ORIGINAL LUXURY

The Honda Gold Wing changed touring in America—and the world—forever

March 1 2022 KEVIN CAMERONThe Honda Gold Wing changed touring in America—and the world—forever

March 1 2022 KEVIN CAMERONORIGINAL LUXURY

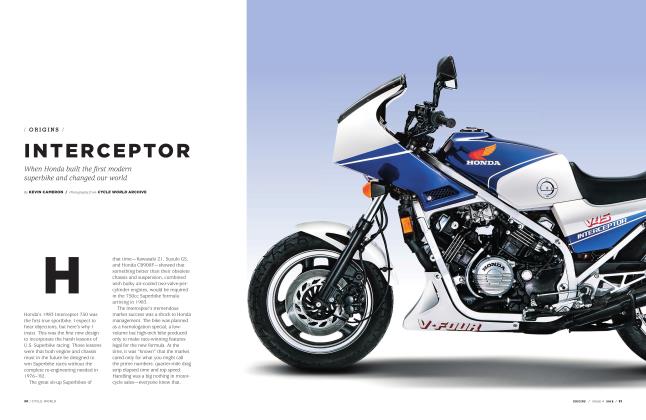

ORIGINS

The Honda Gold Wing changed touring in America—and the world—forever

KEVIN CAMERON

Gold Wing is the motorcycle that originally defined the luxury touring market segment. The curious fact is that despite being originally planned as a refined high-performance motorcycle, it evolved into a touring machine at the urging of American riders who saw its other possibilities. Its development was a real collaboration between the manufacturer and the users.

Although a lot was simmering on Honda’s stovetop in the 1970s, in the marketplace its products were middle-of-the-road—appropriate for the company that was then to motorcycling what General Motors was to automobiles. The concept of a dedicated, technically oriented luxury touring motorcycle had yet to emerge.

Honda has always been willing to try the unconventional, even if it doesn’t succeed—think of Valkyrie Rune, or the hydrostatic-drive scooterlike DN-01. Think also of the oval-piston NR500 GP bike. If it’s true that there’s more to be learned from failure than from success, a willingness to fail might unlock doors no one else could see.

Such a door was Honda’s Project 371 in 1972. Its goal was to develop a “king of kings” motorcycle, one that would effortlessly achieve heights of refined performance not previously attempted. No one at the time imagined anything like today’s luxurious and long-legged GL1800.

Project leader would be 32-yearold Shoichiro Irimajiri, the blue-skies engineer who at age 24 had designed Honda’s legendary 250/297cc six-cylinder roadracer, on which Mike Hailwood won three world titles.

The Project 371 prototype was powered by a flat-six, but although it was photographed with streamlined luggage, it’s clear from the nature of that engine’s power, and of the flat-4 engines that entered production in late 1974, that its underlying goal was civilized high performance. Quarter-mile elapsed time—deemed an essential marketing tool at the time—was quicker than for Honda’s original superbike, the CB750, introduced in 1 969. This performance was achieved not by high state of tune but by large displacement (1,470cc) and broad, smooth torque. Performance with refinement.

The motorcycle that actually entered production in 1974 had four cylinders and less displacement (999cc, or 61 ci), but made more power: 80 hp at 7,500 rpm. It came equipped with neither fairing nor luggage.

Those who rode long distances saw in the Wing many qualities they had long sought: effortless power, smoothness, lack of vibration, reliability, plus room for a passenger and luggage. The expressed needs of many riders defined a mandate that Honda did not ignore.

In this process the engine’s nature would gradually change to place performance where touring riders needed it most—at highway cruise— and not at higher rpm as in sporting motorcycles. Peak power would shift downward from the original 7,500 rpm of 1975 to the present 5,500.

The three major elements of engine power are displacement, rpm, and stroke-averaged net combustion pressure. Therefore as rpm was steadily reduced to achieve the smoothness users wanted, displacement had to be increased in steps to compensate—from 999cc in 1975-1979 to 1,085 and then to 1,182 in 1 984. In 1984 came the jump from four to six cylinders and 1,520cc (93ci) in the fourth generation. A further step to the present 1,883 (112ci) came in 2001.

Although the first GL1000 was substantial at 584 pounds, it was made manageable by two unique design features: 1) the low center of mass of its engine, whose cylinders were at the same low height above the pavement as its crankshaft, and 2) the movement of the fuel from its traditional place above the engine (now occupied by the engine’s induction system of four Keihin carburetors) to a much lower position under the rider’s seat. These changes away from tradition gave Gold Wings a lighter feel, making them more easily manageable, especially in traffic.

What is refinement? The first element is lack of vibration. Parallel twins and V-twins need balance shafts to become smooth, and even the then-new inline-fours of the 1970s produced buzzy secondary vibration. Gold Wing’s flat-four was inherently smooth without balancers because its pistons canceled each other’s shaking forces by moving in opposite directions. With four power impulses to a twin’s two, the smoothness of its “push” during acceleration (call it “propulsive smoothness”) was twice that of twins, no matter how their cylinders were arranged.

Liquid-cooling, once regarded as too complex and heavy for motorcycles, was required by Gold Wing’s cylinder arrangement—one ahead of the other on either side. Only liquid-cooling could prevent what would otherwise happen—trying to cool the rear cylinders with air already heated by passing through the fins of the cylinders ahead of them. Water-cooling also does away with the “ringing”—sympathetic vibration—of cooling fins. Where air-cooled engines run hotter and richer in summer, cooler and leaner in winter, water-cooling’s thermostat held Gold Wing’s engine at constant temperature year-around, whether the route ran through Death Valley or over mountain passes.

Enclosed shaft drive freed the Gold Wing rider from the task of oiling a drive chain at every refueling. O-ring chain, sealing lubricant in and dirt out, did not then exist, and toothed belts, produced since the early 1940s, had yet to be made strong enough for power transmission.

How does refinement benefit the rider? Lack of vibration makes a long day’s ride into enjoyment rather than survival. The machine does its work without constant intrusion upon the rider’s awareness.

Why did Honda enter the market with a 999cc flat-four rather than continue development of the bigger prototype flat-six? Mr. Honda thought the public might view six cylinders as too complex. Also, their extra length pushed the rider back, away from the bars. Planners were unsure of market response to engines more than 1,000cc. The GL1800 of today makes perfect sense to us, but the machine and its expanding market had to develop together.

As long-distance riders adopted the new Gold Wing, they equipped it for their own purposes, with fairings to provide shelter from wind, with luggage for the necessities of travel.

Stability is essential for long-distance riding because a stable machine is less deflected by road disturbances, relieving the rider of constant corrections. The recipe for stability is to be long and low, with high stability steering geometry—a rake angle of close to 30 degrees and trail over 4 inches.

The first GL had a 60.6-inch wheelbase and the 28-degree steering rake of its time, with the longish trail of 4.7 inches. While sportbikes, seeking quick maneuverability, have arrived around 24 degrees and just under 4 inches of trail, the latest GL1800 is at 29.25 degrees and 4.3 inches.

Essential to precise steering are chassis and fork stiffness, which transmit more of the rider’s control effort to the front wheel, and less into flexing the parts. Gold Wing’s chassis has been stiffened several times to deliver responsive steering despite growing weight.

Why the 1988 switch from flat-four to flat-six? With engine displacement growing but cruising rpm remaining close to 3,000 rpm, the pulsing of bigger cylinders became noticeable, especially at lower speeds. To restore propulsive smoothness, four cylinders had to become six. Most recently, the driveline of GL1800 has been constructed as a bonded rubber torsional damper, further increasing smoothness.

The distance from rider to bars has been reduced in more than one way. Not only have engines been moved forward, they have also been redesigned to make them shorter. In the most recent sixth-generation Gold Wing, a twin A-arm girder fork takes the place for the long-serving telescopies. Its virtue is vertical wheel movement, rather than the up-and-back movement of an inclined telescopic fork. This has made it possible to move the engine forward yet again, providing more room for rider and passenger.

Mr. Honda thought the public might view six cylinders as too complex.

For 2001 engine displacement was boosted again—to 1,832cc. Aluminum chassis had replaced steel in racing in the 1980s, then became the norm for sportbikes in the ’90s. Now the Gold Wing six engine became a stressed member of an all-new aluminum frame. It consisted of two large extruded main beams directly joining the steering-head to the swingarm pivot uprights, with a welded-on twin-loop seat structure above the rear wheel.

Weight has increased as Gold Wings have evolved to provide rider and passenger with greater comfort, security, and convenience through improved seating, wind protection, and the provision of outstanding electronic conveniences. The 584 pounds of the first Wing increased 58 percent to the 928-pound wet weight of the 2018 sixth-gen GL1800. The weight reduction program of the sixth generation (2018) has reset dry weight back to just over 800 pounds. Engine power has risen over the years from 80 hp to 125.

Equipped until recently with five-speed transmissions, GLs in 2018 adopted a choice of a six-speed foot-shift transmission or a seven-speed semi-automatic dual-clutch transmission, also known as DCT .When some riders had difficulty backing bikes out of downhill parking spaces, Honda provided an electric reverser, powered by the starting motor. In this “walking mode” the bike either reverses at 0.75 mph or moves ahead at 1.1 mph (only with DCT).

The sixth-generation GL engine arrived in 2018. Bore and stroke were made equal at 73.0 x 73.0mm = 1,833.2cc and each cylinder has been given four valves. Look at the torque curve delivered by the change to four valves: It’s not a “curve” at all, it is rectangular, giving its peak of 108.4 pound-feet (on the Cycle World dyno) at just 1,210 rpm, and being above 100 pound-feet from 850 rpm to 4,800. The manufacturer’s claimed power at the crankshaft is 125 hp, which on CW’s dyno becomes 98 rear wheel horsepower at 5,550 rpm.

That nearly constant flat torque across a superwide range is something you would expect from an electric motor rather than from an internal combustion engine. Yet here it is, expanding the Gold Wing’s many contributions to motorcycle touring.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

The OWNER

The OWNERTHE SURVIVOR

Issue 2 2022 By ANDREA WILSON -

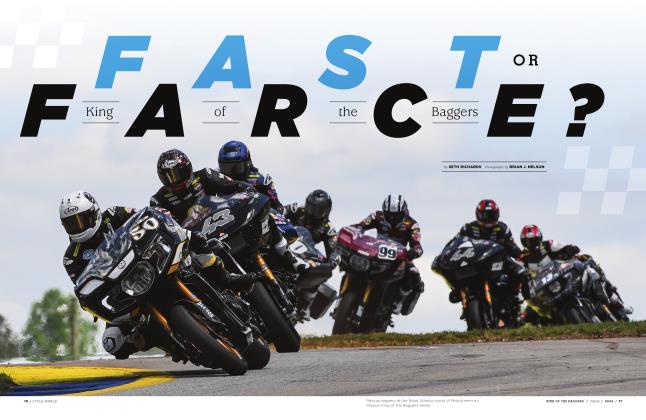

FAST OR FARCE King of the Baggers

Issue 2 2022 By SETH RICHARDS -

ELEMENTS

ELEMENTSCONTROLLED FILL

Issue 2 2022 By KEVIN CAMERON -

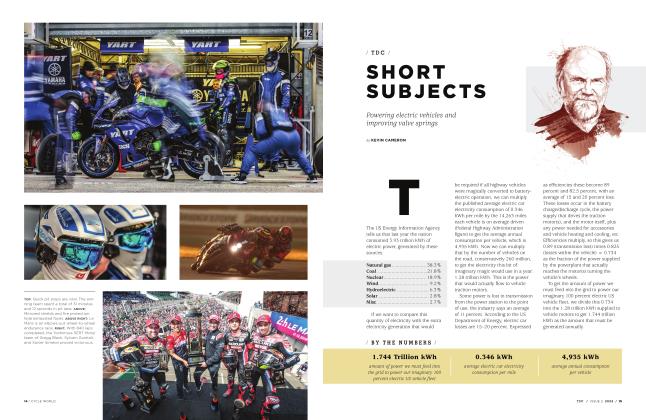

TDC

TDCSHORT SUBJECTS

Issue 2 2022 By KEVIN CAMERON -

UP FRONT

UP FRONTUPSIDES

Issue 2 2022 By MARK HOYER -

PHOTO ESSAY

PHOTO ESSAY24 HEURES MOTOS

Issue 2 2022 By Michael Gilbert