead of human muscle power, and a spray-type carburetor replaced the earlier drip feed unit. Another NSU first in that early year was a reliable magneto ignition, a device which enabled an NSU to cover the surprising mileage of 1,600 miles without a breakdown.

In 1903, the company produced an all NSU machine, with a 2 hp engine designed by Christian Schmidt's son, Karl. The new model proved reliable and production soared to 2,228. This model was followed in 1905 by a water-cooled 4 hp NSU, and then some V-twins of 3, 3½, 5 and 5½ horsepower. Sales expanded and so did the factory. In 1903, the company produced an all NSU machine, with a 2 hp engine designed by Christian Schmidt’s son, Karl. The new model proved reliable and production soared to 2,228. This model was followed in 1905 by a water-cooled 4 hp NSU, and then some V-twins of 3, VA, 5 and 5lA horsepower. Sales expanded and so did the factory.

The next innovations of note were the trailing link front fork in 1905, which gave a much softer ride than the previous rigid forks; then a telescopic spring dampened leading link fork in 1906; and lastly, a two-speed engine hub assembly that provided a gear for both hills and level road. In 1906, the company also entered the "light" car field with threeand fourwheel vehicles of 10 and 24 hp. The next innovations of note were the trailing link front fork in 1905, which gave a much softer ride than the previous rigid forks; then a telescopic spring dampened leading link fork in 1906; and lastly, a two-speed engine hub assembly that provided a gear for both hills and level road. In 1906, the company also entered the “light” car field with threeand fourwheel vehicles of 10 and 24 hp.

In 1907, the first Isle of Man TT race was held, and the factory sent Martin Geiger over to uphold homeland honors, as the British were good customers of NSU motorbikes. Geiger had a troublefree run that day and finished in fifth position - NSU's first racing success. The following year the concern sold its first production racing machine, a rigid forked lightweight model with an astounding 1½ hp to propel it! In 1907, the first Isle of Man TT race was held, and the factory sent Martin Geiger over to uphold homeland honors, as the British were good customers of NSU motorbikes. Geiger had a troublefree run that day and finished in fifth position — NSU’s first racing success. The following year the concern sold its first production racing machine, a rigid forked lightweight model with an astounding 1 lA hp to propel it!

In 1908, the factory also brought out some V-twin engines of 2½ hp on up to 7½ hp. On one of the larger jobs a fellow by the name of Liese recorded a speed of 108.5 mph (68 mph) which was claimed to be a world record for its day, although no official records were kept in those early days of the sport. The following year Otto Lingenfelders clocked his NSU at 124 kph (77.5 mph) on a road near Los Angeles, California, and the NSU In 1908, the factory also brought out some V-twin engines of 2Vi hp on up to 1XA hp. On one of the larger jobs a fellow by the name of Liese recorded a speed of 108.5 mph (68 mph) which was claimed to be a world record for its day, although no official records were kept in those early days of the sport. The following year Otto Lingenfelders clocked his NSU at 124 kph (77.5 mph) on a road near Los Angeles, California, and the NSU folks once again claimed the title of world’s fastest.

With an expanding export business, the factory was encouraged, and they listed a 4 hp single in 1909 with a bore and stroke of 82 x 105mm. A two-speed rear hub was used which contained an internal expanding brake. This brake deserves particular note, as the British did not generally adopt this method of stopping until the middle 1920s.

With a continued expansion of export sales, the NSU factory proceeded to introduce many new models with fine engineering achievements. In 1911, a method of rear suspension was produced, and a 6 hp V-twin had all chain drive with a three-speed gearbox and plate clutch. For 1912 the pushrod and rocker type of overhead valve engine was introduced, a truly great milestone in European engineering history. Then, in 1914, the “ultimate” NSU was available with a powerful l,000cc 9 hp engine that provided speeds to 60 mph and with a total weight of only 300 lbs.

Then came the Kaiser’s war and the NSU factory was converted to military production. During the war the factory produced a \Vi hp lightweight called the “Pony,” and this model formed the basis of a 2 hp utility mount after the war. The effect of war on NSU was extensive, and it was not until 1922 that the factory really got back on its feet again when 3,000 people were employed. The models produced were basically the pre-war machines until 1924, when a completely new “unit-construction” line came off the drawing boards. The first model was a 2 hp side-valve single that was available with either a two or three speed gearbox and belt drive. A four hp twin was next, and then an 8 hp twin, and these sleek speedsters had all-chain drive.

Aiming for the utility market, the Kriegspony was next produced, and this inexpensive lightweight featured such niceties as a clutch, a weight of only 160 lbs., a top speed of 38 mph, and a gas mileage of over 100 mpg. In 1929, the company pioneered “line” production in their factory, and the sales once again began an expansion. Walter Moore also joined NSU that year, and this Englishman is the man who designed the original overhead camshaft racing Norton. Was this a hint of things to come from NSU?

The answer was not long in coming, and almost overnight the NSU folks were “smack dab” in the middle of the racing game. The first racing model off Moore’s drawing boards was the overhead-cam single, produced in 350, 500, 600 and 700cc sizes. The new racer was a cobby looking model, with a single cam actuating a pair of rockers. Hairpin valvesprings were used for valve control, and the Amal racing carburetor had a slight downdraft angle. The cam drive was by a vertical shaft and bevel gears, and ignition was by a Bosch magneto.

The engine was mounted in a singleloop cradle frame, and the girder fork at the front was the only method of suspension. A footshift gearbox was used, and the brakes were husky units with aluminum alloy hubs. The wrap-around oil tank was similar to that used on the British Nortons, and the long fuel tank was hand-hammered aluminum alloy.

The works racing team consisted of Britisher Tommy Bullus and German Heiner Fleischmann. The new NSU racer proved to be fast, but not quite fast enough to challenge the top British marques. About the only really significant success attained was by Bullus in the 1930 Grand Prix of Italy, where he scored a surprising victory.

Then followed the worldwide economic depression, and this catastrophe hurt Germany more than most other countries. Always practical, NSU turned their efforts from playing with expensive racing machines to producing a cheap utility motorbike. The first was the 63cc Motosulm, which might be considered to be the ancestor of today’s Quickly model. The little two-stroke engine was mounted on the front fork and it drove the front wheel through a clutch and chain. Car production ceased at NSU and the full plant facilities were turned to producing this popular little motorbike.

The next new NSU was a Walter Moore designed moped in 1936. This little jewel, named the “Quick,” sold no less than 235,000 units. As Germany recovered from the depression, it was only natural that larger, more expensive models would be produced, and so during 1935 and 1936 the range of NSUs that were produced rapidly expanded. One of the most popular models was the ZDB, a 200cc two-stroke of unfailing reliability. The ZDB produced a healthy 7 hp for a 53 mph top speed. The little two-stroke had a rigid frame and girder front fork.

The next, more expensive NSUs were the 350 and 500cc Tourensport models. These sportsters had single-cylinder ohv engines with a bore and stroke of 75 x 79mm on the 350 and 80 x 99mm on the 500. The horsepower was 18 and 22 on the two models, developed at 5,200 rpm on a 6 to I compression ratio. The gear ratios for the 350 model were 15.4, 10.2, 6.9, and 5.8 to 1; and on the 500 model they were 13.2, 8.8, 5.9, and 4.95 to 1. Gear shifting was done by hand; this was common practice on the European continent in the middle 1930s.

Then, for the sidecar enthusiast, there was the big 600cc side-valve model which produced a beefy 16 hp with lots of low speed torque. There also was available a 500cc model which developed 12.5 hp. The bore and stroke of the larger motor were 87.5 x 99mm and the 500 had the same measurements as the ohv version.

In 1938, the range was expanded to include a brutishly powerful 600cc ohv model, which developed 24 hp on a 6 to 1 compression ratio. The big 600 still had no method of rear suspension, though, and the girder fork was retained at the front. As with the other NSU models, the engine and gearbox were in one unit case, making for a clean looking design.

It was during the mid-1930s that NSU again became interested in racing, probably because it was the first time since the depression that they could afford to participate. Their old single was sadly lacking in speed, compared to the allconquering Nortons and Velocettes, and so a new engine was produced. During 1937, a double-overhead-cam single was raced by Heiner Fleischmann, which was actually just the older engine with a twin cam head and other improvements. The single proved to be too slow to have any chance at victory, and so a new design was thought up.

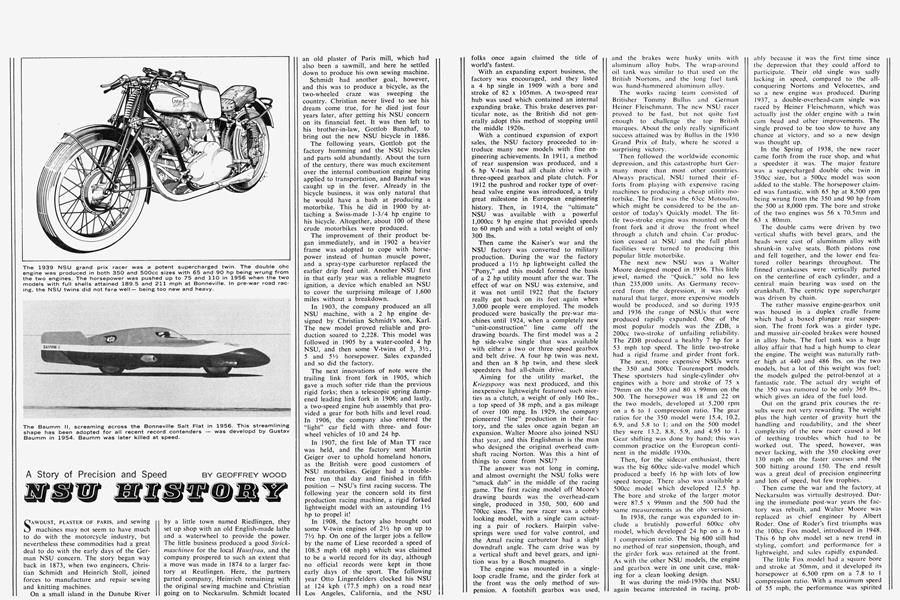

In the Spring of 1938, the new racer came forth from the race shop, and what a speedster it was. The major feature was a supercharged double ohc twin in 350cc size, but a 500cc model was soon added to the stable. The horsepower claimed was fantastic, with 65 hp at 8,500 rpm being wrung from the 350 and 90 hp from the 500 at 8,000 rpm. The bore and stroke of the two engines was 56 x 70.5mm and 63 x 80mm.

The double cams were driven by two vertical shafts with bevel gears, and the heads were cast of aluminum alloy with shrunk-in valve seats. Both pistons rose and fell together, and the lower end featured roller bearings throughout. The finned crankcases were vertically parted on the centerline of each cylinder, and a central main bearing was used on the crankshaft. The centric type supercharger was driven by chain.

The rather massive engine-gearbox unit was housed in a duplex cradle frame which had a boxed plunger rear suspension. The front fork was a girder type, and massive air-cooled brakes were housed in alloy hubs. The fuel tank was a huge alloy affair that had a high hump to clear the engine. The weight was naturally rather high at 440 and 486 lbs. on the two models, but a lot of this weight was fuel; the models gulped the petrol-benzol at a fantastic rate. The actual dry weight of the 350 was rumored to be only 369 lbs., which gives an idea of the fuel load.

Out on the grand prix courses the results were not very rewarding. The weight plus the high center of gravity hurt the handling and roadability, and the sheer complexity of the new racer caused a lot of teething troubles which had to be worked out. The speed, however, was never lacking, with the 350 clocking over 130 mph on the faster courses and the 500 hitting around 150. The end result was a great deal of precision engineering and lots of speed, but few trophies.

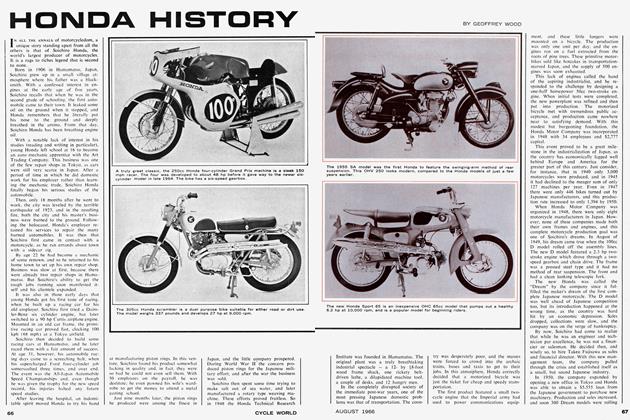

Then came the war and the factory^at Neckarsulm was virtually destroyed. During the immediate post-war years the factory was rebuilt, and Walter Moore was replaced as chief engineer by Albert Roder. One of Roder’s first triumphs was the lOOcc Fox model, introduced in 1948. This 6 hp ohv model set a new trend in styling, comfort and performance for a lightweight, and sales rapidly expanded.

The little Fox model had a square bore and stroke at 50mm, and it developed its horsepower at 6,500 rpm on a 7.8 to 1 compression ratio. With a maximum speed of 55 mph, the performance was spirited enough to capture the hearts of the public, yet the price was low enough for the wartorn Europeans to afford. A leading link front fork and a torsion-arm rear suspension made the Fox a comfortable mount.

The rigid frame 125cc ZDB two-stroke remained in production as a cheap utility bike, and the 200cc LUX model was also added to the range. The policy at NSU was to produce small bikes that the poor populace could afford, and any racing would have to be on a very slim budget.

Racing runs deep in the German blood, however, and history records the deeds of a fellow by the name of Wilhelm Herz. Wilhelm built up a 350cc racer from the ruins at the factory, and then later a 500cc model. At first he contented himself with competing only in German national races, as Germany was on “probation" by the FI M until 1951 and could not compete in international racing. Using his blown twins, he racked up a list of impressive home country victories, but the urge for something really big gnawed away inside.

Finally Herz could stand it no longer and he approached the company executives about his plan to capture the world motorcycle speed record. Surprisingly, the upper echelon agreed, and Herr Roder went to work to prepare the bikes. By fitting a vane-typfe blower instead of the original impeller unit, it was possible to increase the horsepower to 70 and 105 on the two engines. The next step was to design a fully streamlined shell to cover the bike and rider, and then everything was pronounced ready.

On April 12, 1951, the quiet dawn of the Munich-Ingolstadt Autobahn was shattered by the ripping roar of the 500cc supercharged twin. Wilhelm rode well that day, for the speed record took a thrashing. The new speed was 180.065 mph — NSU was in the news!

Meanwhile, Roder was not sitting still. Off his drawing boards came some new road racing designs and some roadsters. The most exciting of the roadsters was the 250cc Max, which featured a unique connecting rod and eccentrics method of driving the single overhead cam. Introduced in 1953, the Max has been followed by a 175cc version called the Maxi, and a refined 250cc version called the Super Max.

These ohc models are still produced today, and they feature a clean looking pressed-steel frame with a leading link front fork and a standard swinging-arm rear suspension. With top speeds of 68 and 80 mph, the two NSU cammers have proven to be smooth and comfortable.

The best brain child of chief engineer Roder has probably been the 50cc Quickly model, a two-stroke moped introduced in 1953. This has become NSU’s best seller, with as many as 95,000 units being sold in one year. The specifications of the Quickly include a bore and stroke of 40 X 39mm in its little engine, which is mounted in an “open” type of bicycle frame.

Then there were the 350 and 500cc Konsul models which were introduced in 1954 and produced for a few years. These ohc sport singles were designed as a high speed or “clubman” type of sports bike, and the 500 had a maximum speed of around 100 mph. A clean looking mount, the Konsul featured a telescopic front fork and a plunger rear suspension. The two models were known for their fine workmanship, but they failed to catch the public’s fancy and so they were later dropped from production.

Sales of NSU products continued to climb until, in 1955, a total of 342,583 machines were produced. Then twowheeled sales began to fall in Europe as the countries had recovered so fully that the populace could afford the luxury of an automobile. NSU responded by introducing the Prinz light car in 1958, with a 600cc engine which was virtually a doubleup of the Max design.

Since then, the NSU folks have gained a great deal of fame with their Prinz car and their new Wankel-engined Spyder car. The company still produces motorcycles, but cars are taking an ever increasing share of production, as the standard of living in Germany continues to rise. The present range of NSU motorcycles includes the Quickly, the Maxi, and the Super Max — all carrying forward the goal of reliable transportation for the man on the street.

This, however, is not the end of this story of NSU, for the really greatest chapter in the marque’s history was in the 1953 to 1956 era, when the company made a full-fledged attack on the world’s great racing courses. Albert Roder, in 1952, began this chapter, when he designed new 125cc and 250cc grand prix racers. It took a year to get all the bugs worked out of his new design and develop some championship riders, but when this was accomplished, there was no doubt whatsoever that Herr Roder and equipe were the finest racing technicians in the motorcycle business.

The new 125cc racer was a single with measurements of 58 x 47.3mm, and a vertical shaft drove the set of spur gears on the double overhead camshafts. The 250 was a twin, with slightly different measurements of 55.9 x 50.8mm. Both racers featured a six-speed gearbox, a swinging arm frame, and a leading link front fork.

The new NSUs were first raced late in 1952 and Werner Haas obtained a significant second place in the Monza Grand Prix. During the winter, the models were refined and a sleek dolphin shell made its debut. The hand-hammered aluminum streamlining gave a notable increase in speed and earned the factory the reputation for progressive thinking.

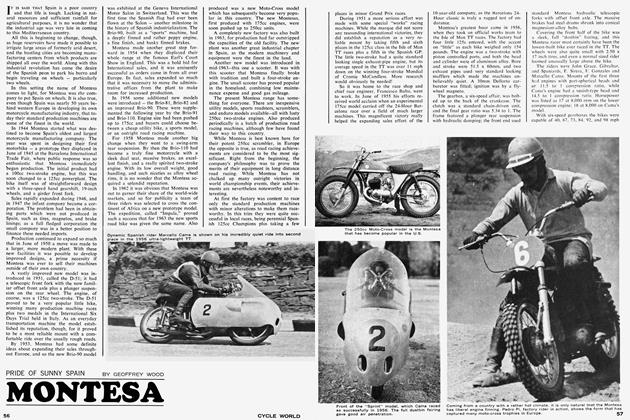

In the Isle of Man TT races, Werner rode both his racers into second place behind the 250 Guzzi and 125cc MV Agusta. In the Dutch event, the little Bavarian reversed the tables and from there he sped on to capture a first in the 250cc German classic, a second in the 125 event, a win in the 125cc Ulster event and a second in the 250 class behind teammate Reg Armstrong, and then another 250 second at Monza plus a win in the 125 class. This splendid record gave Werner both the 125cc and 250cc World Championships — the first-ever German Doppelweltmeister.

The 1953 successes were just a hint of things to come, for in the Spring of 1954, the NSUs were considerably quicker than the previous year. Development work by Roder during the winter had hoisted horsepower from 31 to 42 hp on the 250 model, and from 17 to 20 hp on the 125. With the dolphin fairing, Haas was clocked at 123 mph — which was a truly fantastic speed in those days.

In the June 250cc TT race Werner Haas, Rupert Hollaus, Reg Armstrong, H. P. Muller, and Hans Baltisberger took first, second, third, fourth, and six places to simply crush the opposition. Werner’s record speed was 90.88 mph, a truly remarkable increase over the 84.73 average of only one year earlier. In the 125cc class, Rupert Hollaus took the win, with Haltisberger in fourth position.

For the 1955 season the factory announced that they would retire from the pukka works team racing, but that H. P. Muller would ride a factory prepared 250cc Sportmax single in the classics The idea, no doubt, was to give some publicity to the new production racer, which was based on the standard Max model. Another factor may have been that the post-war economic boom was allowing the German citizenry to switch from motorcycles to cars, and NSU was beginning the switch to follow their new market.

At any rate, no one really gave Muller much chance at the world title that year. The season proved, however, to be full of surprises, mostly due to the lack of reliability on the part of the Italian factories, who were in the process of developing new engine designs. With a rather mediocre but reliable record, Muller garnered enough points by season’s end to capture the World Championship. The following few years the NSU Sportmax continued to acquit itself admirably, being the consistently best placed 250cc production racer until 1960, when better, more modern designs overwhelmed it. Two names, in particular, who established great reputations early in their careers on Sportmax models were John Surtees and Mike Hailwood.

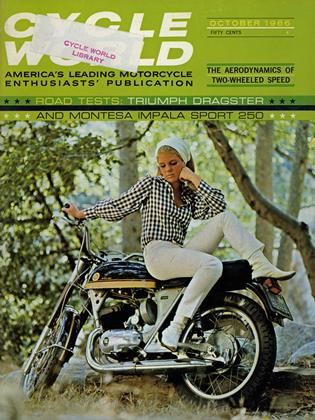

Then followed the swan song of the NSU concern in international competition — the fabulous 1956 speed records set at the Bonneville Salt Flat. Exhibiting the usual NSU type of technical excellence, the team arrived with a 12 hp supercharged 50cc model, a 15.5 hp unblown lOOcc model, the 20 hp 125cc and 42 hp 250cc unblown models (the 1954 works road racing engines), and the fabulous 75 and 110 hp 350 and 500cc models. The smaller engines were all mounted in the long and low “flying hammock” chassis developed by Gustav Baum, and the 350 and 500cc models were basically the prewar road racers with an elongated frame and a full shell.

For one whole week the NSU team screamed across the flat, and when it was over, no less than 54 new world records were put into the books. Probably the most noteworthy was the 210.64 mph clocking by Wilhelm Herz in the 500cc model — the first time the “double ton” had been exceeded on two wheels. The 350 model attained 189.5 mph, the 125 set a 150.3 mph record, the lOOcc unit clocked 138.0, and even the little 50cc projectile did 121.7 mph. The lOOcc and 250cc unsupercharged models ran on 80 octane gas, and the other engines used a diet of straight methanol. The runs, however, did have one big failure, and that was the 180 mph crash of Herz in the 250cc projectile when a gust of wind suddenly hit. It had been hoped that the 250 model might attain the magical 200 mph mark, but the model was too badly bent to make further attempts. Herz, miraculously, was unhurt in the crash.

The rest of the 1954 season was strictly an NSU walkover, except for the Monza classic, where the team did not race due to the death of Rupert Hollaus in a practice lap crash. Hollaus, however, had garnered sufficient points to become 125cc World Champion, with Haas again taking the 250 title. After the Ulster GP, the NSU dolphin fairing had been replaced with a full dustbin type and the improved air penetration provided a speed of 136 mph from the 250 twin — a truly remarkable achievement.

This is the story, then, of the NSU — one of the great prides of the Henenvolk. It is a story of typical Teutonic technical development and success. For the present the company is concentrating on their small cars instead of motorcycles, but maybe someday this will again change and we will hear the howl of NSU exhausts over the world’s great racing courses. ■