TDC

Lost Opportunities

KEVIN CAMERON

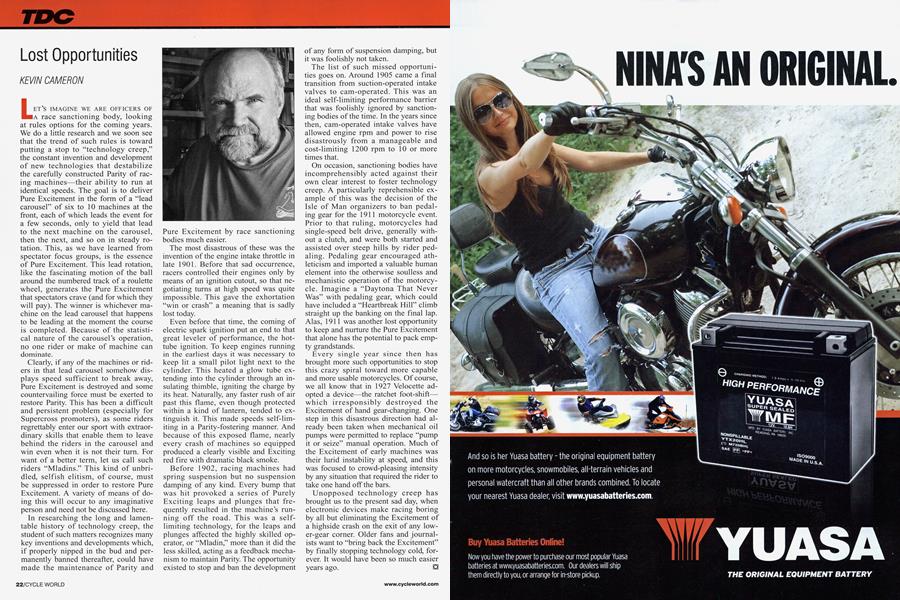

LET’S IMAGINE WE ARE OFFICERS OF A race sanctioning body, looking at rules options for the coming years. We do a little research and we soon see that the trend of such rules is toward putting a stop to “technology creep,” the constant invention and development of new technologies that destabilize the carefully constructed Parity of racing machines—their ability to run at identical speeds. The goal is to deliver Pure Excitement in the form of a “lead carousel” of six to 10 machines at the front, each of which leads the event for a few seconds, only to yield that lead to the next machine on the carousel, then the next, and so on in steady rotation. This, as we have learned from spectator focus groups, is the essence of Pure Excitement. This lead rotation, like the fascinating motion of the ball around the numbered track of a roulette wheel, generates the Pure Excitement that spectators crave (and for which they will pay). The winner is whichever machine on the lead carousel that happens to be leading at the moment the course is completed. Because of the statistical nature of the carousel’s operation, no one rider or make of machine can dominate.

Clearly, if any of the machines or riders in that lead carousel somehow displays speed sufficient to break away, Pure Excitement is destroyed and some countervailing force must be exerted to restore Parity. This has been a difficult and persistent problem (especially for Supercross promoters), as some riders regrettably enter our sport with extraordinary skills that enable them to leave behind the riders in the carousel and win even when it is not their turn. For want of a better term, let us call such riders “Mladins.” This kind of unbridled, selfish elitism, of course, must be suppressed in order to restore Pure Excitement. A variety of means of doing this will occur to any imaginative person and need not be discussed here.

In researching the long and lamentable history of technology creep, the student of such matters recognizes many key inventions and developments which, if properly nipped in the bud and permanently banned thereafter, could have made the maintenance of Parity and Pure Excitement by race sanctioning bodies much easier.

The most disastrous of these was the invention of the engine intake throttle in late 1901. Before that sad occurrence, racers controlled their engines only by means of an ignition cutout, so that negotiating turns at high speed was quite impossible. This gave the exhortation “win or crash” a meaning that is sadly lost today.

Even before that time, the coming of electric spark ignition put an end to that great leveler of performance, the hottube ignition. To keep engines running in the earliest days it was necessary to keep lit a small pilot light next to the cylinder. This heated a glow tube extending into the cylinder through an insulating thimble, igniting the charge by its heat. Naturally, any faster rush of air past this flame, even though protected within a kind of lantern, tended to extinguish it. This made speeds self-limiting in a Parity-fostering manner. And because of this exposed flame, nearly every crash of machines so equipped produced a clearly visible and Exciting red fire with dramatic black smoke.

Before 1902, racing machines had spring suspension but no suspension damping of any kind. Every bump that was hit provoked a series of Purely Exciting leaps and plunges that frequently resulted in the machine’s running off the road. This was a selflimiting technology, for the leaps and plunges affected the highly skilled operator, or “Mladin,” more than it did the less skilled, acting as a feedback mechanism to maintain Parity. The opportunity existed to stop and ban the development of any form of suspension damping, but it was foolishly not taken.

The list of such missed opportunities goes on. Around 1905 came a final transition from suction-operated intake valves to cam-operated. This was an ideal self-limiting performance barrier that was foolishly ignored by sanctioning bodies of the time. In the years since then, cam-operated intake valves have allowed engine rpm and power to rise disastrously from a manageable and cost-limiting 1200 rpm to 10 or more times that.

On occasion, sanctioning bodies have incomprehensibly acted against their own clear interest to foster technology creep. A particularly reprehensible example of this was the decision of the Isle of Man organizers to ban pedaling gear for the 1911 motorcycle event. Prior to that ruling, motorcycles had single-speed belt drive, generally without a clutch, and were both started and assisted over steep hills by rider pedaling. Pedaling gear encouraged athleticism and imported a valuable human element into the otherwise soulless and mechanistic operation of the motorcycle. Imagine a “Daytona That Never Was” with pedaling gear, which could have included a “Heartbreak Hill” climb straight up the banking on the final lap. Alas, 1911 was another lost opportunity to keep and nurture the Pure Excitement that alone has the potential to pack empty grandstands.

Every single year since then has brought more such opportunities to stop this crazy spiral toward more capable and more usable motorcycles. Of course, we all know that in 1927 Velocette adopted a device—the ratchet foot-shift— which irresponsibly destroyed the Excitement of hand gear-changing. One step in this disastrous direction had already been taken when mechanical oil pumps were permitted to replace “pump it or seize” manual operation. Much of the Excitement of early machines was their lurid instability at speed, and this was focused to crowd-pleasing intensity by any situation that required the rider to take one hand off the bars.

Unopposed technology creep has brought us to the present sad day, when electronic devices make racing boring by all but eliminating the Excitement of a highside crash on the exit of any lower-gear corner. Older fans and journalists want to “bring back the Excitement” by finally stopping technology cold, forever. It would have been so much easier years ago. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue