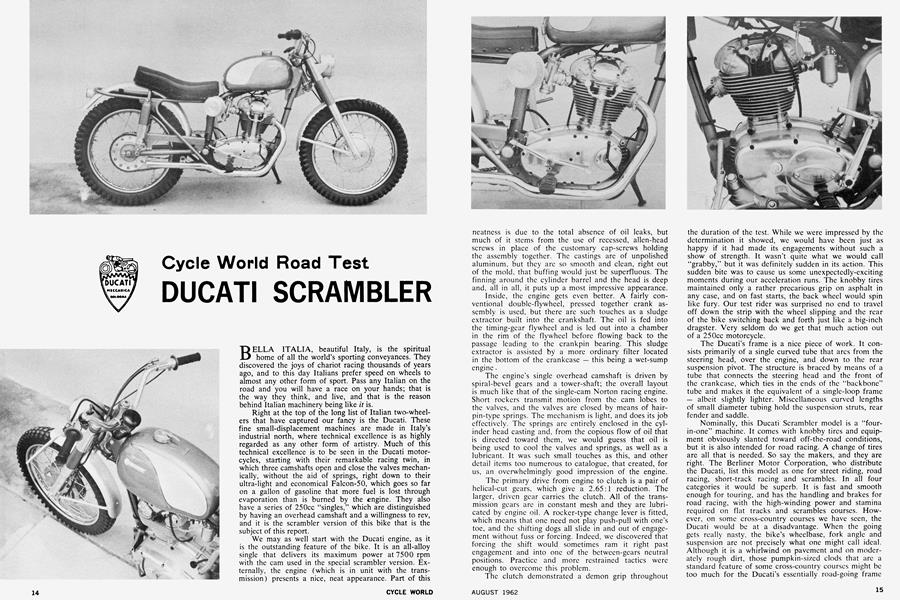

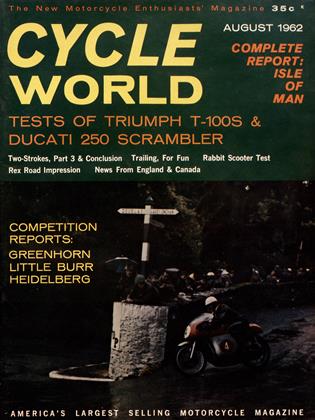

DUCATI SCRAMBLER

Cycle World Road Test

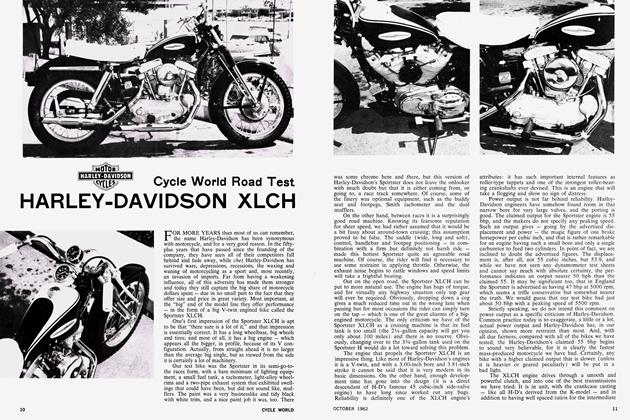

BELLA ITALIA, beautiful Italy, is the spiritual home of all the world’s sporting conveyances. They discovered the joys of chariot racing thousands of years ago, and to this day Italians prefer speed on wheels to almost any other form of sport. Pass any Italian on the road and you will have a race on your hands; that is the way they think, and live, and that is the reason behind Italian machinery being like it is.

Right at the top of the long list of Italian two-wheelers that have captured our fancy is the Ducati. These fine small-displacement machines are made in Italy’s industrial north, where technical excellence is as highly regarded as any other form of artistry. Much of this technical excellence is to be seen in the Ducati motorcycles, starting with their remarkable racing twin, in which three camshafts open and close the valves mechanically, without the aid of springs, right down to their ultra-light and economical Falcon-50, which goes so far on a gallon of gasoline that more fuel is lost through evaporation than is burned by the engine. They also have a series of 250cc “singles,” which are distinguished by having an overhead camshaft and a willingness to rev, and it is the scrambler version of this bike that is the subject of this report.

We may as well start with the Ducati engine, as it is the outstanding feature of the bike. It is an all-alloy single that delivers its maximum power at 7500 rpm with the cam used in the special scrambler version. Externally, the engine (which is in unit with the transmission) presents a nice, neat appearance. Part of this neatness is due to the total absence of oil leaks, but much of it stems from the use of recessed, alien-head screws in place of the customary cap-screws holding the assembly together. The castings are of unpolished aluminum, but they are so smooth and clean, right out of the mold, that buffing would just be superfluous. The finning around the cylinder barrel and the head is deep and, all in all, it puts up a most impressive appearance.

Inside, the engine gets even better. A fairly conventional double-flywheel, pressed together crank assembly is used, but there are such touches as a sludge extractor built into the crankshaft. The oil is fed into the timing-gear flywheel and is led out into a chamber in the rim of the flywheel before flowing back to the passage leading to the crankpin bearing. This sludge extractor is assisted by a more ordinary filter located in the bottom of the crankcase — this being a wet-sump engine.

The engine’s single overhead camshaft is driven by spiral-bevel gears and a tower-shaft; the overall layout is much like that of the single-cam Norton racing engine. Short rockers transmit motion from the cam lobes to the valves, and the valves are closed by means of hairpin-type springs. The mechanism is light, and does its job effectively. The springs arc entirely enclosed in the cylinder head casting and, from the copious flow of oil that is directed toward them, we would guess that oil is being used to cool the valves and springs, as well as a lubricant. It was such small touches as this, and other detail items too numerous to catalogue, that created, for us, an overwhelmingly good impression of the engine.

The primary drive from engine to clutch is a pair of helical-cut gears, which give a 2.65:1 reduction. The larger, driven gear carries the clutch. All of the transmission gears are in constant mesh and they are lubricated by engine oil. A rocker-type change lever is fitted, which means that one need not play push-pull with one’s toe, and the shifting dogs all slide in and out of engagement without fuss or forcing. Indeed, we discovered that forcing the shift would sometimes ram it right past engagement and into one of the between-gears neutral positions. Practice and more restrained tactics were enough to overcome this problem.

The clutch demonstrated a demon grip throughout the duration of the test. While we were impressed by the determination it showed, we would have been just as happy if it had made its engagements without such a show of strength. It wasn’t quite what we would call “grabby,” but it was definitely sudden in its action. This sudden bite was to cause us some unexpectedly-exciting moments during our acceleration runs. The knobby tires maintained only a rather precarious grip on asphalt in any case, and on fast starts, the back wheel would spin like fury. Our test rider was surprised no end to travel off down the strip with the wheel slipping and the rear of the bike switching back and forth just like a big-inch dragster. Very seldom do we get that much action out of a 250cc motorcycle.

The Ducati’s frame is a nice piece of work. It consists primarily of a single curved tube that arcs from the steering head, over the engine, and down to the rear suspension pivot. The structure is braced by means of a tube that connects the steering head and the front of the crankcase, which ties in the ends of the “backbone” tube and makes it the equivalent of a single-loop frame — albeit slightly lighter. Miscellaneous curved lengths of small diameter tubing hold the suspension struts, rear fender and saddle.

Nominally, this Ducati Scrambler model is a “fourin-one” machine. It comes with knobby tires and equipment obviously slanted toward off-the-road conditions, but it is also intended for road racing. A change of tires are all that is needed. So say the makers, and they are right. The Berliner Motor Corporation, who distribute the Ducati, list this model as one for street riding, road racing, short-track racing and scrambles. In all four categories it would be superb. It is fast and smooth enough for touring, and has the handling and brakes for road racing, with the high-winding power and stamina required on flat tracks and scrambles courses. However, on some cross-country courses we have seen, the Ducati would be at a disadvantage. When the going gets really nasty, the bike’s wheelbase, fork angle and suspension are not precisely what one might call ideal. Although it is a whirlwind on pavement and on moderately rough dirt, those pumpkin-sized clods that arc a standard feature of some cross-country courses might be too much for the Ducati’s essentially road-going frame and forks. This does not, of course, reflect unfavorably on the Ducati's overall performance. On the contrary, it is astonishing that it will do such a wide variety of things so well. Its deficiencies in rough terrain simply reflect the fact that no bike will do everything equally well.

Starting these small, high-compression singles can be a real chore, and we were pleasantly surprised to find that the Ducati would come to life with very little urging. The ignition has an automatic spark advance, which keeps the engine from biting back, and the engine proved to be a one-kick starter once it was warm. From cold, a trifle more effort was required, but not enough to tire us.

The brakes were obviously intended for road-racing, as they are very large, with finned aluminum drums, and air-scoops and vents cast into the front backing-plate. With so much brake area, and the speed of our test bike limited so severely by its gearing, we never managed to work them hard enough to get them warm — much less produce any fade. Furthermore, we haven’t heard any complaints about their effectiveness from the men who are road-racing Ducatis, and winning.

Appeal of the Ducati Scrambler is further enhanced by the lavish selection of gears and extras that are available. They include: a full set of control cables, valve adjustment caps, a pair of rigid frame members to replace the rear shocks for use on a flat track, tachometer drive unit, three extra rear sprockets (45, 50 and 60 tooth), and an extra 16 tooth countershaft sprocket. By the simple expedient of experimenting with this huge selection of ratios one can either push the top speed up to 100 mph, employ a strain-free overdrive, or set up for maximum (and a bit shattering) acceleration.

Our test machine was equipped with the standard 55 tooth rear sprocket and 14 tooth countershaft sprocket, both of which are somewhat of a compromise yet offer amazing performance for a 15 cubic inch cycle.

The finish on this Ducati scrambler is extremely good. Parts are made with obvious care, and fitted with precision. The paint was much more restrained in color than any previous Ducatis we had seen, being a light pearlescent blue, and we thought it looked great. Whatever its short-comings out in Farmer John’s plowed “south-forty,” it more than compensates for this with its speed and handling every place else. If you are in the market for a 250, even a cross-country bike (you can always juggle the fork angle), don’t miss this one. •

DUCATI 250 SCRAMBLER

$669