COTTON COUGAR

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

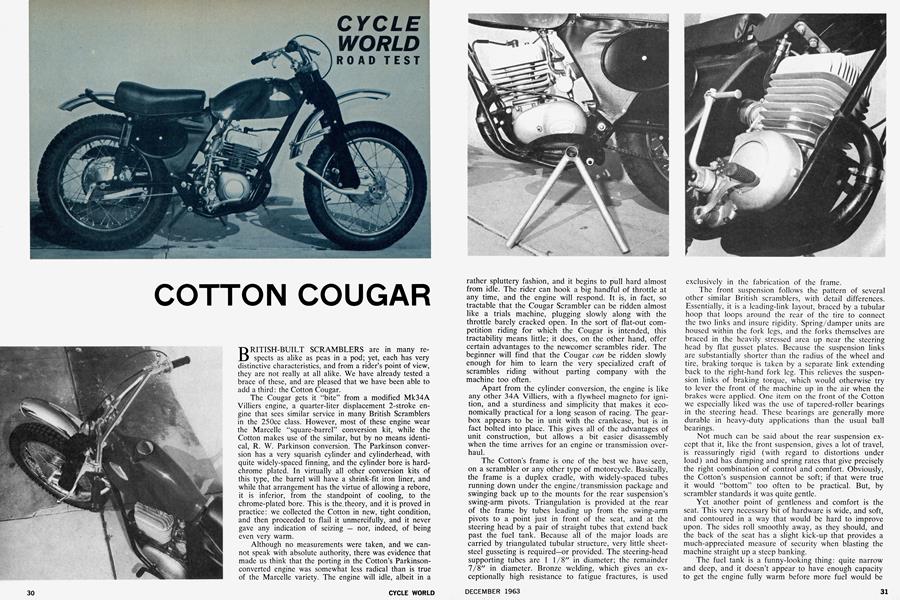

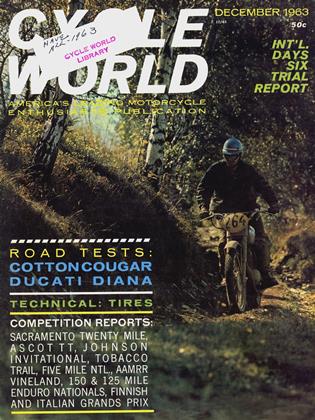

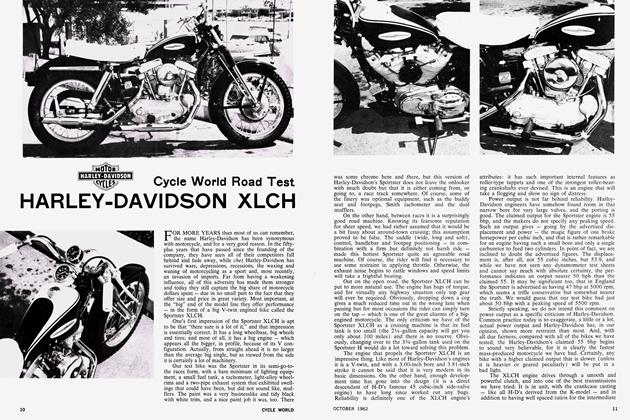

BRITISH-BUILT SCRAMBLERS are in many respects as alike as peas in a pod; yet, each has very distinctive characteristics, and from a rider's point of view, they are not really at all alike. We have already tested a brace of these, and are pleased that we have been able to add a third: the Cotton Cougar. The Cougar gets it "bite" from a modified Mk34A Villiers engine, a quarter-liter displacement 2-stroke engine that sees similar service in many British Scramblers in the 250cc class. However, most of these engine wear the Marcelle "square-barrel" conversion kit, while the Cotton makes use of the similar, but by no means identical, R. W. Parkinson conversion. The Parkinson conversion has a very squarish cylinder and cylinderhead, with quite widely-spaced finning, and the cylinder bore is hardchrome plated. In virtually all other conversion kits of this type, the barrel will have a shrink-fit iron liner, and while that arrangement has the virtue of allowing a rebore, it is inferior, from the standpoint of cooling, to the chrome-plated bore. This is the, theory, and it is proved in practice: we collected the Cotton in new, tight condition, and then proceeded to flail it unmercifully, and it never gave any indication of seizing - nor, indeed, of being even very warm. Although no measurements were taken, and we cannot speak with absolute authority, there was evidence that made us think that the porting in the Cotton's Parkinsonconverted engine was somewhat less radical than is true of the Marcelle variety. The engine will idle, albeit in a rather spluttery fashion, and it begins to pull hard almost from idle. The rider can hook a big handful of throttle at any time, and the engine will respond. It is, in fact, so tractable that the Cougar Scrambler can be ridden almost like a trials machine, plugging slowly along with the throttle barely cracked open. In the sort of flat-out competition riding for which the Cougar is intended, this tractability means little; it does, on the other hand, offer certain advantages to the newcomer scrambles rider. The beginner will find that the Cougar can be ridden slowly enough for him to learn the very specialized craft of scrambles riding without parting company with the machine too often.

Apart from the cylinder conversion, the engine is like any other 34A Villiers, with a flywheel magneto for ignition, and a sturdiness and simplicity that makes it economically practical for a long season of racing. The gearbox appears to be in unit with the crankcase, but is in fact bolted into place. This gives all of the advantages of unit construction, but allows a bit easier disassembly when the time arrives for an engine or transmission overhaul.

The Cotton’s frame is one of the best we have seen, on a scrambler or any other type of motorcycle. Basically, the frame is a duplex cradle, with widely-spaced tubes running down under the engine/transmission package and swinging back up to the mounts for the rear suspension’s swing-arm pivots. Triangulation is provided at the rear of the frame by tubes leading up from the swing-arm pivots to a point just in front of the seat, and at the steering head by a pair of straight tubes that extend back past the fuel tank. Because all of the major loads are carried by triangulated tubular structure, very little sheetsteel gusseting is required—or provided. The steering-head supporting tubes are 1 1/8" in diameter; the remainder 7/8" in diameter. Bronze welding, which gives an exceptionally high resistance to fatigue fractures, is used exclusively in the fabrication of the frame.

The front suspension follows the pattern of several other similar British scramblers, with detail differences. Essentially, it is a leading-link layout, braced by a tubular hoop that loops around the rear of the tire to connect the two links and insure rigidity. Spring/damper units are housed within the fork legs, and the forks themselves are braced in the heavily stressed area up near the steering head by flat gusset plates. Because the suspension links are substantially shorter than the radius of the wheel and tire, braking torque is taken by a separate link extending back to the right-hand fork leg. This relieves the suspension links of braking torque, which would otherwise try to lever the front of the machine up in the air when the brakes were applied. One item on the front of the Cotton we especially liked was the use of tapered-roller bearings in the steering head. These bearings are generally more durable in heavy-duty applications than the usual ball bearings.

Not much can be said about the rear suspension except that it, like the front suspension, gives a lot of travel, is reassuringly rigid (with regard to distortions under load) and has damping and spring rates that give precisely the right combination of control and comfort. Obviously, the Cotton’s suspension cannot be soft; if that were true it would “bottom” too often to be practical. But, by scrambler standards it was quite gentle.

Yet another point of gentleness and comfort is the seat. This very necessary bit of hardware is wide, and soft, and contoured in a way that would be hard to improve upon. The sides roll smoothly away, as they should, and the back of the seat has a slight kick-up that provides a much-appreciated measure of security when blasting the machine straight up a steep banking.

The fuel tank is a funny-looking thing: quite narrow and deep, and it doesn’t appear to have enough capacity to get the engine fully warm before more fuel would be needed. Appearances are deceiving. The tank holds 1.5 gallons, which is entirely adequate — especially since the engine, for some reason, gives uncommonly-good fuel economy. The tank is made of fiberglass, with the color bonded in, and is mounted on rubber to reduce the possibility of vibration-caused fractures.

Though our test model was not so blessed, future Cougars will mount side stands and a tuned exhaust system, for trailing and the other more gentle pastimes, that takes much of the bite out of the exhaust bark, albeit wth a slight loss of power. Full lighting equipment is also scheduled to be a low-priced optional extra.

Light-alloy fenders have become almost a sine qua non for competition machines, and we were a bit surprised to find that those on the Cotton were of steel. Before you Sneer, consider that it is chrome plated steel, of a relatively heavy gauge, and is scratch-proof and bend resistant. And, further, consider that the Cotton, steel fenders and all, is one of the lightest scramblers available.

Being light, and having a lot of wide-range power, the Cotton naturally performs well, and, we are pleased to report, its handling is equal to the performance. A trio of our staff members, having varying degrees of competence in scrambles-type riding, spent a lot of time out in the rough stuff chasing their own shadows and generally having a grand time, and they were unanimous in praising the Cotton. It is quick enough in its steering to permit the expert the full exercise of his talents; and yet stable enough to indulge the tyro in a few of the inevitable mistakes. And, as we have already said, its suspension has the proper degree of softness, and enough travel, to absorb a lot of pounding without affecting control.

The positioning of the seating, foot-pegs, handlebars and controls was also quite good. The rider can stand on the pegs and still have the bars (which are wide enough to provide the necessary leverage) high enough, relative to his shoulders, to allow excellent control. The pegs are of the non-folding type, and long enough to give a secure footing — they even have their ends turned up to reduce the possibility of a slip.

The only handling problem encountered was the Cotton’s tendency to flap its front wheel from side to side when pressed just beyond the limit on rough ground. This never produced anything more serious than an unexpected and not entirely welcome thrill for the rider, and it is not as worrysome as the constant front-wheel snaking that is a characteristic of another highly-regarded and race-winning British scrambler.

Starting a speed-tuned 2-stroke is always a neat trick, and the Cotton, like all the rest, has its moments, but it did behave a trifle better than most. There was the usual 2-stroke starting drill of turning fuel taps on and off, and pumping furiously at the kick-start lever, and the inevitable business of leaning the machine far over after the engine started so that the fuel in the float chamber would not be carried into the engine while the crankcase was clearing. As in all things, practic makes perfect, and after one learns the “combination,” the Cotton will come to life without too much prodding.

Despite its faults, which are few, and in recognition of its virtues, which are many, we would rate the Cotton as being among the very best of the world’s scrambler motorcycles. It performs well, and has an overall standard of fit and finish that is quite exceptional. If The Cotton Cougar does not carry its buyer up among the front runners in whatever scrambles race in which it is entered, it will not be the machine’s fault. •

COTTON COUGAR

SPECIFICATION

$795

PERFORMANCE

SPEEDOMETER ERROR

POWER TRANSMISSION

DIMENSION, IN.

ACCELERATION