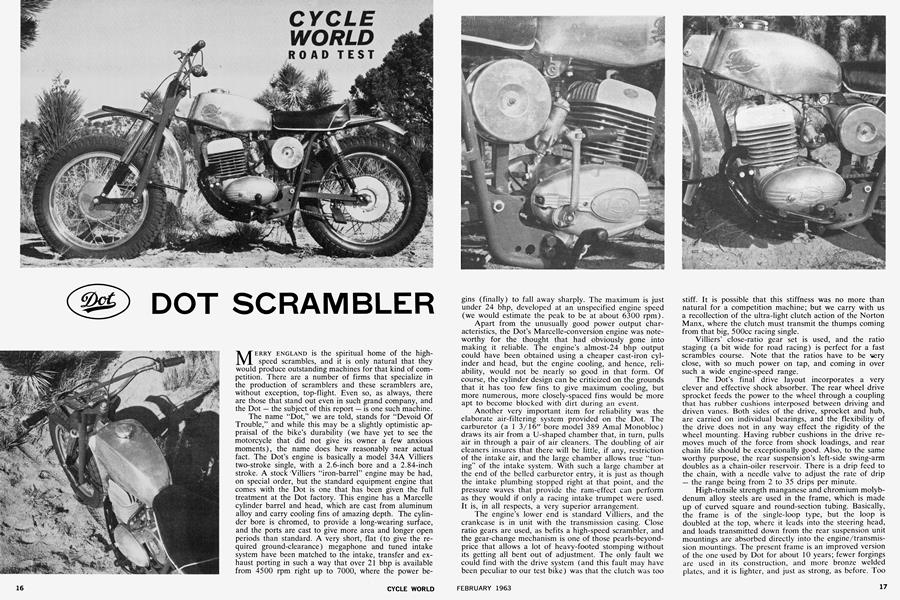

DOT SCRAMBLER

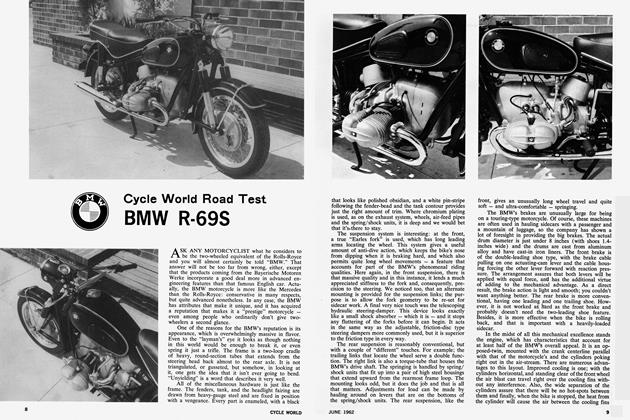

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

MERRY ENGLAND is the spiritual home of the highspeed scrambles, and it is only natural that they would produce outstanding machines for that kind of competition. There are a number of firms that specialize in the production of scramblers and these scramblers are, without exception, top-flight. Even so, as always, there are those that stand out even in such grand company, and the Dot - the subject of this report - is one such machine.

The name "Dot," we are told, stands for "Devoid Of Trouble," and while this may be a slightly optimistic appraisal of the bike's durability (we have yet to see the motorcycle that did not give its owner a few anxious moments), the name does hew reasonably near actual fact. The Dot's engine is basically a model 34A Villiers two-stroke single, with a 2.6-inch bore and a 2.84-inch stroke. A stock Villiers "iron-barrel" engine may be had, on special order, but the standard equipment engine that comes with the Dot is one that has been given the full treatment at the Dot factory. This engine has a Marcelle cylinder barrel and head, which are cast from aluminum alloy and carry cooling fins of amazing depth. The cylinder bore is chromed, to provide a long-wearing surface, and the ports are cast to give more area and longer open periods than standard. A very short, flat (to give the required ground-clearance) megaphone and tuned intake system have been matched to the intake, transfer and exhaust porting in such a way that over 21 bhp is available from 4500 rpm right up to 7000, where the power begins (finally) to fall away sharply. The maximum is just under 24 bhp, developed at an unspecified engine speed (we would estimate the peak to be at about 6300 rpm).

Apart from the unusually good power output characteristics, the Dot's Marcelle-conversion engine was noteworthy for the thought that had obviously gone into making it reliable. The engine's almost-24 bhp output could have been obtained using a cheaper cast-iron cylinder and head, but the engine cooling, and hence, reliability, would not be nearly so good in that form. Of course, the cylinder design can be criticized on the grounds that it has too few fins to give maximum cooling, but more numerous, more closely-spaced fins would be more apt to become blocked with dirt during an event.

Another very important item for reliability was the elaborate air-filtering system provided on the Dot. The carburetor (a 1 3/16" bore model 389 Amal Monobloc) draws its air from a U-shaped chamber that, in turn, pulls air in through a pair of air cleaners. The doubling of air cleaners insures that there will be little, if any, restriction of the intake air, and the large chamber allows true "tuning" of the intake system. With such a large chamber at the end of the belled carburetor entry, it is just as though the intake plumbing stopped right at that point, and the pressure waves that provide the ram-effect can perform as they would if only a racing intake trumpet were used. It is, in all respects, a very superior arrangement.

The engine's lower end is standard Villiers, and the crankcase is in unit with the transmission casing. Close ratio gears are used, as befits a high-speed scrambler, and the gear-change mechanism is one of those pearls-beyondprice that allows a lot of heavy-footed stomping without its getting all bent out of adjustment. The only fault we could find with the drive system (and this fault may have been peculiar to our test bike) was that the clutch was too

stiff. It is possible that this stiffness was no more than natural for a competition machine; but we carry with us a recollection of the ultra-light clutch action of the Norton Manx, where the clutch must transmit the thumps coming from that big, 500cc racing single.

Villiers' close-ratio gear set is used, and the ratio staging (a bit wide for road racing) is perfect for a fast scrambles course. Note that the ratios have to be \*ery close, with so much power on tap, and coming in over such a wide engine-speed range.

The Dot's final drive layout incorporates a very clever and effective shock absorber. The rear wheel drive sprocket feeds the power to the wheel through a coupling that has rubber cushions interposed between driving and driven vanes. Both sides of the drive, sprocket and hub, are carried on individual bearings, and the flexibility of the drive does not in any way effect the rigidity of the wheel mounting. Having rubber cushions in the drive removes much of the force from shock loadings, and rear chain life should be exceptionally good. Also, to the same worthy purpose, the rear suspension's left-side swing-arm doubles as a chain-oiler reservoir. There is a drip feed to the chain, with a needle valve to adjust the rate of drip — the range being from 2 to 35 drips per minute.

High-tensile strength manganese and chromium molybdenum alloy steels are used in the frame, which is made up of curved square and round-section tubing. Basically, the frame is of the single-loop type, but the loop is doubled at the top, where it leads into the steering head, and loads transmitted down from the rear suspension unit mountings are absorbed directly into the engine/transmission mountings. The present frame is an improved version of the one-used by Dot for about 10 years; fewer forgings are used in its construction, and more bronze welded plates, and it is lighter, and just as strong, as before. Too many tubes are subjected to bending loads for this to be termed a very efficient design, but it is tremendously rugged, and in the long run that is probably more important.

Swing arms are used for both the front and rear suspensions, with outstanding results in both instances. The layout at the rear is much like that seen on many another motorcycle, with the exception of a rather clever longreach adjustment for the wheel. This is to accommodate the chain-length variations that come with the wide selection of sprockets that are available for the Dot. Also, the rear suspension is noteworthy for the manner in which proper and continued wheel alignment is insured. All of the compressive loads from the drive are fed directly to the transmission casing (because the rear swing arm actually pivots from the transmission mounting plates).

Early versions of this model Dot had a front suspension that transmitted braking torque into the leading arms; now, a separate link leads from the forks to the brake backing plate. Without the link, braking torque would have a tendency to lift the front of the machine, and make the suspension behave .peculiarly. Good use has been made of this lifting effect on some road machines, but out in the rough, where things may not be any too steady anyway, the suspension gains from having been "neutralized."

Light aluminum alloy is used in the Dot's fenders, number-plates and fuel tank. This last item is both practical and attractive, having a stylish square shape that gives a maximum of unobstructed steering lock and a tapered underside to direct air down at the cylinder head. The competition-oriented nature of the Dot is made all the more apparent by the fact that this tank is unpainted (the bright aluminum finish looks pretty good) and has a racing quick-release filler cap. The tank capacity is 2lA imperial (2.7 U.S.) gallons.

More light alloy is used in the Dot's wheels and brakes, and there can be no doubt that unspring weight has been held to a minimum. The Boranni alloy wheels are, as the bike is delivered, shod with knobby tires, but our test machine had been equipped with a sort of "trialsuniversal" Pirelli. These had a block-tread that was not much in deep sand, but on a medium-hard surface they could not be beaten. This same tire is currently a big favorite among the flat-track exponents.

It may sound strange to describe a competition bike like the Dot as "comfortable," but comfortable it was. The seat is soft and wide, the pegs are well placed and the handlebars have a nice reach and give excellent leverage. More important, the bike is carried along on a suspension system that is as good as any we have ever tried. Slathers of wheel travel have been provided, and the springing and damping is perfect. At various points during the test, we tried the bike over many different types of terrain, and not even during some soaring jumps did the suspension bottom. The Dot would leap into the air like a gazelle, and land in just as surefooted a fashion.

Cornering was outstanding, too. The tires may have helped, but for whatever reason, we found that the Dot could be dropped over and powered through the bends in a grand manner. Here, the wide power band of the engine is a real blessing; it is natural for a bike to bog down a bit right at the apex of a turn (at least they do the way we take them) and it is a great help to be able to turn on the tap and have all of that urge right there. And too, the Dot (unlike some bikes with long-travel suspension) was stable enough to allow a lot of throttle-steering when it was heeled well over.

For sheer power and speed, the Dot we were given for test had it over almost any 250 scrambler available. However, our test machine had been tuned for, and was running on, a potent brew that was a far cry from the usual pump gasoline. For that reason, the performance obtained cannot fairly be compared with any of the other 250s we have tested. The Dot's engine is basically the same as other breathed-upon Villiers units, however, and its straight-line performance should be substantially identical to all other modified-Villiers powered scramblers running on the same fuel.

The only complaints on our staff voiced about the Dot was that it was excruciatingly noisy (as are all of its major competitors), and that it is a smidgin too fussy for ordinary cross-country sports use; and neither of these complaints are really valid. The Dot is a racing bike, pure and simple, and for that purpose it is at the very top of its particular heap. There may be others that are better; no one on our staff is really good enough in the dirt, at high speeds, to say which of the top 250 scramblers is definitely the best. Suffice to say that we could find no fault with either its handling, finish, or speed. Only the evidence furnished by race results is going to settle this question. •

DOT 250 SCRAMBLER

$795.00

SPECI FICATIONS

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue