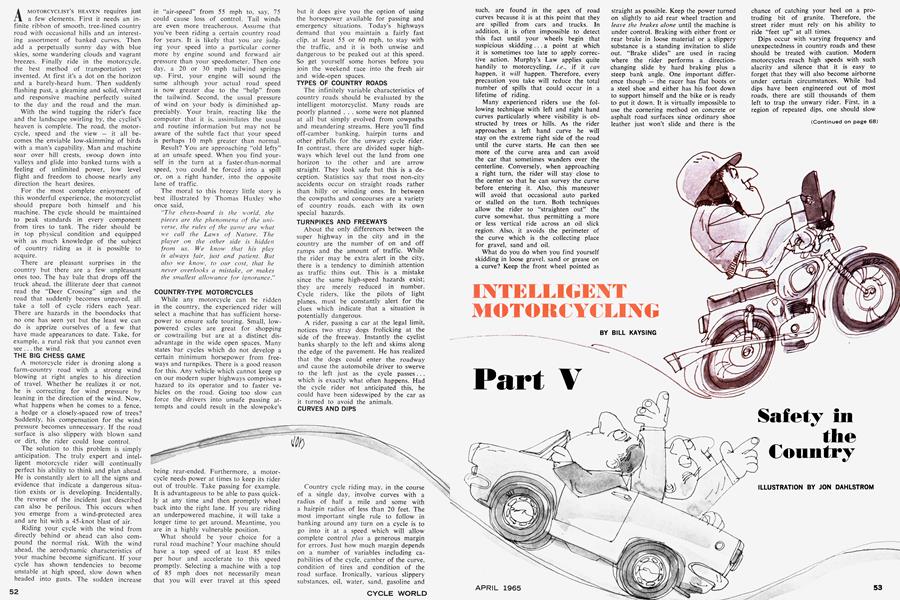

A MOTORCYCLIST’S HEAVEN requires just a few elements. First it needs an infinite ribbon of smooth, tree-lined country road with occasional hills and an interesting assortment of banked curves. Then add a perpetually sunny day with blue skies, some wandering clouds and vagrant breezes. Finally ride in the motorcycle, the best method of transportation yet invented. At first it’s a dot on the horizon and a barely-heard hum. Then suddenly flashing past, a gleaming and solid, vibrant and responsive machine perfectly suited to the day and the road and the man.

With the wind tugging the rider’s face and the landscape swirling by, the cyclist’s heaven is complete. The road, the motorcycle, speed and the view — it all becomes the enviable low-skimming of birds with a man’s capability. Man and machine soar over hill crests, swoop down into valleys and glide into banked turns with a feeling of unlimited power, low level flight and freedom to choose nearly any direction the heart desires.

For the most complete enjoyment of this wonderful experience, the motorcyclist should prepare both himself and his machine. The cycle should be maintained to peak standards in every component from tires to tank. The rider should be in top physical condition and equipped with as much knowledge of the subject of country riding as it is possible to acquire.

There are pleasant surprises in the country but there are a few unpleasant ones too. The hay bale that drops off the truck ahead, the illiterate deer that cannot read the “Deer Crossing” sign and the road that suddenly becomes unpaved, all take a toll of cycle riders each year. There are hazards in the boondocks that no one has seen yet but the least we can do is apprize ourselves of a few that have made appearances to date. Take, for example, a rural risk that you cannot even see .. . the wind.

THE BIG CHESS GAME

A motorcycle rider is droning along a farm-country road with a strong wind blowing at right angles to his direction of travel. Whether he realizes it or not. he is correcting for wind pressure by leaning in the direction of the wind. Now, what happens when he comes to a fence, a hedge or a closely-spaced row of trees? Suddenly, his compensation for the wind pressure becomes unnecessary. If the road surface is also slippery with blown sand or dirt, the rider could lose control.

The solution to this problem is simply anticipation. The truly expert and intelligent motorcycle rider will continually perfect his ability to think and plan ahead. He is constantly alert to all the signs and evidence that indicate a dangerous situation exists or is developing. Incidentally, the reverse of the incident just described can also be perilous. This occurs when you emerge from a wind-protected area and are hit with a 45-knot blast of air.

Riding your cycle with the wind from directly behind or ahead can also compound the normal risk. With the wind ahead, the aerodynamic characteristics of your machine become significant. If your cycle has shown tendencies to become unstable at high speed, slow down when headed into gusts. The sudden increase in “air-speed” from 55 mph to, say, 75 could cause loss of control. Tail winds are even more treacherous. Assume that you’ve been riding a certain country road for years. It is likely that you are judging your speed into a particular corner more by engine sound and forward air pressure than your speedometer. Then one day, a 20 or 30 mph tailwind springs up. First, your engine will sound the same although your actual road speed is now greater due to the “help” from the tailwind. Second, the usual pressure of wind on your body is diminished appreciably. Your brain, reacting like the computer that it is, assimilates the usual and routine information but may not be aware of the subtle fact that your speed is perhaps 10 mph greater than normal.

Result? You are approaching “old lefty” at an unsafe speed. When you find yourself in the turn at a faster-than-normal speed, you could be forced into a spill or, on a right hander, into the opposite lane of traffic.

The moral to this breezy little story is best illustrated by Thomas Huxley who once said.

“The chess-board is the world, the pieces are the phenomena of the universe, the rides of the game are what we call the Laws of Nature. The player on the other side is hidden from us. We know that his play is always fair, just and patient. But also we know, to our cost, that he never overlooks a mistake, or makes the smallest allowance for ignorance.”

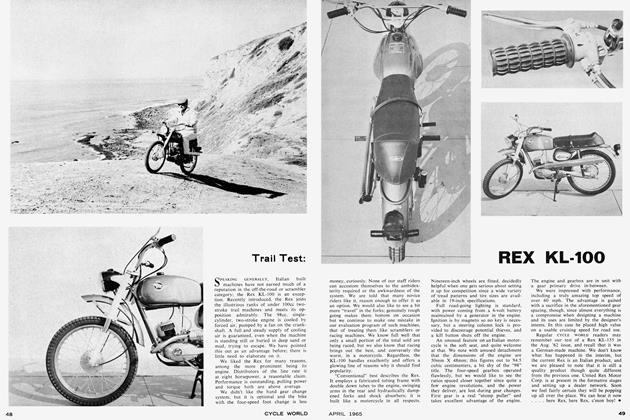

COUNTRY-TYPE MOTORCYCLES

While any motorcycle can be ridden in the country, the experienced rider will select a machine that has sufficient horsepower to ensure safe touring. Small, lowpowered cycles are great for shopping or cowtrailing but are at a distinct disadvantage in the wide open spaces. Many states bar cycles which do not develop a certain minimum horsepower from freeways and turnpikes. There is a good reason for this. Any vehicle which cannot keep up on our modern super highways comprises a hazard to its operator and to faster vehicles on the road. Going too slow can force the drivers into unsafe passing attempts and could result in the slowpoke’s

being rear-ended. Furthermore, a motorcycle needs power at times to keep its rider out of trouble. Take passing for example. It is advantageous to be able to pass quickly at any time and then promptly wheel back into the right lane. If you are riding an underpowered machine, it will take a longer time to get around. Meantime, you are in a highly vulnerable position.

What should be your choice for a rural road machine? Your machine should have a top speed of at least 85 miles per hour and accelerate to this speed promptly. Selecting a machine with a top of 85 mph does not necessarily mean that you will ever travel at this speed but it does give you the option of using the horsepower available for passing and emergency situations. Today’s highways demand that you maintain a fairly fast clip, at least 55 or 60 mph, to stay with the traffic, and it is both unwise and dangerous to be peaked out at this speed. So get yourself some horses before you join the weekend race into the fresh air and wide-open spaces.

TYPES OF COUNTRY ROADS

The infinitely variable characteristics of country roads should be evaluated by the intelligent motorcyclist. Many roads are poorly planned . . . some were not planned at all but simply evolved from cowpaths and meandering streams. Here you’ll find off-camber banking, hairpin turns and other pitfalls for the unwary cycle rider. In contrast, there are divided super highways which level out the land from one horizon to the other and are arrow straight. They look safe but this is a deception. Statistics say that most non-city accidents occur on straight roads rather than hilly or winding ones. In between the cowpaths and concourses are a variety of country roads, each with its own special hazards.

TURNPIKES AND FREEWAYS

About the only differences between the super highway in the city and in the country are the number of on and off ramps and the amount of traffic. While the rider may be extra alert in the city, there is a tendency to diminish attention as traffic thins out. This is a mistake since the same high-speed hazards exist; they are merely reduced in number. Cycle riders, like the pilots of light planes, must be constantly alert for the clues which indicate that a situation is potentially dangerous.

A rider, passing a car at the legal limit, notices two stray dogs frolicking at the side of the freeway. Instantly the cyclist banks sharply to the left and skims along the edge of the pavement. He has realized that the dogs could enter the roadway and cause the automobile driver to swerve to the left just as the cycle passes.. . which is exactly what often happens. Had the cycle rider not anticipated this, he could have been sideswiped by the car as it turned to avoid the animals.

CURVES AND DIPS

Country cycle riding may, in the course of a single day, involve curves with a radius of half a mile and some with a hairpin radius of less than 20 feet. The most important single rule to follow in banking around any turn on a cycle is to go into it at a speed which will allow complete control plus a generous margin for errors. Just how much margin depends on a number of variables including capabilities of the cycle, camber of the curve, condition of tires and condition of the road surface. Ironically, various slippery substances, oil, water, sand, gasoline and such, are found in the apex of road curves because it is at this point that they are spilled from cars and trucks. In addition, it is often impossible to detect this fact until your wheels begin that suspicious skidding... a point at which it is sometimes too late to apply corrective action. Murphy’s Law applies quite handily to motorcycling, i.e., if it can happen, it will happen. Therefore, every precaution you take will reduce the total number of spills that could occur in a lifetime of riding.

INTELLIGENT MOTORCYCLING Part V

BILL KAYSING

Safety in the Country

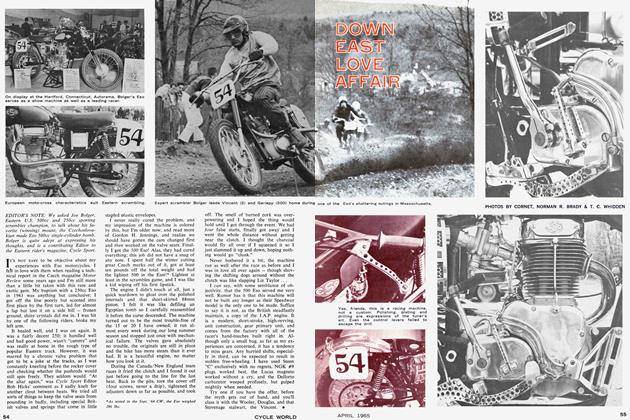

Many experienced riders use the following technique with left and right hand curves particularly where visibility is obstructed by trees or hills. As the rider approaches a left hand curve he will stay on the extreme right side of the road until the curve starts. He can then see more of the curve area and can avoid the car that sometimes wanders over the centerline. Conversely, when approaching a right turn, the rider will stay close to the center so that he can survey the curve before entering it. Also, this maneuver will avoid that occasional auto parked or stalled on the turn. Both techniques allow the rider to “straighten out” the curve somewhat, thus permitting a more or less vertical ride across an oil slick region. Also, it avoids the perimeter of the curve which is the collecting place for gravel, sand and oil.

What do you do when you find yourself skidding in loose gravel, sand or grease on a curve? Keep the front wheel pointed as straight as possible. Keep the power turned on slightly to aid rear wheel traction and leave the brakes alone until the machine is under control. Braking with either front or rear brake in loose material or a slippery substance is a standing invitation to slide out. “Brake slides” are used in racing where the rider performs a directionchanging slide by hard braking plus a steep bank angle. One important difference though — the racer has flat boots or a steel shoe and either has his foot down to support himself and the bike or is ready to put it down. It is virtually impossible to use the cornering method on concrete or asphalt road surfaces since ordinary shoe leather just won’t slide and there is the chance of catching your heel on a protruding bit of granite. Therefore, the street rider must rely on his ability to ride “feet up” at all times.

Dips occur with varying frequency and unexpectedness in country roads and these should be treated with caution. Modern motorcycles reach high speeds with such alacrity and silence that it is easy to forget that they will also become airborne under certain circumstances. While bad dips have been engineered out of most roads, there are still thousands of them left to trap the unwary rider. First, in a region of repeated dips, one should slow down on general principles. After all. a dip may contain something ... a stalled car. a carton, rocks or two feet of water . . . that you cannot see until you are at the edge looking down. By then, at any speed of consequence, it may be too late to avoid collision.

(Continued on page 68)

Second, at high speed, it is possible to be launched a few inches or more when leaving the opposite side of a dip. This free floating sensation is wonderful but the first reaction of a novice rider is to brake and this is not good. If the brake is applied while a cycle is in the air, as soon as it touches the road surface again, the tire grabs a handful of road and a violent braking action results. This event, coupled with a slightly cocked front wheel could cause a crash. If you find yourself off the ground going over a rise, leave the brakes alone. Keep the throttle at about the same position, slide back on the seat, pull up slightly on the bars to keep the front wheel up and your rear wheel will touch down again as lightly as a proverbial feather. Practicing this technique over a slight rise will teach you that “jumping” a cycle is quite simple and a lot of fun to boot.

MOUNTAIN MEANDERS

Riding your motorcycle in areas where the roads are edged by steep slopes and cliffs requires extra attention. What are some of the hazards unique to mountain driving? Well, how about the time you swept around an escarpment and found several large chunks of rock that had just fallen from the steep ledge above? Then there was the hole, two feet deep and three feet across, caused by water erosion under the pavement. Besides these perils there are road construction barricades, shady icy spots, slow-moving graders, mountain goats and sports car drivers making like Moss and using both sides of the road. Probably the best overall rule for cliff country is to reduce speed until you leave it in one piece.

STREAMS AND RIVERS

On occasion, a rural road will ford a small stream or river. Unless the water is shallow and clear enough to see the character of the bottom, slow down to a walk before you cross. If there is any question as to depth, find another ford. Even though you may not mind getting wet, your engine block won’t forgive a chilly dousing. Attempts to ride quickly through even shallow streams may result in loss of control since there is no way of knowing what odd-shaped boulders or off-angle channels are concealed beneath the surface.

WOODS AND FORESTS

Places doing the tree bit usually contain an abundance of wildlife ... deer, elk, moose, plus many smaller varieties like ’possum, ’coon and skunk. Collision with any species at speed could be harder on your family than theirs. Consequently, maintain a sharp lookout, be ready to stop, and stay lucky.

There is an obscure hazard native to forested regions. While riding between thick stands of trees your eyes will become accustomed to the relatively dim light. Then, as you emerge from the gloom and enter brightly lit patches of clearing, you are momentarily blinded. At times, these areas of alternating dark and bright occur swiftly and the eye has little chance to adjust itself. Since many adverse things can occur in milliseconds, rotate the throttle clockwise until you can see.

DESERTS, PLAINS AND PRAIRIES

While most regions in the eastern United States have wooded hills, picturesque lakes and other natural beauty, the middle and far west can become monotonous. Almost all riders have had the experience of beginning a cycle trip across the flatlands determined to maintain a consistent and prudent speed. Then, after hours of steady riding, they find the speedometer needle has climbed unnoticed until they are traveling at a clip all out of proportion to road conditions and original intentions.

So stop once in a while! Preferably at regular intervals .. . say every 50 minutes, for a 5 or 10 minute break. In this way the rider becomes adjusted to a safe, steady and consistent pace across the vast reaches rather than an ever-faster trip to the “undiscovered country.” In agricultural regions there is one special hazard: farm machinery. The wheeled

goodies that our farmer friends use just won’t cut it on the drag strip. Watch out for them creeping out of fields and don’t overestimate their speed as you overtake them. Most are moving so slowly as to comprise a stationary obstacle. Being full of all kinds of rods, wheels and steel teeth, they are most indigestible to the average cycle rider.

SPECIAL HAZARDS

The white-painted hives of bees are a familiar sight alongside many rural roads. Give the hives a wide berth because there are normally a large number of bees leaving or returning to their hive and the chances of accidentally intercepting one or two are quite good. If one lands on you to make with the stinger, don’t panic or attempt to brush him off. It’s too easy to ride off the road or swerve into the other lane... just pull to a halt and attend to it while safely stationary.

Inclement weather can add a few problems to the country tourist’s existing supply. Rain is probably the greatest single weather factor in cycle accidents. It works against the rider in many ways:

1. It lessens visibility.

2. It hinders the use of goggles, shields and other vision protecting devices.

3. It increases the possibility of spills.

4. It causes discomfort and lessens attentiveness.

There are probably only two suitable methods of coping with rainy days as far as cycles are concerned. The first is to stay home or take your car. The second is to ride with the mental attitude that you are traveling on a sheet of oil-coated glass enhanced here and there by large patches of greased BB’s. This attitude should help give you the sensitivity of response and precise control necessary to stay up on rain-slick pavement.

Rain-swept rural macadam is a picnic compared to the hackle-raising thrills of icy pavement. Although it is done constantly, riding on icy country roads is more foolish than fun. You can ride like Jim Redman and still not notice that patch of ice in the shade on Turn 9 west of Truckee. Even going slow doesn’t always ensure a safe passage over the ice since an uncontrollable skid can start at any time.

“Slow down at Sundown” is an admonition for our four-wheeled friends that holds twice as true for us. Cycle riding at night on country roads, especially unfamiliar ones, is a test of all the skill, intelligence and experience that a rider can muster. For a motorcyclist to ride “beyond his lights” is senseless; he should always ride well within the beam of his headlight so that any obstructions can be seen and avoided. A 4,000 pound car can easily run over a large object in the road without difficulty. Obviously, a motorcycle weighing less than 500 pounds and storing much less in the “foot-pounds-ofenergy” department is usually going to come out second best in a collision with such an object. Nocturnal strollers, both two and four-legged are another nighttime problem, particularly since many cycle riders stay quite close to the right hand side of the road.

SPEED IN THE COUNTRY

Speed all by itself causes no problem. We all travel at about 19 miles per second around the sun and it doesn’t ruffle anyone’s feathers. Astronauts make with five figure speeds around the earth and enjoy the flight pay. A motorcycle traveling at high speed has great stability (stability being a linear function of speed). Anyone who has tried to ride in deep sand knows that a greater velocity gives greater control. However, there is one serious drawback to high speed ... the time in which a rider must take positive action against a hazard becomes unbelievably short, as the figures in the following chart indicate. (While stopping distances are based on automobiles, any well-made cycle should be able to stop as fast or faster than any equivalent car.)

These figures include both reaction time and braking distance and are based on the ideal situation: good brakes, good

tires and dry concrete. As may be seen, stopping distance at sixty miles per hour is about six times as great as at twenty although the speed is only three times as much. While this may sound like dry statistics, take a good look at the next chart compiled from National Safety Council figures.

It is clear from this chart that approximately doubling his speed increases an individual’s risk about 3V4 times. The conclusion to be drawn here is clear: keep your speed within reasonable limits and extend your riding career indefinitely. This is not stated to encourage “old lady” type riding wherein you risk tickets for going too slow on a turnpike or freeway. Quite the contrary, it is stated to encourage the less experienced riders to stay well within their skill and experience limits and to remind the old timers to allow a litle more margin for errors and the unexpected.

So tour the beautiful countryside on your motorcycle and have fun but always ride within your own limitations, those of your cycle and the limitations imposed by the road, traffic, visibility and weather conditions. •

*Fatalities per 1000 injury-type accidents