MIGHTY MARATHONS OF THE MOTOR-BIKES

J. L. BEARDSLEY

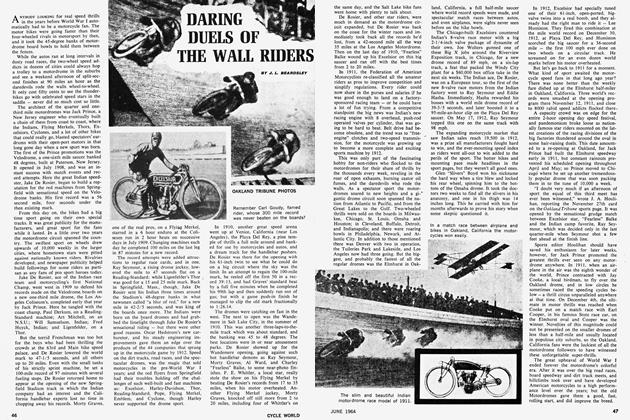

The one-third mile motordrome saucer tracks at Paterson, New Jersey and Springfield, Massachusetts were the launching pads that sent motorcycle racing soaring to immense popularity across the country; and by 1913 the lusty young sport already had the men and machines to invade the nation's dirt tracks, and the big auto road race courses at Elgin, Illinois; Savannah's Vanderbilt Cup track; and establish others of their own. On these noted circuits they challenged their four-wheeled rivals for top honors in land speed and sometimes topped them in spine-tingling thrills.

Venice. California; Sioux City. Iowa; Wichita. Kansas: Marion. Indiana: anti

Denver. Colorado, were other arenas of thunder-bike classics, but greatest of all was the annual July 4th. 300-mile National Championship at Dodge C ity. Kansas, the real "Indianapolis of the Motorbikes." where it took speeds that look good by today's standards to win the old "Coyote Classic" in the historic Cowboy Capital.

The old professional factory teams, riding on a salary and all-winnings basis, were a rugged bunch who took a lot of chances as a matter of course; but in the boom years of the big-time pro sport before and after the first World War some of the old-time cycle jockeys grossed $20,000 a year — and that wasn’t hay at 1920 prices and no large income taxes.

The tempo of the sport increased with improved mechanical design. The Indian company brought out Oscar Hedstrom’s overhead 8-valvc racing motor in 1912. and by 1913 the Milwaukee-built HarlcvDavidson followed suit with their own version of these fast motors using two intake and two exhaust valves per cylinder.

Racing motors were all special 61-inch twins, but the Excelsiors countered the 8 valves with 214-inch valves on their hot jobs that came out of the Chicago plant of this progressive concern.

Other good machines that gave the big three trouble on the tracks were Flying Merkle. of Middletown. Ohio, with spring frame and a ball-bearing motor: the Thor from Aurora. Illinois; Reading-Standard. "Built anti Tested in the Mountains.” out in Reading, Pennsylvania; all were once big names in motorcycling and the record books.

But mention of the Cyclone of 1914-15 always brings a gleam to the eye of oldtime racing men. This potentially great machine was built in St. Paul. Minnesota by the Jocrns Motor Manufacturing Company. boasted a ball-bearing motor with overhead cam operated by bevel gear driven shafts. The valve rockers had rocking stirrups on the ends to eliminate sidethrust. The magneto was shaft-drive, and it had pump lubrication and three-speed transmission, but that camshaft was an early example of a design widely used on high performance motors for years. It certainly w-as capable of further development; but even without this, the old Cyclone was a sensational race track performer in its day.

And sensational was the word. too. for the way the old thunderbike jockeys rode rough courses at terrific speed. The vibration from those 234-inch tires inflated to I 10 pounds was but one hardship the oldtime riders faced on the roaring road circuits. The heavy felt pads placed on top of the gas tank to protect the rider’s chest would have a hole pounded all the way through before a long race ended in the old days, and when that happened they never turned any handsprings even though they won.

Still, the old boys gloried in their hard knocks, and 1916 Champion Irv Janke was proud to recite his long list of broken bones.

"We never dragged our feet in those days as they do now.” he was always quick to say. "That would have slowed us up. and would stir up a lot of dust for the riders following, so it w-as against tfie rules.”

Class A was professional racing at its best. The manufacturers footed all the bills, and supplied the machines and parts, and mechanics — all the rider had to do was to get the checker first, and stay between the fences — if he could.

The big three usually set up headquarters at important race meets in huge tents, and the names Indian. Harley-Davidson. or Excelsior were spread in huge letters across the front in true circus style, for these were in fact carnivals of speed. The tents served as workshops and a rider's rendezvous — this is a ten-dollar word meaning crap game.

As the first American motorcycle and first out with their 8-valve race motors, the Indian camp had it made in 1913 and '14 on the dirt as well as the boards. It was evident as the bike riders invaded the famous auto road race circuit at F.lgin. Illinois, where De Palma. Mulford, Cooper. Oldfield, Pullen, and all the top speed kings thrilled thousands in the F.lgin National I rophy and other cup classics. On July 4th. 1913, the hot handlebar twisters took over in a 254-mile marathon of speed and spills promoted by the Chicago Motorcycle Club.

The July 4th holiday was also picked by The Denver Tost and the Federation of American Motorcyclists for another big distance event, a 200-mile road race in the Colorado metropolis. Here co-winners Glen Boyd and Bert Bruggerman combined talents to set a new' pro record on their Indian of 3:25:54.25, and second went to Larry Fleckenstein and Curley Fredericks, so the dual-rider system paid off for Indian by clipping 40 minutes off the previous record for this distance.

Excelsior hit the headlines on August 24, 1913, w'hen their ace distance rider. Carl Goudy, roared around the Columbus, Ohio, mile track 100 times in 92 minutes for a world circular flat track record.

But the biggest motorcycle race of the old days was already in the works. While enroutc to the Federation of American Motorcyclists convention in Denver, in 1913, a club called “the Short Grassers” from Hutchinson. Kansas discovered a new 2-mile dirt track at Dodge City, and carried a glowing description of it to the convention. The idea was enthusiastically received by the convention and the whole motorcycle trade began to set up the biggest motorcycle classic in all history on the Dodge City oval. Only the 4th of July would be adequate for a 300-Mile International Championship, and seven motorcycle manufacturers groomed their best machines and rounded up the top riding stars to bid for the immense prestige of a victory in the 1914 inaugural.

Harley-Davidson’s new racing team would get its first test in big-time competition over a distance route here, and they sent AÍ Stratton, Walt Cunningham, Paul Garst, and Paul Gott into the Dodge City derby.

The first of the “Coyote Classics” w'as flagged away by Dr. B. J. Patterson. F.A.M. president, after a one-lap circuit of the two-mile oval, and as he waved the green flag 36 daredevils roared away, six abreast. Lee Taylor on a Flying Merkle went drilling into the first turn ahead of the pack; he was still there at the end of the lap and stayed up front for 60 miles until Walt Cunningham. H-D. closed a 12 second lead to get past him. He set a hot pace, but at 120 miles Glen Boyd gunned his Indian 8-valve into first place. Cunningham tried desperately to get even with the rocketing Indian speedster but never quite made it. and a broken chain put him into the pits at 180 miles.

Reeling off the laps with clock-like precision. Boyd was never in danger and won over Bill Brier. Thor, and Carl Goudy, Excelsior.

There were constant and growing dirt track meets to fill in between the big races, and the next distance event was staged on the famous Vanderbilt Cup course at Savannah. Georgia, where the great drivers and cars of America and Europe matched horsepower for the w'orld's highest speed honors. This Dixie haven of speed was host to the thunderbikes on Thanksgiving Day. 1914, in a 300-mile contest under the palm and magnolia trees that lined this excellent 17-mile course. The Turkey Day fans saw' a wild exhibition of terrific speed as Lee Taylor, on an Indian, outsped a good field to win in 5:02.32. but was chased right to the wire by 19-year-old Irving Janke. the “Boy Wonder” from Harley-Davidson’s hometown, riding one of the Milwaukee-made machines.

Following the automobile pattern, motorcycle road racing w'as a big time sport in 1915. a sure-fire public demonstration of a motorcycle’s qualities against all rivals under actual road conditions. The big three were now bidding against each other for contracts with the top race riders, for motorcycles in those days were only as good as their race track rating. Racing w'as governed, originally, by competition regulations for three classes of riders:

Professional — A rider on salary for any company, riding their machines in races anywhere in the country, with privilege of all purses won.

Trade Rider — Any competitor with a trade affiliation, and competing with trade assistance, but retaining amateur standing.

Amateur — Private owner racing for sport, and non-cash awards: cups,

trophies, medals, etc.

Some abuses in the Trade Rider class developed when contestants left their local districts to compete tot purses elsewhere. and amendments were added restricting Trade Riders to a 100 mile — and later 200 mile — radius of his home.

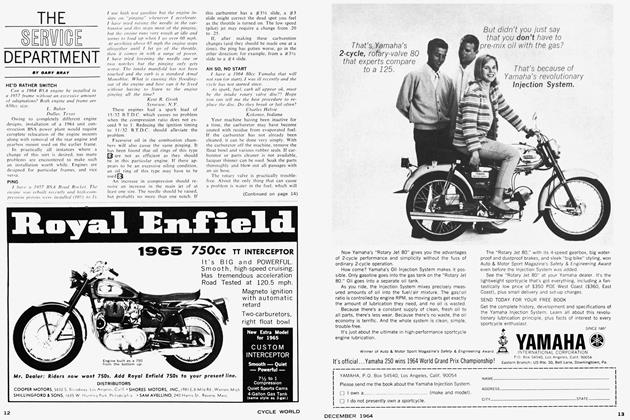

By 1915 the partnership that William S. Harley and Arthur Davidson formed in 1903. using a shed back of Davidson's home as a shop, had grown to one of Milwaukee's great industries, building over 17.000 motorcycles each year.

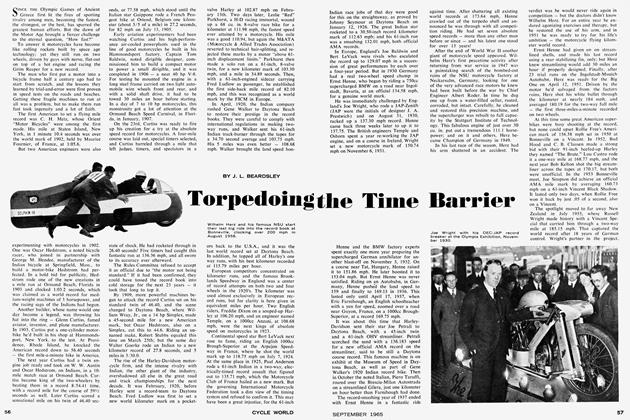

Racing had helped Harley-Davidson to success - and it would help them much more. They had built a formidable racing team for the 1915 campaign, adding one of the sport’s immortals. Otto Walker: and from the drome circuit they acquired Leslie "Red" Parkhurst, another great with a world of color; Joe Wolters, from the Excelsior camp wore their colors; Bill Brier from Thor. Roy Artley. and Harry Crandall were other aces in their hand. too.

The line-up for the 300-mile road race at Venice. California in April 1915. was a Who’s-Who of the pro ranks. For H-D there were Walker. Wolters. Parkhurst and Artley. Indian countered with Ray Creviston. Morty Graves, AI Ward. Fred Ludlow, F. H. Baker, and K. H. Verri 11. Excelsior named Carl Goudy. Glen Stokes. Bob Perry (their engineer-rider), and Montgomery. I here was Harry Brant for Thor; Fred Nemic, on a Dayton; and Heffelfinger and Tobcy on Popes.

But after the dust had settled. Otto Walker sat in the winner’s circle with a new' world record average of 68.31 mph; Parkhurst. H-D. was 2nd; C arl Goudy. Excelsior. 3rd; Bob Perry, Excelsior. 4th; Fred Ludlow, Indian, 5th; and Morty Graves. Indian. 6th; the purse was $2000.

At Ft. Dodge. Kansas, Otto Walker racked up another first for Harley in a 234-mile road event, while Red Parkhurst did the same in a 150-mile grind at Oklahoma City for his new bosses. This hectic affair was run over a course so rough one of the gas tank supports on Parkhurst’s Harley broke and he held the tank in place with one arm for the closing few miles to win the hard way.

Over 16.000 fans were on hand anticipating the year's greatest speed battle at Dodge City when the second 300-mile "Coyote Classic" was run on July 4th. 1915. Competition Chairman of the F.A.M. veered his pace car out of the way just in time as 29 men on 61-inch metal mustangs went power-sliding into the first turn in a made-made tornado of dust. Don Johns outscrambled the pack on the first lap and set a terrific pace to hold the lead over Lee Taylor, and Glen Stokes, who was moving fast on his Excelsior. At 100 miles it looked good for the Excelsiors when Carl Goudy took command with a record time of 1:14.10.

At 140 miles. Otto Walker pushed his Harley into the lead, but Morty Graves. Excelsior, hung doggedly to second, though Joe Wolters, and Harry Crandall, on Harleys, were breathing down his neck. At 200 miles Walker had set a world’s record time of 2:32.58. but none of the seven other Harley riders could budge Graves from second. He might spoil the day for the Harley team if something happened to Walker — and it did. A flat put Graves ahead, followed by Harry Crandall. H-D. but Carl Goudy. Excelsior’s ace. wats coming fast in third.

Walker regained the lead and as Graves was battling him gamely after running second for over 200 miles, his gas tank suddenly sprung a leak and his race was over. Walker went on to wan in 3:55.45 at a world record average of 76.27 mph. Six of the first seven finishers were Harleys: Carl Goudy, third on an Excelsior, was the only exception.

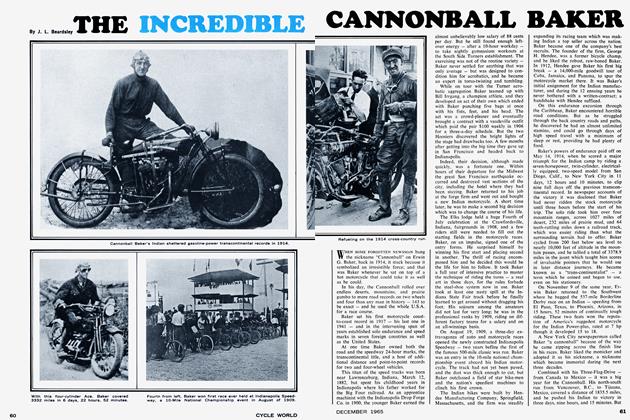

Two newcomers stole the entire show at the 1916 Dodge City 300-mile bike derby — Floyd Clymer, and Irving Janke, a born rider on the way up. These tw'o, mounted on Harleys, staged a hectic, wheel-to-wheel duel for 150 miles that had the nearly 20.000 fans shouting themselves hoarse. Never more than a few yards apart, they dueled on with neither giving a foot of ground if he could help it.

Every road race record from I to 300 miles was nailed down by this pair of handlebar wizards. Clymer. riding Otto Walker's 1915 winning machine/ set a one-hour mark of 83.62 miles, and a 100-mile time of 1:11.45, both world records.

Janke, in the lead at 200 miles made it in 2:27.18, for another: and when Clymer’s motor failed at 220 miles, Janke never slackened his torrid pace and ended with a 300-mile mark of 3:45.36 to slash almost eleven minutes off the old record. Joe Wolters, Excelsior, was second and about nine minutes ahead of the former mark, so Janke had no time to coast.

Ray Creviston. on an Indian, was the year’s 5and 10-mile dirt track champ, w'hile Ray Weishaar, H-D, won the 100mile track National at Detroit.

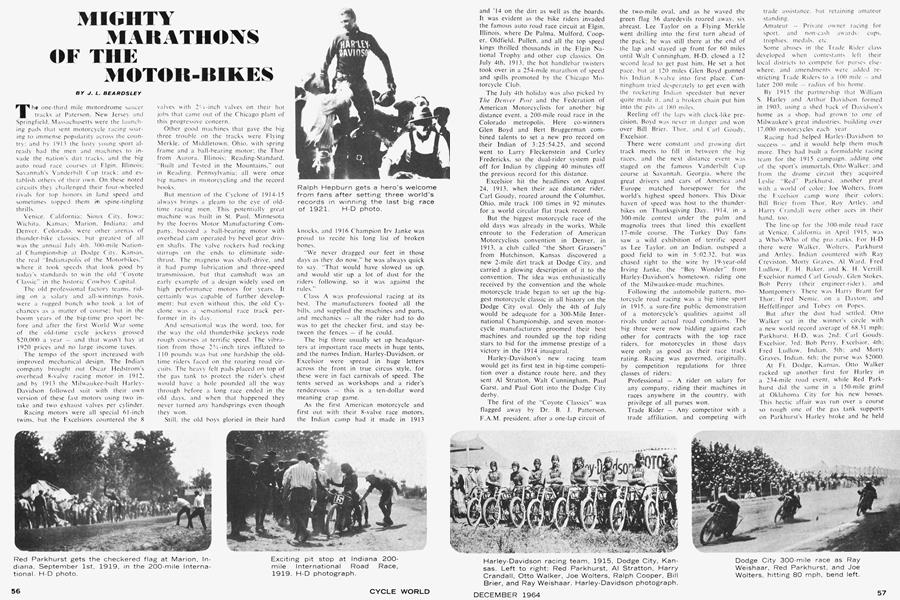

The first big road event following the end of the first World War w'as the 200-mile International Road Race at Marion, Indiana, Sept. 1, 1919. The

course was 5 miles with two long straights connected by sharp curves, and an estimated 15,000 fans were on hand to see this post-war revival of motorcycle speed and sport. Red Parkhurst scored a win for the Harley camp at 66.6 mph, and in second place was another young rider on his first factory race job sponsored by Harley-Davidson — Rxilph Hepburn, one of the all-time greats on two wheels and four. Ray Weishaar, H-D, won there in 1920.

Shorter races w'ere becoming popular in 1920. and Ten Buckner, Indian, won the 25-mile Road Race Championship at Savannah on April 26, in the new world record time of 21:56. The 50-mile title went to Gene Walker. Indian, in 40:01. also a record.

On the famous old Ascot mile track in Los Angeles, "Shrimp" Burns had gunned his Indian past Otto Walker, Bill Church, and Fred Ludlow on Harleys. Joe Wolters and J. A. McNeil, Excelsior; and Bob Newman, Indian, for a 25-mile track championship at a sizzling 80.89 mph average that w'as faster than the auto record there — so the Indian riders had the sprint titles well nailed down.

The big teams had an advantage in the long grinds, though, and at the 1920 Dodge City 300-mile marathon seven of the 21 entries were Harley-Davidson’s new pocket valve race jobs, and one of the seven w'as ridden by another thunderbike immortal, the great Jim Davis, who starred on both Indians and Harleys on the roads, the dirt tracks, and the great auto speedways for many years.

Gene Walker and "Shrimp” Burns were ready to give him an argument, and Walker had the lead for the first 31 miles until a pit stop lost it for him temporarily. Davis went into the lead at 144 miles, but it was a see-saw affair with Maldwyn Jones, also on a Harley, for most of the race. Jones put up a new 100-mile record of 1:11:12.2. and a 200 of 2:26.48; but it was Jim Davis in at the finish in a record time of 3:40:04.8, and an 81.80 mph average. Gene Walker, Indian, was second, and “Shrimp" Burns added a few laurels for Indian by turning the fastest lap at 94 miles per hour.

Probably the greatest solo performance in motorcycle history was scored in 1921 by Ralph Hepburn, on a Harley, when he won the big race all by himself. He set world’s records all the way with no competition and was 12 miles ahead of his nearest competitor at the finish. He ran up a 100-mile mark of 1:07.54; a 200-mile record of 2:17.54; and a 300 world mark of 3:30.03, with a smashing 85.7 mph average. This terrific one-man achievement by Hepburn climaxed the Dodge City series, and the next 300-mile championship was held at Wichita. Kansas in 1922, with Hepburn then riding an Indian, repeating his triumph but at a much slower time.

In 1923, a 200-mile National was won at Wichita, on July 4th. by Curley Fredericks, on an Indian, at a rapid 2:27.48; but by this time road racing was waning, both for the autos and the bikes. The scene was shifting to closed circuit events, and shorter races on the dirt tracks, and the great circuit of 1 Vi and 2-mile auto speedways.

The motorbikes were born on the boards and they returned to the big tracks where they burned the banks at speeds close to two miles a minute, again rivaling the autos on their own ground in the 1920’s; but whether on the roaring roads or the “suicide saucers,” those old 61-inch Indians, Harleys, and Excelsiors were one good reason they called them "the roaring twenties.” •