WISHING

IGNITION

TDC

DAYTONA IS THE GREAT MEASURING STICK

KEVIN CAMERON

As Northeast winter has hung on with 15-degree days and subzero nights, I have yearned for Daytona as I knew it for so long. When I went to Daytona for the first time, in 1969, it was a moderately Big Deal, and the following year, with Honda, Triumph, and BSA in contention, it became a Bigger Deal. Then in 1972, quite by accident and through no one’s wisdom, it became The Greatest—the clash of the world’s fastest riders, on the world’s fastest machines, on the fastest track.

Because I was staying up nights changing crankshafts and cylinders,

I couldn’t know what was going on downtown, but Daytona was becoming every year’s big opportunity for trade shows, new model introductions, and every kind of corporate schmoozefest and high-zoot dinner meeting imaginable. AMA’s sudden success with 75OCC racing made European GP racing look small-time. Here in the US, nine factory teams contested the few AMA events of 1973, and powerful, innovative teams from Yamaha, Suzuki, and Kawasaki ran up front while hundreds of privateers on inexpensive 250 and 35OCC Yamaha production twins packed the grids. American racing was 100 percent driving motorcycle technology forward.

Name the great riders in those days and you knew you would see the whole list at Daytona. A top finish sold bikes and made careers.

Everyone with any motorcycle ambition had to be there, from the lowliest privateer with one novice bike to the big factory teams and the modern factories that fed America’s sudden 1970s hunger for motorcycles.

Daytona was The Great Measuring Stick. Can you pull the gear? Only one or two private TZ75OS could swing 18 teeth on the countershaft. Could your rider get through the chicane in second gear? It shot your adrenaline to see your bike rise up the list of practice times.

I wanted to stay at Daytona forever, staring into spark plugs, attempting to

predict when the sea breeze and the land breeze would add to zero.

Racing was only part of the action. Converging from all parts of the nation came rental vans and trailers stuffed with great big motorcycles on which their owners would soon pop and chuff up and down Daytona’s strip.

Remember the famous quote from the movie The Wild One:

“Hey, Johnny, what’re you rebelling against?” Mildred asks.

He answers, “Whaddya got?”

We weren’t there for baseball, football, or basketball. We were all on early release from our 9-to-5 sentences to run our motorcycles, use up our vacation days, burn through our savings. At Daytona we lived. We are glad we went, never mind less in the 401(K) and nothing in the college fund. We flourished in that hot sunlight.

Thirty years ago it was not yet an environmental crime to drive your motorhome onto the beach itself, find a parking space, and spread out your people in warm shade, close enough to hear the waves. National numbers under cover of darkness drove their rental cars out into the Atlantic and waded back, laughing, then were forever blacklisted by Hertz and “We Try Harder.” Daytona was a town of contrasts—sleeping, graceful old neighborhoods only a block away from the hotels, the bars, and strip clubs.

For the first many years I drove the 1,200 miles to this necessary festival.

I would start out in snow and cold, with the heater control on “hot.” As the miles rolled away, the outside air temperature moderated and the van grew warmer. We nudged the control toward the cool side. Somewhere south of Richmond, Virginia, with its tobacco headquarters and its classic railroad station, we’d stop for gas, and it would actually be warm. I’d hear the tree frogs calling. We had driven off the glacier, into springtime. Driving, driving, driving, and we’d come to a bridge, set about with palm trees, and on the far side, Florida.

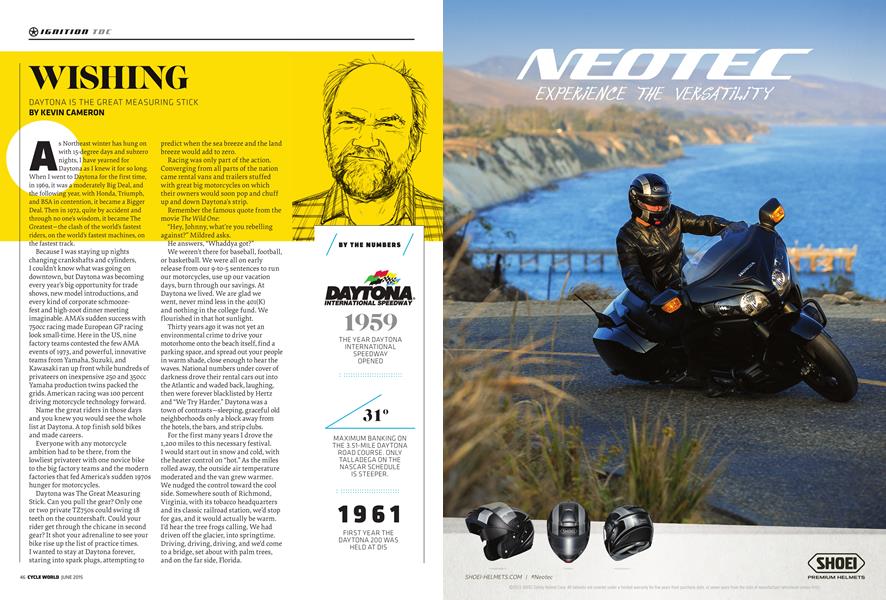

BY THE NUMBERS

1959 THE YEAR DAYTONA INTERNATIONAL SPEEDWAY OPENED

MAXIMUM BANKING ON THE 3.51-MILE DAYTONA ROAD GOURSE. ONLY TALLADEGA ON THE NASCAR SCHEDULE IS STEEPER.

1961 FIRSTYEARTHE DAYTONA 200 WAS HELD AT DIS

When I became a full-time magazine guy, it was more convenient to fly. In those years, they still rolled a stairway up to the door of the plane—no jetways for Daytona Beach regional airport. When the door opened, heat and humidity pressed in upon us wool-clad northerners. Find your rental car, start it, adjust the air conditioning, and roll along familiar streets to your hotel. No defroster, no ice scraper.

Today, International Speedway Avenue, which extends east from I-95 past the Speedway, then another 9 miles past the causeway to the oceanfront, is a major commuter route, all lanes filled, solid traffic at every rush hour. It was a lot less busy, a lot less built up 40 years ago. Today, many landmarks of that time are gone or carry new names. The exotic jai alai fronton is gone. But the sound of motorcycles is solid, around the clock. Half the Harleys ever made.

Mile-long ’Busas and ZX-14S with wheelie bars.

Daytona felt permanent then. It would always be this way. The box trucks of the MX teams would be lined up at the Indigo, mechanics building for Saturday. In the restaurants you’d see famous faces. Year after year, this was Daytona. Daytona was timeless.

I should have seen the change sooner—the replacement of hands-on race-team managers with the administrative Bobs and Bills of today. The replacement of actual teams by outside contract services. Honda US had its mysterious falling-out with HRC, began preparing its own bikes in-house, and was no longer pitted at the far end. GP racing gained a foothold at Laguna Seca and quietly took over the role of presenting the world’s fastest riders on the world’s fastest machines. American riders somehow ceased to leap from

AMA 750 or Superbike to 500 GP, as Kenny Roberts, Eddie Lawson, Freddie Spencer, Wayne Rainey, and Kevin Schwantz had done. Times had changed. No Big Deal lasts forever, and maybe we had been lucky this one lasted as long as it did. The Deal remained Big only so long as US motorcycle sales did the same.

The Isle of Man TT races once held the same absolute powerdrawing the major foreign and domestic teams, filling hotels and restaurants, turning speed into sales and skill into fame and fortune. After 1976, the TT ceased to be part of the GP season. It didn’t matter—the TT has unique appeal, so racing continues there to this day. Daytona is no longer AMA racing’s season opener, but like the TT, it too will surely continue. Daytona’s high bankings can no more be ignored than can the TT’s century of racing on public roads. C1U

NAME THE GREAT RIDERS IN THOSE DAYS AND YOU KNEW YOU WOULD SEE THE WHOLE LISTAT DAYTONA.

A TOP FINISH SOLD BIKES AND MADE CAREERS.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

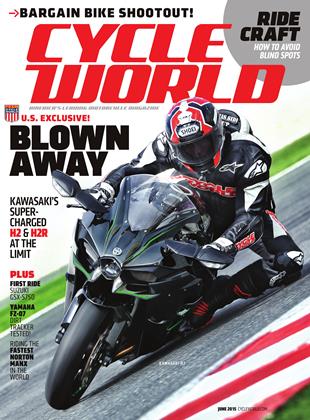

More From This Issue

-

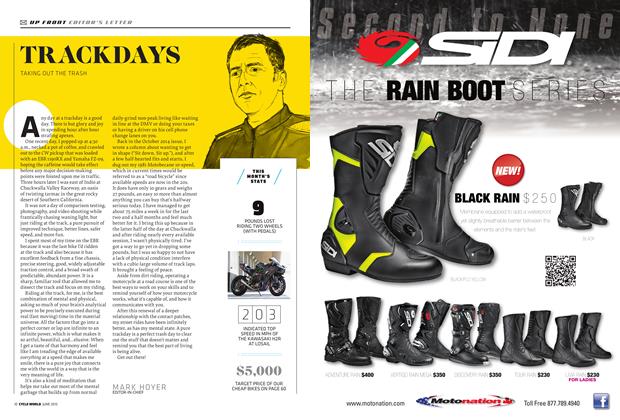

Up Front

Up FrontTrackdays

June 2015 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

June 2015 -

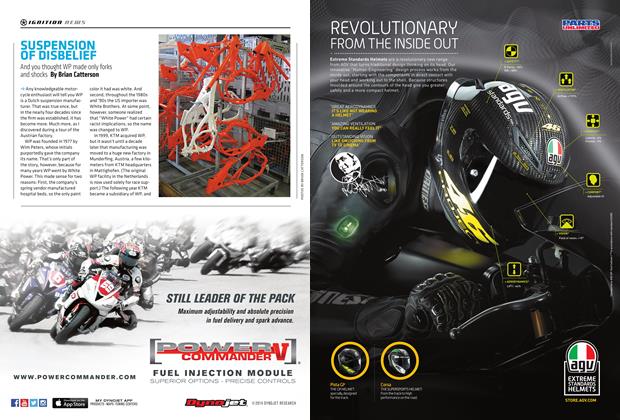

Ignition

IgnitionSuspension of Disbelief

June 2015 By Brian Catterson -

Ignition

IgnitionCw 25 Years Ago

June 2015 By Andrew Bornhop -

Ignition

IgnitionTop Priority: Street Riding Avoid the Blind Spot

June 2015 By Nick Lenatsch -

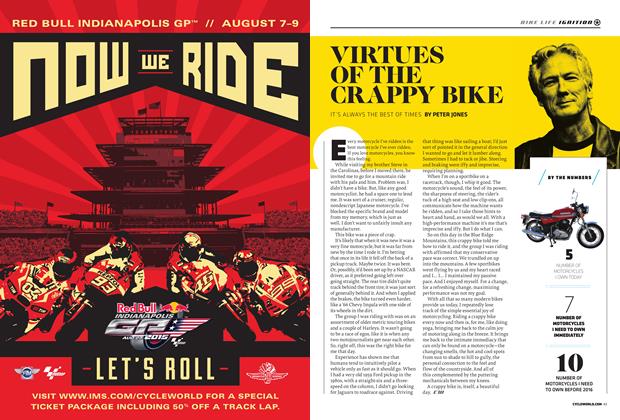

Ignition

IgnitionVirtues of the Crappy Bike

June 2015 By Peter Jones