EXPLORING WYOMING'S BACKCOUNTRY ABOARD A TIMBERSLED-EQUIPPED HUSQVARNA FE 501

June 1 2017 Sean MacdonaldRIDING IN THE CLOUDS

EXPLORING WYOMING'S BACKCOUNTRY ABOARD A TIMBERSLED-EQUIPPED HUSQVARNA FE 501

Sean MacDonald

The first thing I learned about riding a Timbersled snowbike is that it is nothing like riding a dirt bike. It may look like a dirt bike (sort of) and sound like a dirt bike, and you may be able to ride it places in winter that you’d normally ride a dirt bike, but a dirt bike it is not.

It’s hard to think of a better place to learn this than riding for two days near Jackson Hole, Wyoming. If carving powder on a 50-hp, 370-pound trackedand-skied off-road bike isn’t on your bucket list, it should be. These were some of the best riding days of my life.

Thankfully, for my first Timbersled experience, I was in the company of Dan Adams and his team from NXT LVL Clinics. My ride was a 2017 Husqvarna FE 501 with the short track Timbersled kit (track length varies from 120 to 137 inches; shorter tracks are better for tighter sections, and longer tracks excel in deeper snow conditions). Adams is a professional snowmobile rider and all-around mountain man, and my education from him started as soon as I thumbed the starter.

“Wait, you gotta get off and walk it across the street,” Adams called out. “The ski has nothing to grip on asphalt, and you’ll pancake if you touch the bars while you try to ride it across. You have to walk it.”

Snowbikes aren’t just bad at crossing the street. They’re miserable on groomed trails too. Unlike a snowmobile, a snowbike doesn’t have the stability provided by a second front ski, so riding on hard-packed snow feels like trying to ride a dirt bike on rutted hardpack that’s been covered in grape jello. Momentum is your friend, but you sort of always have that feeling you get when you’re leaning back in a chair and you start to tip—the thing unpredictably catches edges incessantly.

Once you get to the snowbike version of sand, struggling through the whole terrifying morning begins to make sense. The Timbersled transforms in fresh snow, where its weight and ski stop trying to topple you and start carving into the snow like a sharp knife through a ripe summer peach. The irony here is sand can be the most difficult part of dirt riding. But powder is magic.

Fortunately, learning to ride a snowbike isn’t that hard, and we got the hang of it quickly as we chased each other up the mountain like children playing tag—at least until I tried to pass Chris Sorenson through a set of rollers.

Without the large front wheel to roll over obstacles or dips, a Timbersled is pretty good at sending you over the bars. You hit that front ski wrong and it digs in. The result is something called a “scorpion,” which I experienced repeatedly.

Even more so than with dirt bikes, momentum and brute force are your friends, and target fixation is your mortal enemy. Outside of open desert riding, you’re almost always in someone’s tracks when on a dirt bike—more so when you find yourself riding in an area like the wooded mountains we were in. With snowbikes, the opposite is true because the snow covers most obstacles and ruts, making trees the only real “obstacle.” The bike is designed to carve through fresh snow and struggles once you introduce hard lines (like someone else’s tracks).

You stay on the gas and do your best to avoid looking at the trees as you make your own line up the mountain.

I’d have screamed if I could breathe, but initially it was all too much to process. Between the floating sensation, trees coming at me like TIE fighters, and figuring out how to breathe in a way that didn’t fog my goggles, it was all I could do to keep the thing upright and take in the whole experience.

As I started to understand how to ride snowbikes, I questioned even more who the customer might be. Snowbikes aren’t snowmobile replacements, and they certainly aren’t motorcycles. They’re not cheap, as a decent bike plus Timbersled kit will cost you $15,000 to $20,000.

Lots of us daydream about living somewhere you could buy one bike and convert it for winter so you could ride year-round, but a snowbike demands a powerfully tuned motor (motocrosstype 450s are best) and beefier suspension to handle the additional weight of the kit and the snowbike riding style. According to Adams, most snowbike owners just end up buying two bikes— something like a KTM 450 SX-F or 500 EXC for their conversion and a KTM 350 EXC-F for summer.

So why go through all the trouble and expense? Because it’s incredible. Because you can get to places you’d never be able to see otherwise. Because it’s a sensation unlike anything else you’ll ever experience. Because it’s one you can experience in a way that’s foreign yet completely natural. And because it’s so much fun.

A snowbike is not a dirt bike. It makes things like roads or hardpack or trails—things that you’d expect to be easy—hard and unsettling. It also makes wide-open spaces filled with soft and undefined areas a joy like I’ve never experienced. Snowbikes let you get almost anywhere on a mountain, places you’d never be able to go on a snowmobile or dirt bike. It isn’t better and it isn’t worse; it’s just its own special kind of beautiful, and it allows you to experience both powersports and the world in a completely unique and completely wonderful way.

I’ve recently come to realize that my newfound love for trail riding comes from a different place than my love for street riding. With dirt, it isn’t speed and proficiency I’m chasing as much as it is that next hilltop or another incredible view. Trail riding scratches a desire to explore that my distaste for hiking (or any monotonous and strenuous activity) had hidden, and riding a snowbike is that—but hugely amplified.

And in that way, that most important and crucial, powerfully moving way, it’s exactly like riding a dirt bike. And that’s why I love it.

I don’t know if snowbiking will ever be a big thing, and I don’t necessarily know if it needs to be or if I think you need to go buy one. But I do think that, if you’re like me and love to try new things and love to explore this wonderful world we live in, you owe it to yourself to go somewhere you can rent one and try it out. I’ve gotten to do a lot of neat things in this job, and my two days in Wyoming’s backcountry are ones I’ll cherish for the rest of my life. I’m totally fine walking my snowbike across the road.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

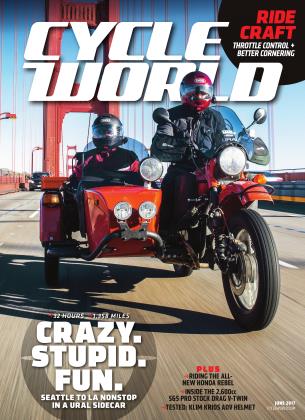

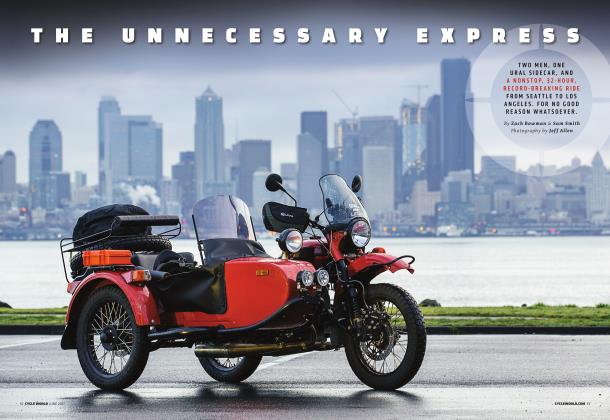

The Unnecessary Express

JUNE 2017 By Sam Smith, Zach Bowman -

Race Watch

Race WatchBig

JUNE 2017 By Kevin Cameron -

Ignition

IgnitionWhat Is the Four-Stroke Cycle?

JUNE 2017 By Kevin Cameron -

Service

ServiceService

JUNE 2017 By Ray Nierlich -

Up Front

Up FrontHarley Vs. Indian

JUNE 2017 By Mark Hoyer -

Ignition

IgnitionLost In the Supermarket

JUNE 2017 By Paul d’Orléans