Cross country racing with a German twist.

JOHN G. YOUNG

HAVE YOU EVER entered a cross country race where your bike was disqualified for having tires or rims that weren't stock or if the taillight didn't work? Have you ever had to clamp down on the binders to avoid running down a group of people going to church? Have you ever competed against members of the armed forces, riding in uniform on government bikes, with the full blessing of both the race officials and the military?

Well my friend, if the answer to any of the above questions is no, then you never raced in a German cross country event. To fully understand how the European motorcycle enthusiast plays this "mayhem on wheels," you must first forget anything you have ever seen at your local track or races.

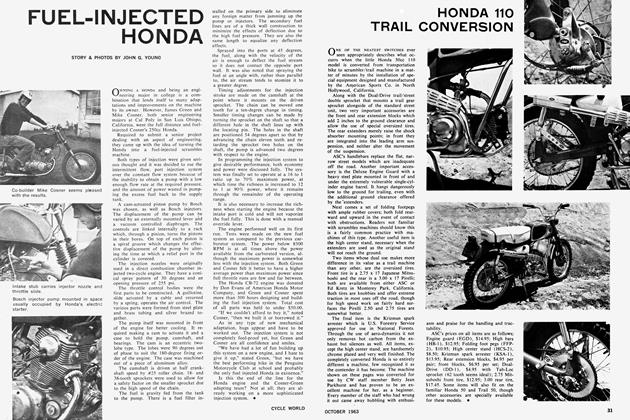

Earlier this Spring. 74 bikes entered an annual cross country event in the Southern section of Bavaria, West Germany at a town named Streitberg. From this enchanted ghost town the course looped its way through the famous villages of Oberfellendorf, Votgendorf, Wustenstein, Stegritz and Stornhof.

The course was roughly 20 miles in length, of which 18 miles were muddy hills, thick forests, swift streams and ample amounts of mud. The other two miles seemed to be carefully planned so as to disrupt, destroy and/or completely ruin any traffic pattern, church socials or any other activity that normally takes place on a Sunday morning. The race required each rider to complete seven laps within nine hours to have a chance of winning. When you multiply 74 wide-open throttles times seven laps, you have a giant sized dose of noise no matter how you swallow it.

The day before the race the local populace bolted their shutters, moved the livestock off the family pasture into safer areas, and set up beer and schnitzel stands along the course. On the morning of the race, before there was any indication of sunshine, bikes began arriving on trailers, inside automobiles and ridden into St rietberg. By seven o'clock every rider had paid his registration fee, sweated through the technical inspection, had his bike impounded and was sizing up the other competitors. For those who came to see the action, there were numerous debates on what tire pressure to use, what mixture of oil and gas was best, and the world wide debate on the superiority of two-strokes over four-strokes; or vice versa. Many fans just stared into the color packed impound area wishing they could afford to own one of the now silent sportsters. Many observers would have had to pay almost their complete earnings for a week to fill the fuel tanks of one or two machines.

Motorcycles are much cheaper in price on the German market than they are in the States, but even inexpensive by our standards they are way out of reach for the average German enthusiast. The German working man makes about one fourth the money of an American worker in the same field of work. An auto mechanic in California might make $100 a week, while a mechanic in Bamberg, Germany doing the same job and having the same skills would be lucky to make $100 a month.

Since owning a motorcycle with enough horsepower to move itself through the dirt is expensive, there were few if any of the shaggy black jacket group hanging around. Most of the riders were business and professional men who race purely for the sport and take a great amount of pride in their machines and their appearance. Many participants arrived in business suits and ties and only at the last minute did they don their racing togs.

The bikes were spotless and every one looked brand new. Not one was even dusty before the start, though many riders rode them half the night to enter. The first step was to register the bike with the racing commission. The registration fee was based on the displacement of the engine. The largest was for engines displacing over 250cc (about $10.00) and the lowest fee was $3.00 for engines displacing less than 50cc. The rider also had to prove to the commission that he was covered by adequate insurance, his bike was properly registered, and he held a valid driver's permit. It was interesting to note that there was no refund if any conditions were not met. The reasoning behind this was that if you don't want to play the game the way the rules say, then don't even bother to show up.

The next step was the technical inspection. Here the machine was gone over with a fine-toothed check list. The motor number had to match up with the registration, the tires and rims were checked and double checked to make sure they were the original ones when the bike was new, the lights, brakes, and mirrors had to be in perfect working order. If any item was not up to snuff, the machine was disqualified and that was that — no recourse. After each major component was inspected an official painted a small dot of paint on each part to assure that nothing would be switched before the race began. Actually there was no chance to even fill the tank as another official moved the bike to an impound area where it stayed until the start time.

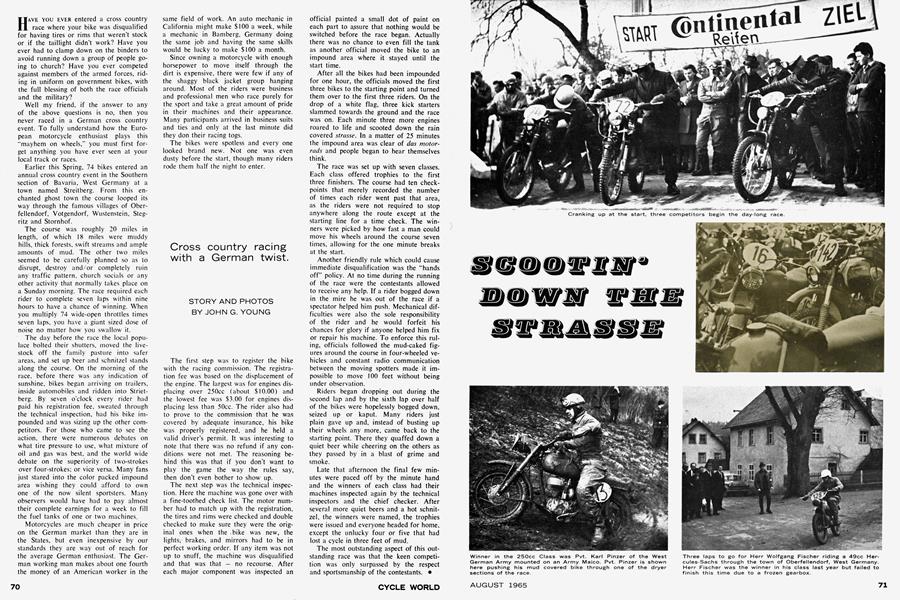

After all the bikes had been impounded for one hour, the officials moved the first three bikes to the starting point and turned them over to the first three riders. On the drop of a white flag, three kick starters slammed towards the ground and the race was on. Each minute three more engines roared to life and scooted down the rain covered strasse. In a matter of 25 minutes the impound area was clear of das motorrods and people began to hear themselves think.

The race was set up with seven classes. Each class offered trophies to the first three finishers. The course had ten checkpoints that merely recorded the number of times each rider went past that area, as the riders were not required to stop anywhere along the route except at the starting line for a time check. The winners were picked by how fast a man could move his wheels around the course seven times, allowing for the one minute breaks at the start.

Another friendly rule which could cause immediate disqualification was the "hands off" policy. At no time during the running of the race were the contestants allowed to receive any help. If a rider bogged down in the mire he was out of the race if a spectator helped him push. Mechanical difficulties were also the sole responsibility of the rider and he would forfeit his chances for glory if anyone helped him fix or repair his machine. To enforce this ruling, officials followed the mud-caked figures around the course in four-wheeled vehicles and constant radio communication between the moving spotters made it impossible to move 100 feet without being under observation.

Riders began dropping out during the second lap and by the sixth lap over half of the bikes were hopelessly bogged down, seized up or kaput. Many riders just plain gave up and, instead of busting up their wheels any more, came back to the starting point. There they quaffed down a quiet beer while cheering on the others as they passed by in a blast of grime and smoke.

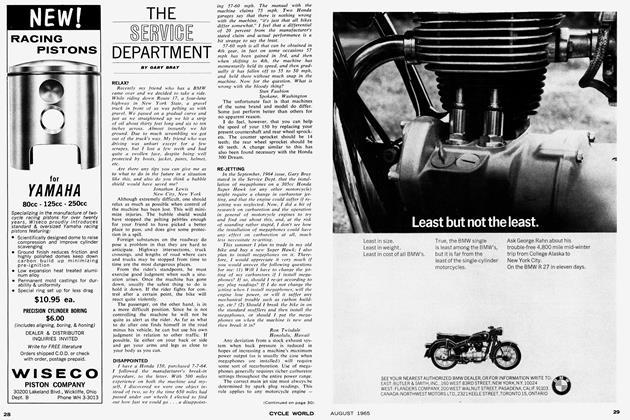

Late that afternoon the final few minutes were paced off by the minute hand and the winners of each class had their machines inspected again by the technical inspectors and the chief checker. After several more quiet beers and a hot schnitzel, the winners were named, the trophies were issued and everyone headed for home, except the unlucky four or five that had lost a cycle in three feet of mud.

The most outstanding aspect of this outstanding race was that the keen competition was only surpassed by the respect and sportsmanship of the contestants. •

SCOOTIN' DOWN THE STRASSE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue