SUPERSTRUCTURE

The strength and elegance of the wire-spoke wheel

March 1 2020 Kevin CameronThe strength and elegance of the wire-spoke wheel

March 1 2020 Kevin CameronSUPERSTRUCTURE

FUNDAMENTALS

The strength and elegance of the wire-spoke wheel

KEVIN CAMERON

The safety bicycle, which exploded into a popular craze around 1895, can be regarded as a confluence of technologies that matured at that time—the ball bearing, pneumatic tire, seamless-drawn steel tubing, roller chain and sprocket drive, and super-strong hard-drawn steel wire. A final ingredient might be the production and shaping of thin metal sheet by rolling.

The last two together made possible one of the most efficient structures known to mechanical engineering: the tension-spoked wire wheel. A roll-formed rim is made by slitting sheet steel into strips, then roll-forming those strips into a wheel-rim section that was finally roll-bent into a circle. The butt ends were joined by brazing or welding.

The wheel hub consisted of a pair of spoke flanges joined by a tube, spinning on the new screwadjustable cone ball bearings, supported on a nonrotating axle.

Rim and flanges were drilled or punched for a suitable number of spokes. The spokes themselves were threaded on their outer ends, and cold-headed and bent on their flange ends. Each spoke is provided with an internally threaded nipple (usually of brass, to prevent rusting to the spoke), which are pushed through dimpled holes in the rim from the OD side, to finally screw onto the spoke ends. The rim material around each spoke hole is dimpled inward to fit the head of the nipple, and each hole is angled to align with the axis of the spoke it will tension.

To assemble a wheel, spokes were threaded through the holes in the two hub flanges, then arranged in the desired pattern (defined by how many other spokes each one crosses). The rim is set in place, and the assembler loosely screws together each spoke and its nipple. Beginners often fall at this first hurdle, but persistence and common sense are rewarded in time.

The process of transforming this loose assembly into a round wheel that is light and strong is an acquired skill that any motivated person can learn, and the result is beautiful in and of itself, much esteemed by custom builders who create endless variations.

Under the tension of the many spokes (36 and 40 were common on motorcycle wheels), the rim is placed in uniform compression that its flanged shape prepares it to support without buckling. Each spoke is a tension spring. A good description of how such a wheel supports loads can be found in Bicycling Science by David Gordon Wilson. He likens this process to that by which a radial tire supports a load. As the tire flattens against the ground, the tension in its thereby slightly less-tensioned nearby carcass fibers (which he likens to spokes) is somewhat reduced, such that the load is supported by a corresponding increase in the fiber tension elsewhere in the tire. It is the great elasticity of the thin wire spokes that makes this work.

Lateral and torsional forces are withstood by angling the spokes. The wheel is braced against lateral forces by spacing the two hub flanges apart to form two “cones of spokes.” Torsional forces are handled by angling the spokes rather than running them straight from hub to rim.

In some cases (a particular Triumph model comes to mind), a wheel might be laced somewhat offset from perfectly centered in relation to its hub. In another case, a bike that turned more easily one way than the other was diagnosed as accidental rim offset.

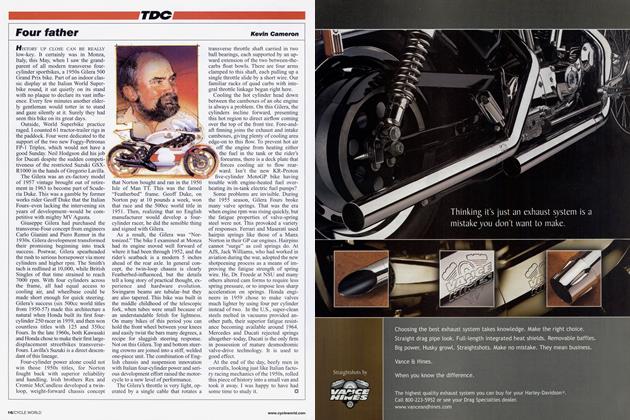

This DID Dirt Star rim and straight-spoke hub are another take on the classic. The angled spoke head necessary to lace to traditional spoke flanges is a source of weakness because it’s loaded in bending. Here, each spoke and its head are perfectly straight, made possible by the fancy angledrilling of the hub in this photo. The result is an especially durable spoked wheel.

Early brake drums and sprocket carriers were bolted to a face of the hub, but as drums grew bigger, it became more sensible to make the spoke flanges as part of the drum itself. Continued growth of brake drums resulted in very short spokes, barely 3 inches long. Because the elastic stretch of which a spoke is capable increases with its length, this loss of “stretchiness” sometimes resulted in wheels whose spokes became loose when the brake drum expanded from the heat of hard use.

The elasticity of wire-spoked wheels can be useful. One Supersport race team tried everything to eliminate chatter from its bike. Success finally came with a wire wheel replacing the stock cast wheel. Marketing replied with a firm no when the team urged that a “heritage model” with wire wheels be offered to make them class-legal.

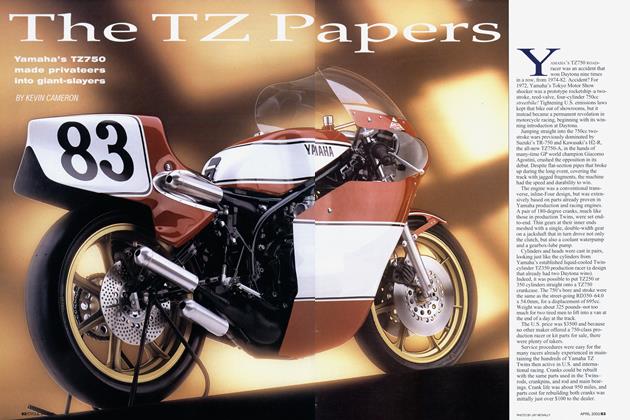

Yamaha’s Daytona-dominating TZ750 (1974~’82) was always delivered on wire wheels, but most racers replaced them with Morris or Shelby-Dowd cast mags. My experience with several riders was that no one complained of any problem if circumstances obliged us to run a wire wheel.

Cast wheels quickly responded to the rapid evolution of motorcycle tires, and in particular made it possible to run tubeless (saving a significant 3 to 5 pounds of rotating weight). Today, cast or forged onepiece wheels have become normal, and wire wheels are often seen as graphic elements for custom builders and manufacturers. But the wire-spoke wheel remains the primary choice for off-road and adventure bikes, which benefit from the strength and resilience of this elegant design.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue