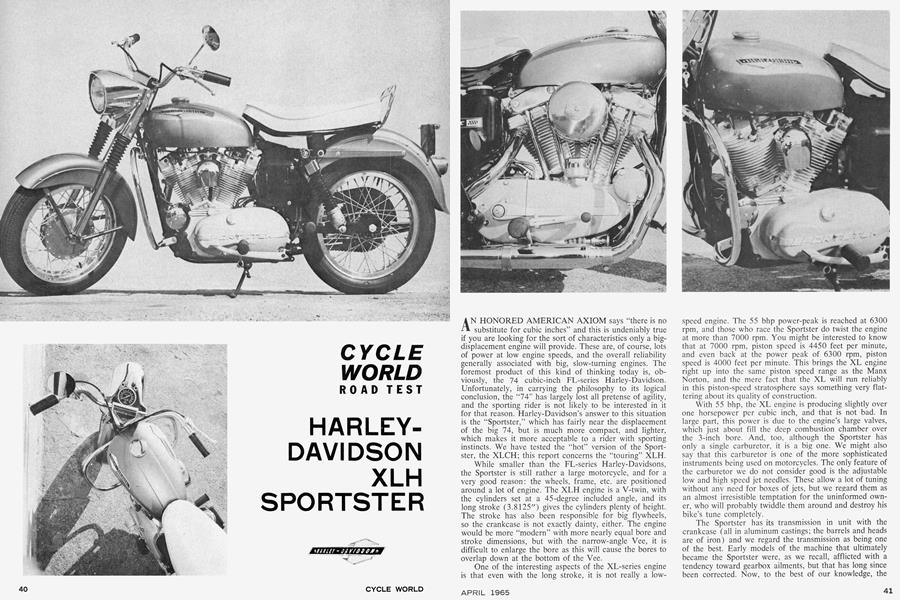

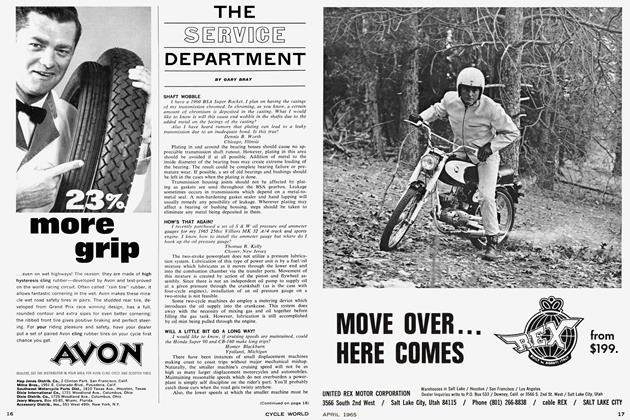

HARLEY-DAVIDSON XLH SPORTSTER

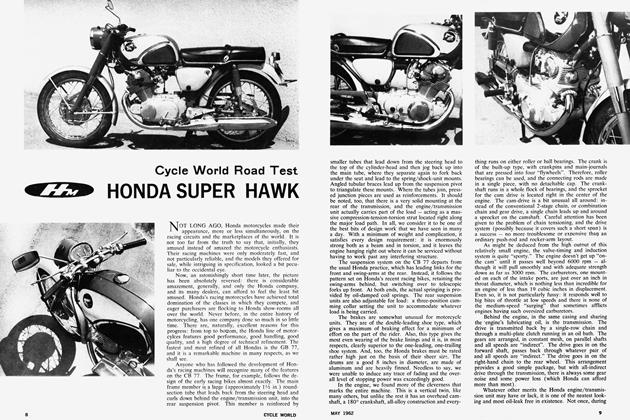

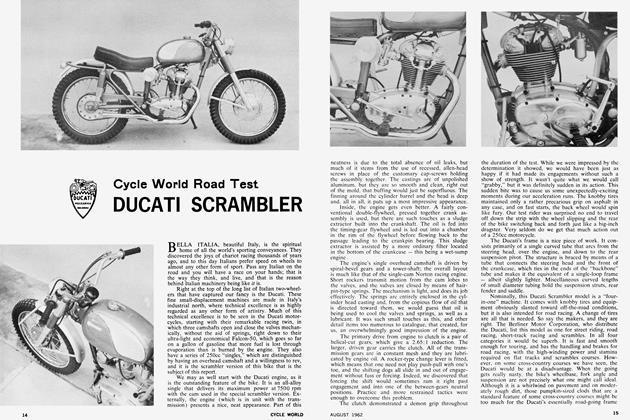

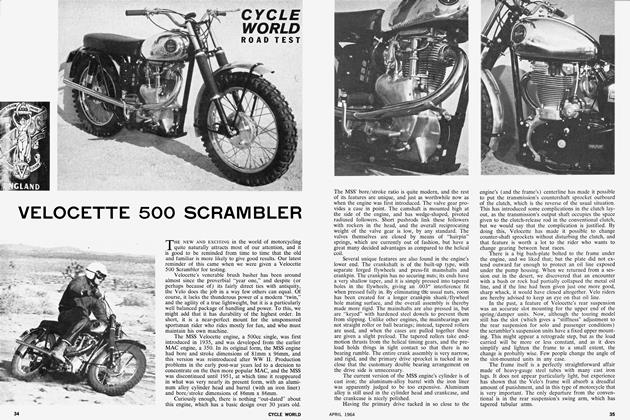

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

AN HONORED AMERICAN AXIOM says “there is no substitute for cubic inches” and this is undeniably true if you are looking for the sort of characteristics only a big-displacement engine will provide. These are, of course, lots of power at low engine speeds, and the overall reliability generally associated with big, slow-turning engines. The foremost product of this kind of thinking today is, obviously, the 74 cubic-inch FL-series Harley-Davidson. Unfortunately, in carrying the philosophy to its logical conclusion, the “74” has largely lost all pretense of agility, and the sporting rider is not likely to be interested in it for that reason. Harley-Davidson’s answer to this situation is the “Sportster,” which has fairly near the displacement of the big 74, but is much more compact, and lighter, which makes it more acceptable to a rider with sporting instincts. We have tested the “hot” version of the Sportster, the XLCH; this report concerns the “touring” XLH.

While smaller than the FL-series Harley-Davidsons, the Sportster is still rather a large motorcycle, and for a very good reason: the wheels, frame, etc. are positioned around a lot of engine. The XLH engine is a V-twin, with the cylinders set at a 45-degree included angle, and its long stroke (3.8125") gives the cylinders plenty of height. The stroke has also been responsible for big flywheels, so the crankcase is not exactly dainty, either. The engine would be more “modern” with more nearly equal bore and stroke dimensions, but with the narrow-angle Vee, it is difficult to enlarge the bore as this will cause the bores to overlap down at the bottom of the Vee.

One of the interesting aspects of the XL-series engine is that even with the long stroke, it is not really a lowspeed engine. The 55 bhp power-peak is reached at 6300 rpm, and those who race the Sportster do twist the engine at more than 7000 rpm. You might be interested to know that at 7000 rpm, piston speed is 4450 feet per minute, and even back at the power peak of 6300 rpm, piston speed is 4000 feet per minute. This brings the XL engine right up into the same piston speed range as the Manx Norton, and the mere fact that the XL will run reliably in this piston-speed stratosphere says something very flattering about its quality of construction.

With 55 bhp, the XL engine is producing slightly over one horsepower per cubic inch, and that is not bad. In large part, this power is due to the engine’s large valves, which just about fill the deep combustion chamber over the 3-inch bore. And, too, although the Sportster has only a single carburetor, it is a big one. We might also say that this carburetor is one of the more sophisticated instruments being used on motorcycles. The only feature of the carburetor we do not consider good is the adjustable low and high speed jet needles. These allow a lot of tuning without anv need for boxes of jets, but we regard them as an almost irresistible temptation for the uninformed owner, who will probably twiddle them around and destroy his bike’s tune completely.

The Sportster has its transmission in unit with the crankcase (all in aluminum castings; the barrels and heads are of iron) and we regard the transmission as being one of the best. Early models of the machine that ultimately became the Sportster were, as we recall, afflicted with a tendency toward gearbox ailments, but that has long since been corrected. Now, to the best of our knowledge, the Sportster has a nearly unbreakable transmission, and it shifts with remarkable precision and smoothness. “Neutral” is easily found, and very little pressure is required to snick from gear to gear, going up or down. It is, we will say again, a very good transmission; the unit in the FL-series Harley-Davidsons should be so good.

As we have said before, brakes have not always been a Harley-Davidson strong point — but we are prepared to give the XLH a pat on the head for its stopping power. It should be obvious that with a curb weight of 500 pounds the brakes have their work cut out for them, but they do the job. Drum diameter is still 8 inches, front and rear, but the front brake has acquired a die-cast aluminum drum, and the lining width has been increased to slightly more than 1.5-inches. A “reliable source” tells us that Harley-Davidson will use this new Sportster brake on the KR racing bikes, for road racing, so the company must have a lot of faith in the unit’s performance.

New, too, is the 12-volt electrical system, and according to the chaps at the local Harley-Davidson dealer’s shop (who have been almost painfully honest with us in the past and, on record, can be believed now), the 12-volt equipped machines have virtually no electrical problems. The customers’ habit of mounting constellations of extra lights does not appear to overtax the new electrical system, and there have been added benefits like extended ignition breaker-point life. Apparently, with the added voltage, an adequate spark is obtained with a lower current passing across the points, and the points last longer.

The Sportster is quite a comfortable motorcycle. The left footpeg vibrates noticeably (why the right does not we are not prepared to say) but it is otherwise reasonably smooth. Straight-line stability is good, but we felt obliged to treat corners with more than our customary amount of restraint. While the rubber-mounted handlebars do a dandy job of keeping vibration away from one’s hands, they give the steering a rather weird feel at times, and we were also bothered by a tendency for bits under the bike to begin scuffing the pavement at surprisingly moderate angles of lean. In all, the Sportster gives the impression that it is designed to be held more or less vertical, and steered by aiming the front wheel — like an automobile.

Control position was fine; no fumbling around required. However, we were again irritated by the excessive lash in the throttle linkage. The Sportster has a push-pull, no-return-spring throttle, and while this basic arrangement is good, we still think it is necessary to make the throttlebutterfly follow what the twist-grip is doing. With all the lash in the system, one must first move the grip enough to take up the slack before the engine responds. Some of the fineness of control is lost in the process.

What was probably the Sportster’s most endearing characteristic was something we remarked upon when we tested the XLCH: the “instant” power (just add throttle). The engine’s torque peak of 52 pounds-feet is at 3800 rpm, and you will get maximum results if the revs are somewhere between the torque and power peaks when throttle is wound-on, but with all of that displacement the engine simply won’t take “no” for an answer. Turn up the wick and you get action. This makes the Sportster a very handy instrument for carving through traffic — which is a good way to land in the hospital but the Sportster will certainly go along with the game if that’s the way you like to play.

We did like very much the aluminum alloy wheels on the bike given us for test, which are optional at a slight increase in cost. Optional, too, are the individual exhaust pipes and mufflers, and we are told that most of the bikes sold have these — the added cost is only in the order of $2 7.50. All motorcycles should be fitted with generator and oil pressure warning light (two-strokes and those bikes which have ammeters are exceptions). All motorcycles should also have handlebar grips like those on our Sportster: these had a fine-textured surface that gave a more comfortable, more secure grip than all of the ribbedwonders we have ever seen.

Styling is a matter of opinion, of course, but in our opinion the Sportster is rather a nice-looking motorcycle; looking much smaller and leaner than its actual physical dimensions would indicate. Moreover, it has one of the best-styled fuel tanks (fitted with a two-way main/reserve fuel valve) we have seen. Unfortunately, our test machine had flecks of dirt, or something, in its paint, and that tempered our enthusiasm for its looks.

Quite frankly, in the area of performance, we think that this particular machine was sub-standard. It would start easily enough (the automatic ignition retard was much appreciated) but it simply would not run very strong. This latest Sportster’s speed fell well short of that obtained with the XLCH, and it most definitely did not have a crisp feeling. Also, it was smoking rather badly, but this may well have been due to the change Harley-Davidson has made to chromed oil-control rings, which take longer to seat in properly. However, even sub-standard Sportsters are not slow, as our performance figures will show, and the man riding one will not be in any danger of getting shut-down by an upstart 250. •

HARLEY-DAVIDSON SPORTSTER XLH

SPECIFICATIONS

$1521.50

PERFORMANCE