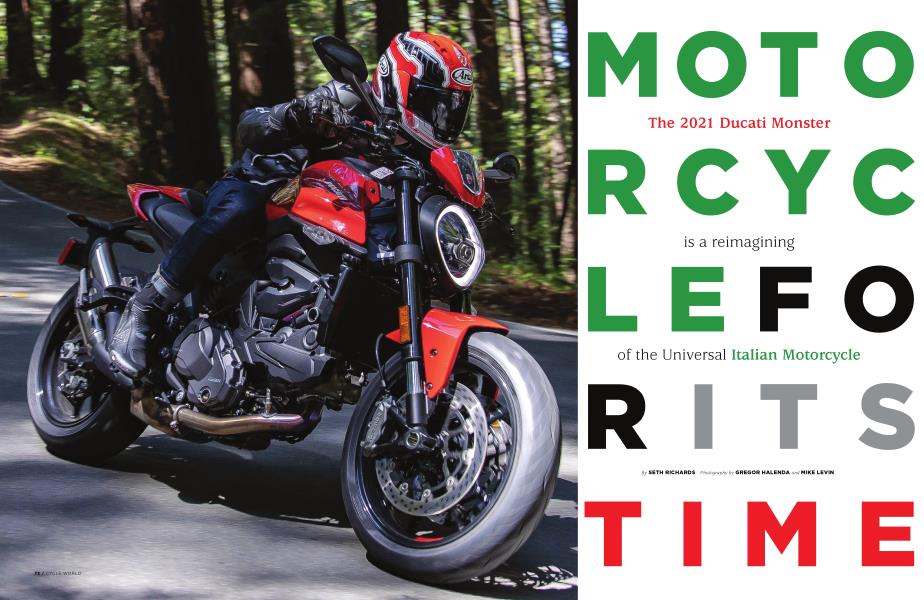

The 2021 Ducati Monster is a reimagining of the Universal Italian Motorcycle

September 1 2021 SETH RICHARDSMOTORCYCLE FOR ITS TIME

The 2021 Ducati Monster is a reimagining of the Universal Italian Motorcycle

SETH RICHARDS

Sometimes a change of scenery can do worlds of good. After a year of homebound same old, same old blah, there’s never been a time when something a bit different is so enticing. Airbnbs are booked solid, the real estate market is in a tizzy, and airports are buzzing with desperate travelers looking to get out of Dodge. Ducati couldn’t have planned this more perfectly even if it tried. For if ever the motorcycle world, with all its conservatism, sentimentality, and nostalgia, was primed to accept a revamped icon, it’s now.

At least, that’s what Ducati is banking on. Because at first glance the 2021 Ducati Monster (MSRP: $11,895) looks like a gamble.

During the US press introduction, Ducati’s marketers attempted to articulate the stylistic threads connecting Miguel Galluzzi’s original icon to the 2021 Monster by pointing out the way the new bike’s circular headlight and “bison back” tank shape resemble the M900’s. Except the new headlight isn’t round, is it? And the tank only looks like the original’s if you shut one eye and squint. So what’s Ducati on about? Is the new Monster still a Monster?

Walking up to the bike, the first thing to impress isn’t the new styling but the diminutive dimensions. The thing is tiny. A large-displacement 90-degree V-twin is by nature less compact than a parallel twin of equal capacity, so the tight packaging and minimalist bodywork make the motor more of a focal point than ever. Between the 32.3-inch seat height, slim saddle, and narrow 3.7-gallon tank, the average rider will have no trouble flat-footing. Accessory low and high seats are available in addition to a lowering kit that brings height down to 30.5 inches.

Traversing the hilly streets of San Francisco, the Monster’s tractable power delivery, light clutch pull, and generous steering lock (which provides seven degrees more handlebar rotation than its predecessor) hint at the Monster’s good manners. More importantly, it’s immediately evident that Ducati changed things up for good reason; 40 good reasons, actually. Weighing a claimed 366 pounds dry/414 pounds wet, the Monster is 40 pounds lighter than its predecessor, the Monster 821. That makes it only 8 pounds heavier than the featherweight Yamaha MT-07. Accordingly, the new Monster feels incredibly light off the sidestand and easy to maneuver around town.

Ducati saved 10 pounds alone from replacing the trellis frame with a Panigale-like aluminum number. Regardless, some entrenched Ducatisti will view the move as sacrilegious. However, it’s worth remembering that the Monster can’t rightly be identified with a single engine or chassis design. Over 28 years, and with more than 350,000 units sold, the Monster has sported Desmodue, Desmoquattro, and Testastretta engines of varying displacements and evolutions. While it’s always had a trellis frame, the 2008 Monster 696 debuted with a short-frame concept that hardly resembled the 851/888 chassis of the original. Then, in 2014, the Monster 1200 debuted with an even shorter frame bolted directly to the cylinder heads in the style of the 1199 Panigale’s monoscocca. Trellis frames are good enough for KTM, you may be thinking; heck, the Austrians use them on their RC16 MotoGP bike, for Pete’s sake. But the fact is, Ducati has moved on. Seven years of aluminum-framed superbikes determined the Monster’s fate long ago.

On the engine front, the 821 mill is replaced by Ducati’s tried-and-true 937cc Testastretta 11 °, as found in the Multistrada 950, SuperSport 950, and Hypermotard 950. In the latter, the engine is tuned to be a raging beast with very immediate throttle response and not-for-thefaint-of-heart low-end grunt. Like Calvin’s killer bicycle in the Calvin and Hobbes comics, one imagines it stalks its owner around the garage corner, ready to pounce as if to prove it’s the alpha in the relationship. In the Monster, the engine’s character is completely transformed to be friendly and accessible, catering to a much broader range of riders. As the Italians would say, it’s buono come il pane, “as good as bread.” Good-natured, friendly.

Power delivery is linear, building progressively to a claimed peak output of 111 hp at 9,250 rpm and peak torque of 69 pound-feet at 6,500 rpm. Output is a modest boost over the 821, but Ducati’s in-house dyno chart shows figures are significantly higher throughout the majority of the rev range. While devoid of the Hyper’s lunacy, the Monster revs freely and has the gumption to lift its front wheel with little prodding. Lugging the motor as low as 2,000 rpm, there’s some expectant shuddering, but dialed-in fueling helps it pull cleanly with none of the electronic stutter steps of some older Ducati ride-by-wire/ EFI systems or driveline lash of even older Ducatis.

In Euro 5 guise, the Monster is unfortunately very muffled, its exhaust note sounding a little too reminiscent of my rototiller. Which, I’ll concede, is also Italian, but not a desmo twin. Such are the times we live in. Fortunately, the airbox makes a compensatory honk above 5,000 rpm.

“Time and place give a design its authenticity. Thus, if design is divorced from contemporary technology it comes across as phony or unoriginal. ”

Ducati refined the Testastretta’s gearbox to make it easier to engage neutral and decrease the likelihood of finding false neutrals between fifth and sixth gears, an issue not uncommon to other 937cc Testastrettas. Shifting is aided by Ducati’s IMU-managed bidirectional quickshifter, which works well in spite of the gearbox’s slight notchiness. Using the quickshifter to downshift from sixth to fifth gear still requires a good bit of force, but at least the false neutrals are absent.

Taking San Francisco’s city streets to the twisting roads through the redwood forests of Skyline Boulevard reveals the best attribute of the Monster’s diet. Its nimble handling at speed makes altering lines midcorner effortless and side-to-side transitions require minimal energy. The Monster’s Kayaba setup is nonadjustable, save preload in the rear, but Ducati did a nice job of finding a setup that’s comfortable for downtown riding and sporty enough for canyon carving. Pavement rippled by the spread of redwood roots beneath the surface presents a challenge, but the Monster doesn’t protest, only occasionally feeling harsh at the bottom of the stroke. Considering many riders are unlikely to fiddle with adjusters anyway, the Kayaba’s basic setup, though evidence of cost-cutting, seems appropriate.

Ultimately, the Monster threads the needle between being accessible and exciting, sensible and sporting, relatable and exotic. Its compact size and light weight give the rider a real sense of command on city streets and on canyon roads. Its tractable motor, full-featured electronic suite, and flattering handling make it a bike that’s easy to like. But is that enough for Monsteristi?

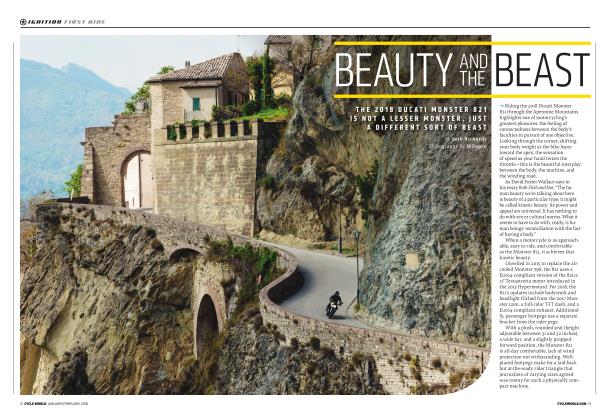

The question is what makes a Monster a Monster? To begin, it’s worth considering the original.

Miguel Galluzzi’s M900 is iconic, in part, because it transcends fashion. It’s timeless. It’s like a blues lick or a Pollock painting: There’s something so pure, so elegantly simple about the original Monster that it seems more born than created, as though it drifted from the heavens to Galluzzi’s pen.

At the same time, the best designs are firmly rooted in time. They seem to embody or in some way express the Zeitgeist of their age. The carefree effervescence of a 1960s Triumph Bonneville will always look like rock ’n’ roll and good times, yet it was a product of a complicated and broken British motorcycle industry that mirrored an outside world that Bonnie-riding hippies wanted so desperately to change. The 1993 Monster is pure Gen X, copping the wadded sportbike aesthetic of the disaffected, too-poor-to-fix-it grunge kid.

Time and place give a design its authenticity. Thus, if design is divorced from contemporary technology, it comes across as phony or unoriginal. In that light, because it prioritizes Ducati’s current technical innovation over tradition, the new Monster is, undoubtedly, a success.

2021 DUCATI MONSTER

$11,895 FOR DUCATI RED

DUCATI.COM

But is it a timeless design? We’ll leave it to you to debate at your local watering hole. It’s certainly more of a departure than previous generations. Little ventured, little gained, as the saying goes. Besides, the Monster has always been defined by more than just its looks.

Remember, the Monster was so named because of its assemblage of parts, not because of its personality. We’re talking Frankenstein’s monster here, not Godzilla.

A Monster isn’t a streetfighter, a supermoto, or a supersport. It’s always been Ducati’s take on the Universal Italian Motorcycle. In the eyes of enthusiasts, it started life as a rational, road-going motorcycle from a race shop that built its reputation on racing glory. In non-motorcyclists’ eyes, it was a fashion statement from the land of Versace and Gucci that became an entry point into Ducati, if not the two-wheeled world at large.

Its design has changed, but the 2021 Ducati Monster is philosophically as true a Monster as ever, an accessible, user-friendly motorcycle that appeals to Ducatisti as much as it does wannabe cognoscenti. As technology advances and much of Ducati’s lineup becomes increasingly focused, powerful, or expensive, the latest iteration is arguably more relevant—more necessary—than ever.

In a year when a change of scenery meant playing the odds, there’s a timely parallel about Ducati’s monster gamble. Now, as the world reopens to a new reality, there’s a new Monster to meet it. The light of a new era shines across its aluminum frame and its not-quite-round headlight, and it can be seen for what it is: a Monster for its time.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

ORIGINS

ORIGINSTALES OF BRAVE ULYSSES

Issue 3 2021 By STEVE ANDERSON -

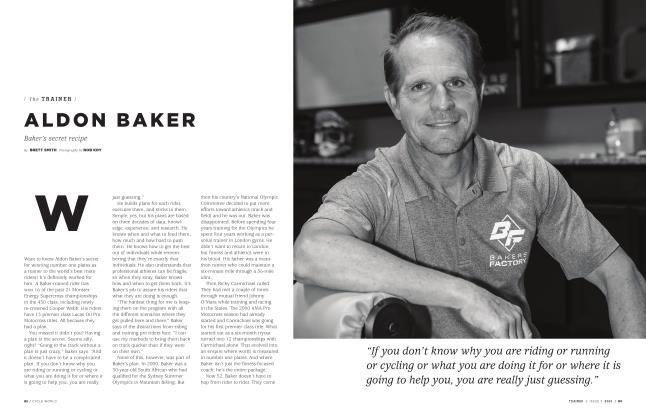

The TRAINER

The TRAINERALDON BAKER

Issue 3 2021 By BRETT SMITH -

CALIFORNIA TT

Issue 3 2021 By MICHAEL GILBERT -

TDC

TDCIN THE STYLE OF THE TIME

Issue 3 2021 By KEVIN CAMERON -

ELEMENTS

ELEMENTSTHE ELEGANT SOLUTIONS

Issue 3 2021 By KEVIN CAMERON -

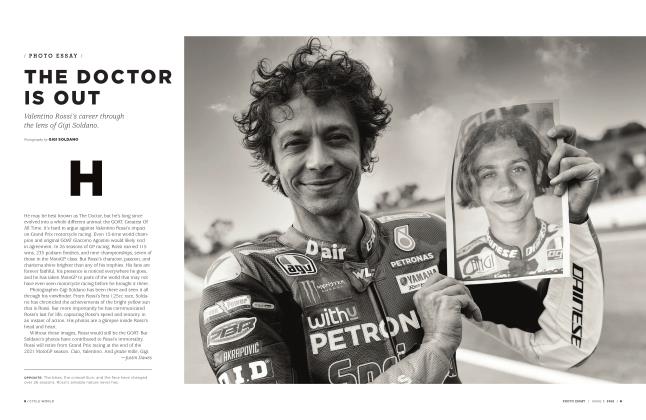

PHOTO ESSAY

PHOTO ESSAYTHE DOCTOR IS OUT

Issue 3 2021 By Justin Dawes