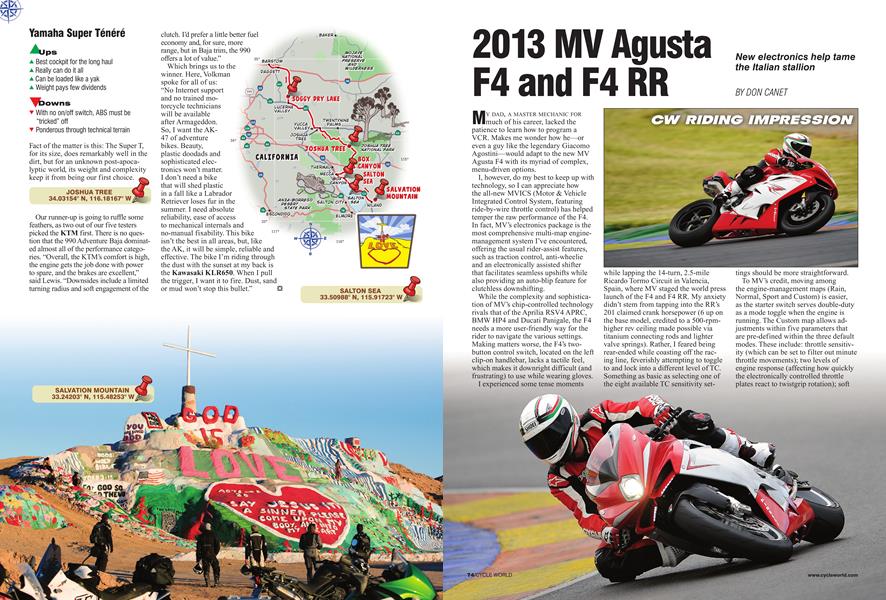

2013 MV Agusta F4 and F4 RR

CW RIDING IMPRESSION

New electronics help tame the Italian stallion

DON CANET

MY DAD, A MASTER MECHANIC FOR much of his career, lacked the patience to learn how to program a VCR. Makes me wonder how he—or even a guy like the legendary Giacomo Agostini—would adapt to the new MV Agusta F4 with its myriad of complex, menu-driven options.

I, however, do my best to keep up with technology, so I can appreciate how the all-new MVICS (Motor & Vehicle Integrated Control System, featuring ride-by-wire throttle control) has helped temper the raw performance of the F4.

In fact, MV’s electronics package is the most comprehensive multi-map enginemanagement system I’ve encountered, offering the usual rider-assist features, such as traction control, anti-wheelie and an electronically assisted shifter that facilitates seamless upshifts while also providing an auto-blip feature for clutchless downshifting.

While the complexity and sophistication of MV’s chip-controlled technology rivals that of the Aprilia RSV4 APRC, BMW HP4 and Ducati Panigale, the F4 needs a more user-friendly way for the rider to navigate the various settings. Making matters worse, the F4’s twobutton control switch, located on the left clip-on handlebar, lacks a tactile feel, which makes it downright difficult (and frustrating) to use while wearing gloves. I experienced some tense moments

while lapping the 14-turn, 2.5-mile Ricardo Tormo Circuit in Valencia, Spain, where MV staged the world press launch of the F4 and F4 RR. My anxiety didn’t stem from tapping into the RR’s 201 claimed crank horsepower (6 up on the base model, credited to a 500-rpmhigher rev ceiling made possible via titanium connecting rods and lighter valve springs). Rather, I feared being rear-ended while coasting off the racing line, feverishly attempting to toggle to and lock into a different level of TC. Something as basic as selecting one of the eight available TC sensitivity settings should be more straightforward.

To MV’s credit, moving among the engine-management maps (Rain, Normal, Sport and Custom) is easier, as the starter switch serves double-duty as a mode toggle when the engine is running. The Custom map allows adjustments within five parameters that are pre-defined within the three default modes. These include: throttle sensitivity (which can be set to filter out minute throttle movements); two levels of engine response (affecting how quickly the electronically controlled throttle plates react to twistgrip rotation); soft or hard rev limiters; two engine-braking settings (that determine how much the throttle plates remain cracked open during deceleration); and lastly, torque output (which emulates Rain mode’s reduced peak output via limiting maximum throttle-plate opening when the twistgrip is pinned).

Four 20-minute riding sessions weren’t nearly enough to try all of the possibilities, but my two stints on the RR did introduce me to its deeper electronic wizardry, which includes electronically adjustable Öhlins suspension in place of the Marzocchi fork and Sachs shock of the base model. Switching the RR’s engine-management maps also alters the pre-configured values for compression and rebound damping. While not an active system like that of the BMW HP4, the digital upgrades offer an electronic screwdriver, if you will. Making damping changes while stopped on pit lane proved tedious because the switch on the left bar only allowed the numerical damping value to be bumped in an upward direction.

A lot of button presses are required to go from a setting of 10 to 9, for example, requiring you to loop through the full 20-“click” range just to get to 9.

The RR also employs an electronically adjustable steering damper with two modes. Manual lets you assign a degree of damping within yet another dash menu, while Auto dynamically adjusts firmness to suit the bike’s speed or rate of acceleration—a good street option. The conventional clicker knob of the base F4’s CRC damper proved much easier to adjust when finding a setting to quell the bar movement both models exhibited while driving hard off corners and skimming the front wheel over rumble strips.

Beautifully crafted forged wheels (the lightest possible using aluminum, says MV) give the RR an agility advantage over its cast-wheeled sibling. Both models,

though, require little effort to bend into turns and track solidly through apexes.

I also marveled at the grip of the stock Pirelli Supercorsa SP radiais, as well as the F4’s seemingly limitless cornering clearance.

My best laps came with the throttle sensitivity and response settings set to Normal, in conjunction with a leastintrusive TC setting of 1. This took the edge off, freeing up focus for hitting my marks and exploiting the superb chassis. The TC strategy, which retards ignition advance and then manipulates the throttle, produces a smooth, stutter-free reduction in power output.

I found the auto-blip downshifts greatly ease rider workload when charging deep into corners, allowing my full attention to be placed on braking. It’s never been easier to maintain constant lever pressure and front-end load while changing down through the gearbox, making good use of the powerful Brembo Monobloc M50 calipers on the RR or the F4’s equally impressive (if not as exclusive) Monobloc M4 binders.

The downhill approach to the circuit’s final corner provided a testament to the system. While downshifting with the bike banked over, I never felt the rear step out of line as I pressed the shift lever and simply left the twistgrip and clutch alone.

All told, MV Agusta has made great strides in harnessing the power and performance that F4s have always possessed. While not exactly your father’s MV the F4, thanks to the magic of MVICS, is more refined and accessible than ever. Just imagine what Ago could do on such a machine. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontBeing Prepared

APRIL 2013 By Mark Hoyer -

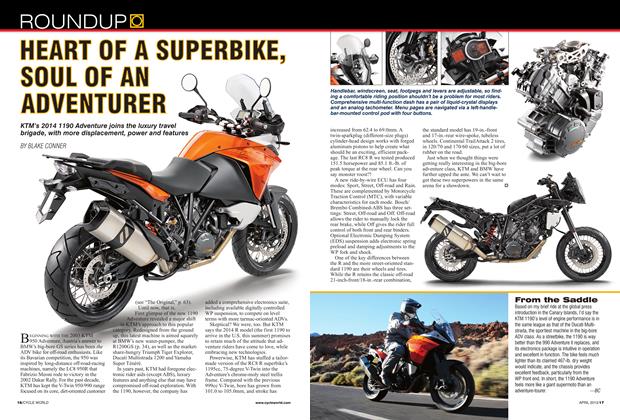

Roundup

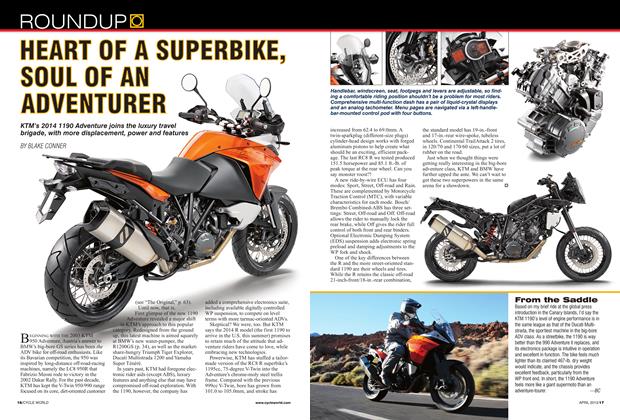

RoundupHeart of A Superbike, Soul of An Adventurer

APRIL 2013 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupFrom the Saddle

APRIL 2013 By BC -

Roundup

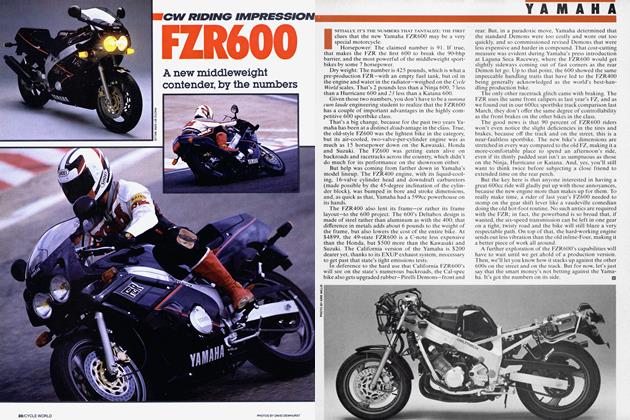

Roundup25 Years Ago April 1988

APRIL 2013 By Don Canet -

Roundup

RoundupWill Elastomers Change Helmet Design?

APRIL 2013 By Andrew Bornhop -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

APRIL 2013