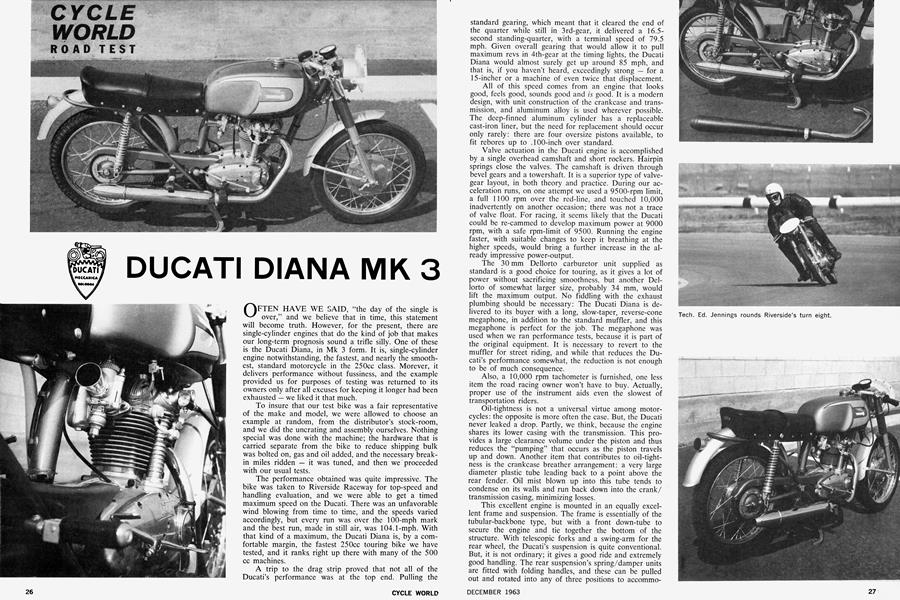

DUCATI DIANA MK 3

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

OFTEN HAVE WE SAID, “the day of the single is over,” and we believe that in time, this statement will become truth. However, for the present, there are single-cylinder engines that do the kind of job that makes our long-term prognosis sound a trifle silly. One of these is the Ducati Diana, in Mk 3 form. It is, single-cylinder engine notwithstanding, the fastest, and nearly the smoothest, standard motorcycle in the 250cc class. Morever, it delivers performance without fussiness, and the example provided us for purposes of testing was returned to its owners only after all excuses for keeping it longer had been exhausted — we liked it that much.

To insure that our test bike was a fair representative of the make and model, we were allowed to choose an example at random, from the distributor’s stock-room, and we did the uncrating and assembly ourselves. Nothing special was done with the machine; the hardware that is carried separate from the bike to reduce shipping bulk was bolted on, gas and oil added, and the necessary breakin miles ridden — it was tuned, and then we proceeded with our usual tests.

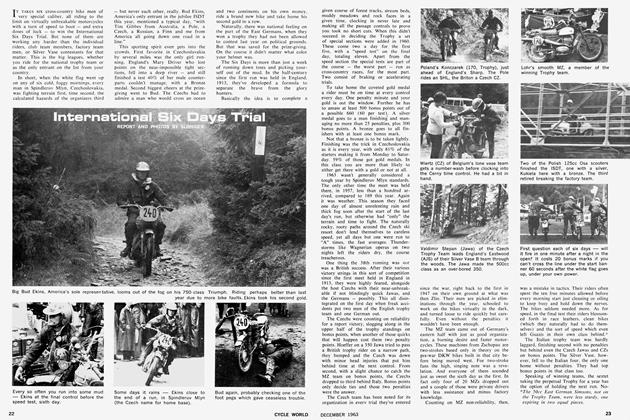

The performance obtained was quite impressive. The bike was taken to Riverside Raceway for top-speed and handling evaluation, and we were able to get a timed maximum speed on the Ducati. There was an unfavorable wind blowing from time to time, and the speeds varied accordingly, but every run was over the 100-mph mark and the best run, made in still air, was 104.1-mph. With that kind of a maximum, the Ducati Diana is, by a comfortable margin, the fastest 250cc touring bike we have tested, and it ranks right up there with many of the 500 cc machines.

A trip to the drag strip proved that not all of the Ducati’s performance was at the top end. Pulling the standard gearing, which meant that it cleared the end of the quarter while still in 3rd-gear, it delivered a 16.5second standing-quarter, with a terminal speed of 79.5 mph. Given overall gearing that would allow it to pull maximum revs in 4th-gear at the timing lights, the Ducati Diana would almost surely get up around 85 mph, and that is, if you haven’t heard, exceedingly strong — for a 15-incher or a machine of even twice that displacement.

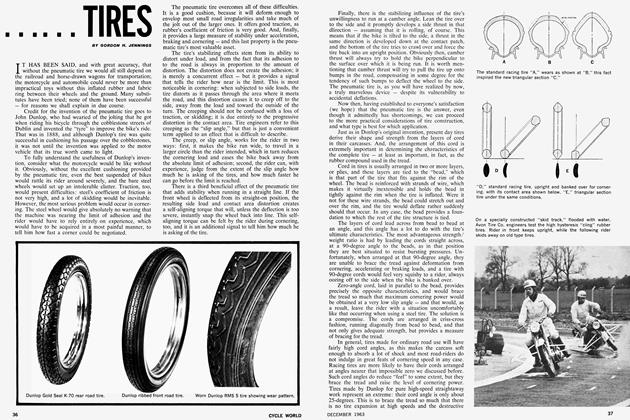

All of this speed comes from an engine that looks good, feels good, sounds good and is good. It is a modern design, with unit construction of the crankcase and transmission, and aluminum alloy is used wherever possible. The deep-finned aluminum cylinder has a replaceable cast-iron liner, but the need for replacement should occur only rarely: there are four oversize pistons available, to fit rebores up to .100-inch over standard.

Valve actuation in the Ducati engine is accomplished by a single overhead camshaft and short rockers. Hairpin springs close the valves. The camshaft is driven through bevel gears and a towershaft. It is a superior type of valvegear layout, in both theory and practice. During our acceleration runs, on one attempt we used a 9500-rpm limit, a full 1100 rpm over the red-line, and touched 10,000 inadvertently on another occasion; there was not a trace of valve float. For racing, it seems likely that the Ducati could be re-cammed to develop maximum power at 9000 rpm, with a safe rpm-limit of 9500. Running the engine faster, with suitable changes to keep it breathing at the higher speeds, would bring a further increase in the already impressive power-output.

The 30 mm Dellorto carburetor unit supplied as standard is a good choice for touring, as it gives a lot of power without sacrificing smoothness, but another Dellorto of somewhat larger size, probably 34 mm, would lift the maximum output. No fiddling with the exhaust plumbing should be necessary: The Ducati Diana is delivered to its buyer with a long, slow-taper, reverse-cone megaphone, in addition to the standard muffler, and this megaphone is perfect for the job. The megaphone was used when we ran performance tests, because it is part of the original equipment. It is necessary to revert to the muffler for street riding, and while that reduces the Ducati’s performance somewhat, the reduction is not enough to be of much consequence.

Also, a 10,000 rpm tachometer is furnished, one less item the road racing owner won’t have to buy. Actually, proper use of the instrument aids even the slowest of transportation riders.

Oil-tightness is not a universal virtue among motorcycles: the opposite is more often the case. But, the Ducati never leaked a drop. Partly, we think, because the engine shares its lower casing with the transmission. This provides a large clearance volume under the piston and thus reduces the “pumping” that occurs as the piston travels up and down. Another item that contributes to oil-tightness is the crankcase breather arrangement: a very large diameter plastic tube leading back to a point above the rear fender. Oil mist blown up into this tube tends to condense on its walls and run back down into the crank/ transmission casing, minimizing losses.

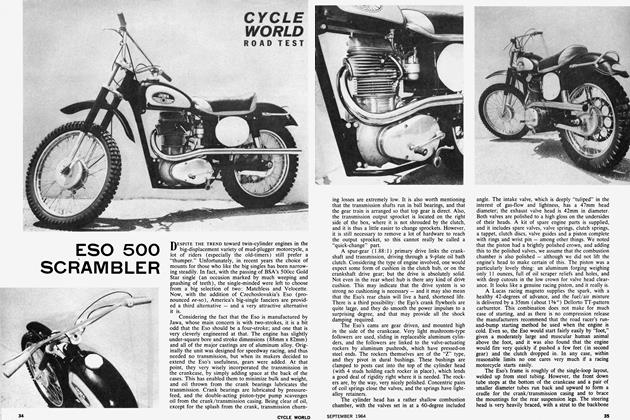

This excellent engine is mounted in an equally excellent frame and suspension. The frame is essentially of the tubular-backbone type, but with a front down-tube to secure the engine and tie together the bottom of the structure. With telescopic forks and a swing-arm for the rear wheel, the Ducati’s suspension is quite conventional. But, it is not ordinary; it gives a good ride and extremely good handling. The rear suspension’s spring/damper units are fitted with folding handles, and these can be pulled out and rotated into any of three positions to accommodate varying loads.

The brakes, too, deserve high praise. They are large, and of finned aluminum (with an iron liner) and have more than enough capacity. The front backing plate has a scoop-type inlet and outlet for cooling air. The rear hub carries not only the brake assembly, but a “cush” assembly to absorb shock in the drive.

Handling tests were done at Riverside Raceway, which has just about every kind of corner, and it was while doing this bit of test riding that we really began to like the Ducati. The bike’s “clip-on” handlebars are too low for touring-type riding, but they are perfect for road-racing. Future models will be delivered with two sets of bars, one a new higher and wider clip-on bar that should be nearly ideal for touring. There is enough wind pressure, when running at high speeds, to take the weight from one’s wrists, and the overall positioning of the bars and seat was very good. The seat itself was, unfortunately, too narrow — which seems to be more or less typical of Italian bikes.

Cornering speeds on the Ducati were limited only by the height of the foot-pegs and megaphone — which would “ground” and force the rider to ease-off before the suspension and tires were at the limit. Of course, those pegs are fairly high, and by overall touring standards, the Ducati is cornering very fast indeed when it runs out of “lean.” And, under all circumstances, it is steady and controllable, with no bad habits. We all had a whack at “road-racing,” and were delighted with its behavior. Not with the handling alone, but with the brakes, and particularly, with the smoothness and willingness of the engine. All theoretical considerations aside, there is a lot to be said for a good, strong single. The transmission ratios are a bit too widely spaced for road racing, but they are just the thing for touring. The gear change is of the rocker type, and we liked that. Changes, up or down, can be made with a good, solid punch of the foot, and it reduces the chances of missing a shift. The Ducati was quite smooth-shifting, generally, but it was necessary to give the lever a vigorous jab, at times, to get into 4th gear.

The only trace of temperament displayed was an occasional reluctance to start when hot. We think that this failing was almost entirely due to the kick-starter layout, which has the pedal over on the wrong side, for most of us, and had a lever that was simply too short. With the Ducati’s 10:1 compression, it takes a lot of pressure to get a rapid run-through, and the short-throw kick lever didn’t help things a bit. We did find, though, that it would run-and-bump start very easily every time.

One added reason for the touchy starting was the ignition system, which uses a flywheel magneto in place of the usual Ducati battery and coil. With this setup, unless the engine is run through smartly, there is no spark. Current for the lighting system also came from the flywheel dynamo.

In its appearance, the Ducati Diana is second to none. The overall finish is superb, especially in the care applied in polishing the many aluminum castings. The low bars lend a lot of raciness to its appearance, and so does the big 5-gallon fuel tank, which has knee-notches and a quick-release filler cap that not only look racy but are functional as well. In all, we were absolutely enchanted with the Ducati Diana; we think you will be too.

DUCATI

DIANA MK 3

SPECIFICATIONS

$689

PERFORMANCE

POWER TRANSMISSION

DIMENSION,IN

ACCELERATION