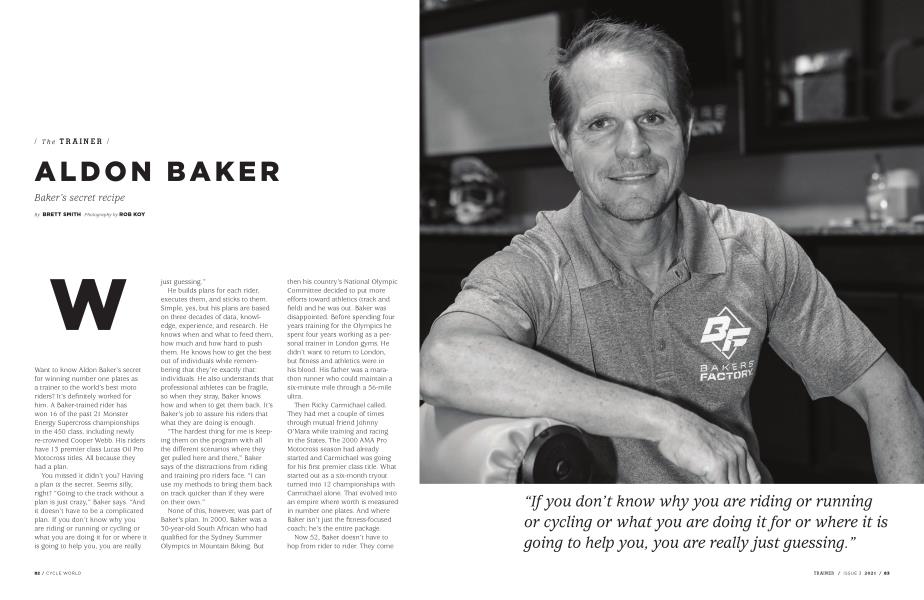

ALDON BAKER

The TRAINER

Baker’s secret recipe

BRETT SMITH

Want to know Aldon Baker’s secret for winning number one plates as a trainer to the world’s best moto riders? It’s definitely worked for him. A Baker-trained rider has won 16 of the past 21 Monster Energy Supercross championships in the 450 class, including newly re-crowned Cooper Webb. His riders have 13 premier class Lucas Oil Pro Motocross titles. All because they had a plan.

You missed it didn’t you? Having a plan is the secret. Seems silly, right? “Going to the track without a plan is just crazy,” Baker says. “And it doesn’t have to be a complicated plan. If you don’t know why you are riding or running or cycling or what you are doing it for or where it is going to help you, you are really just guessing.”

He builds plans for each rider, executes them, and sticks to them. Simple, yes, but his plans are based on three decades of data, knowledge, experience, and research. He knows when and what to feed them, how much and how hard to push them. He knows how to get the best out of individuals while remembering that they’re exactly that: individuals. He also understands that professional athletes can be fragile, so when they stray, Baker knows how and when to get them back. It’s Baker’s job to assure his riders that what they are doing is enough.

“The hardest thing for me is keeping them on the program with all the different scenarios where they get pulled here and there,” Baker says of the distractions from riding and training pro riders face. “I can use my methods to bring them back on track quicker than if they were on their own.”

None of this, however, was part of Baker’s plan. In 2000, Baker was a 30-year-old South African who had qualified for the Sydney Summer Olympics in Mountain Biking. But then his country’s National Olympic Committee decided to put more efforts toward athletics (track and field) and he was out. Baker was disappointed. Before spending four years training for the Olympics he spent four years working as a personal trainer in London gyms. He didn’t want to return to London, but fitness and athletics were in his blood. His father was a marathon runner who could maintain a six-minute mile through a 56-mile ultra.

Then Ricky Carmichael called. They had met a couple of times through mutual friend Johnny O’Mara while training and racing in the States. The 2000 AMA Pro Motocross season had already started and Carmichael was going for his first premier class title. What started out as a six-month tryout turned into 12 championships with Carmichael alone. That evolved into an empire where worth is measured in number one plates. And where Baker isn’t just the fitness-focused coach; he’s the entire package.

Now 52, Baker doesn’t have to hop from rider to rider. They come to him. In June 2014, he plunked down $325,000 to buy 92 acres of raw, Spanish moss-filled land in Center Hill, Florida, and turned it into a literal championship factory with three supercross tracks, two motocross tracks, and more than 10,000 square feet of work/shop/gym/office space between two buildings.

“If you don't know why you are riding or running or cycling or what you are doing it for or where it is going to help you, you are really just guessing. ”

Baker himself maintains a roster of four riders, exclusively from the KTM/Husqvarna Group. He also has a second facility on the same property where understudy trainers work with up to six athletes from the KTM Group network. Those riders pay Baker a lease fee for use of the garage, property, and tracks, and another fee to the trainer. Baker feels like he has a good balance now and a business with a built-in pipeline.

“The benefit to me is that I can bring a rider into my program earlier when I have an opening,” Baker says. Ultimately, he wants to reach the point where he is training and overseeing a group of trainers.

The Bakers’ Factory, as it’s called, (Dream Traxx’s Jason Baker built the tracks) is so legendary now it seems mythical. But Aldon’s core fundamental is as simple as his plans; he builds trust with his riders. He treats every athlete equal but differently.

Baker raised eyebrows when he lumped together four elite riders. Critics told him it wouldn’t work.

But it did. That method got tested in the fall of 2018 when Cooper Webb joined KTM. Webb had prior friction with two riders in the group. Baker doesn’t need his clients to like each other but they must have respect or the program won’t work.

But Webb’s biggest adjustment wasn’t making nice with his new training partners. It was learning to carry the demanded load. “I wasn’t as fit as he thought I was, or even as I thought I was,” Webb says. In Supercross training Webb was three seconds down on lap times. Webb admitted he historically practiced at only 70-80 percent of his max pace and scaled on weekends. That didn’t fly with Baker. When his crew takes the track, the stopwatch runs. Every lap counts. Webb had to adjust to maintain that workload and it resulted in two AMA Supercross championships.

“We’re always evolving with where they are in their career We adapt to preserve. But we don’t let the discipline factor get put away.”

Webb left Bakers’ Factory just before the halfway point of the 2021 pro motocross season for an alternate training facility. Aldon Baker’s program isn’t for everyone. Ken Roczen, Blake Baggett, Jason Anderson, and James Stewart all walked away from Aldon’s program before they retired.

Ryan Dungey, the now retired eight-time AMA MX/SX champ, however, had almost the opposite problem as Webb. He overdid it before joining Baker midway through the 2015 season and deep into the back half of his own career. Dungey said Baker eliminated the doubts and allowed him more time to focus on winning races.

“Nobody else could explain it to me in a manner that made sense,” Dungey says of his search for training rituals. “Aldon also understands regular life issues: mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual.”

“We’re always evolving with where they are in their career,”

Baker says. “We adapt to preserve. But we don’t let the discipline factor get put away. ”

Sounds like a plan.

“When I saw everyone tipping into the pits, I saw an opportunity. I decided I’d rather risk it and crash...

BRAD BINDER

AT THE LIMIT

When a MotoGP race runs with a chance of rain, the drama always seems to ramp up. If the skies decide to open up when the race is underway, there is a mad scramble in the pits as riders jettison their slick-shod machines for ones with soft and sticky rain tires. With four laps remaining at the Bitci Motorrad Grand Prix von Osterreich this was the situation. Six riders were nose to tail approaching the pit entrance. Five entered playing it smart.

KTM’s Brad Binder went for broke.

Binder decided to continue with his KTM RC1 6 on slicks as the rain had not covered the entire circuit— yet. Would the time saved skipping the exchange be enough to cover the gap if the track became cooler and wetter? With two laps to go,

“if” became “when.” Binder had to keep it together on a now-soaked racing surface, cold water sapping heat from his tires and brakes.

“As soon as the rear tire and front tire cooled off, it was like riding on ice,” he said. “And then a couple corners later my carbon brakes went cold, so I had no brakes either.”

He was now a rabbit hunted by the Ducati dogs of Francesco Bagnaia and Jorge Martin, both on warmed tires specifically for wet riding. The gap shrunk rapidly as the two sliced through the pack. In the end the gamble paid off; Binder crossed the line with 12 seconds to spare. As his father has told him many times in his life, “Life favors the brave.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

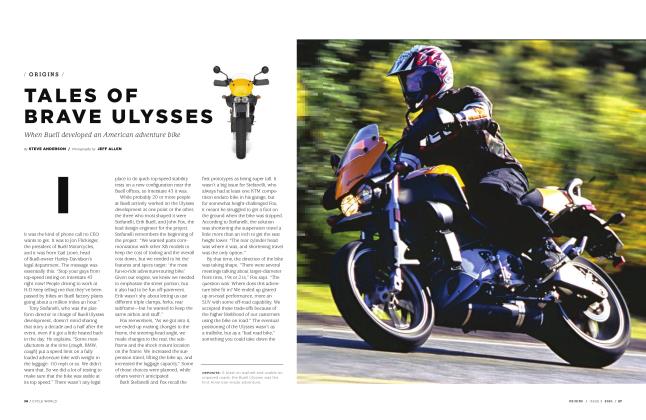

ORIGINS

ORIGINSTALES OF BRAVE ULYSSES

Issue 3 2021 By STEVE ANDERSON -

CALIFORNIA TT

Issue 3 2021 By MICHAEL GILBERT -

TDC

TDCIN THE STYLE OF THE TIME

Issue 3 2021 By KEVIN CAMERON -

ELEMENTS

ELEMENTSTHE ELEGANT SOLUTIONS

Issue 3 2021 By KEVIN CAMERON -

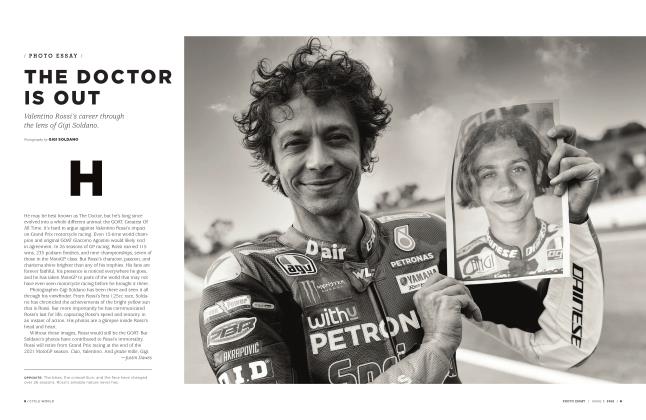

PHOTO ESSAY

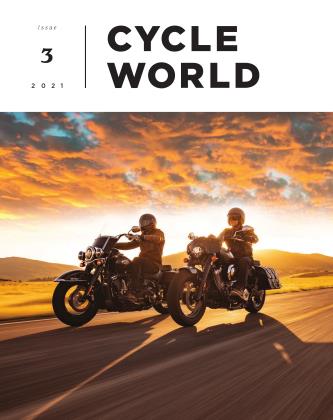

PHOTO ESSAYTHE DOCTOR IS OUT

Issue 3 2021 By Justin Dawes -

UP FRONT

UP FRONTSERIES D

Issue 3 2021 By MARK HOYER