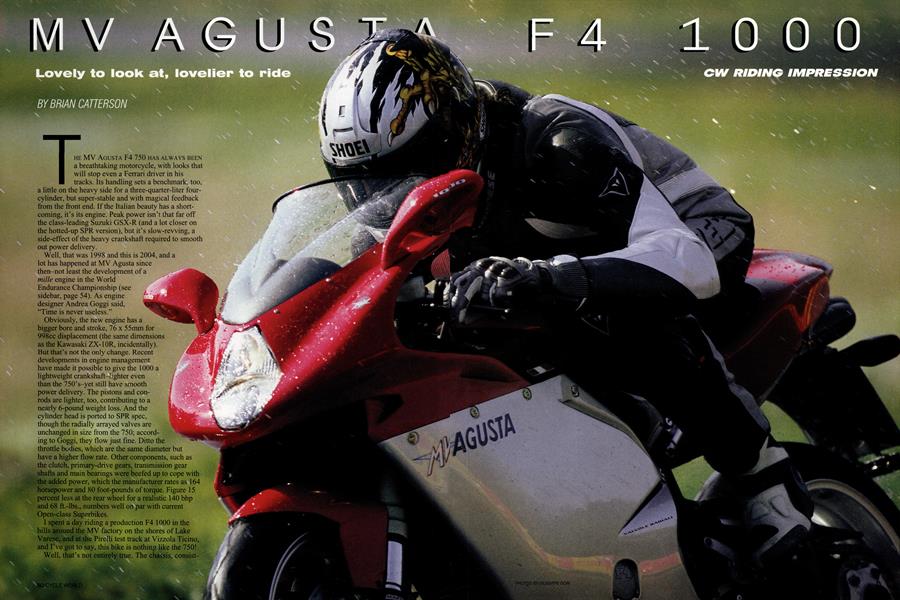

MV AGUSTA F4 1000

Lovely to look at, lovelier to ride

BRIAN CATTERSON

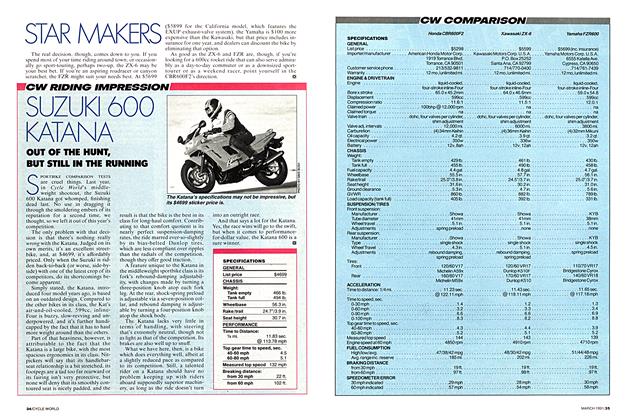

THE MV AGUSTA F4 750 HAS ALWAYS BEEN a breathtaking motorcycle, with looks that will stop even a Ferrari driver in his tracks. Its handling sets a benchmark, too, a little on the heavy side for a three-quarter-liter fourcylinder, but super-stable and with magical feedback from the front end. If the Italian beauty has a shortcoming, it’s its engine. Peak power isn’t that far off the class-leading Suzuki GSX-R (and a lot closer on the hotted-up SPR version), but it’s slow-revving, a side-effect of the heavy crankshaft required to smooth out power delivery.

Well, that was 1998 and this is 2004, and a lot has happened at MV Agusta since then-not least the development of a mille engine in the World Endurance Championship (see sidebar, page 54). As engine designer Andrea Goggi said, “Time is never useless.”

Obviously, the new engine has a bigger bore and stroke, 76 × 55mm for 998cc displacement (the same dimensions as the Kawasaki ZX-10R, incidentally). But that’s not the only change. Recent developments in engine management have made it possible to give the 1000 a lightweight crankshaft-lighter even than the 750’s-yet still have smooth power delivery. The pistons and conrods are lighter, too, contributing to a nearly 6-pound weight loss. And the cylinder head is ported to SPR spec, though the radially arrayed valves are unchanged in size from the 750; according to Goggi, they flow just fine. Ditto the throttle bodies, which are the same diameter but have a higher flow rate. Other components, such as the clutch, primary-drive gears, transmission gear shafts and main bearings were beefed up to cope with the added power, which the manufacturer rates as 164 horsepower and 80 foot-pounds of torque. Figure 15 percent less at the rear wheel for a realistic 140 bhp and 68 ft.-lbs., numbers well on par with current Open-class Superbikes.

I spent a day riding a production F4 1000 in the hills around the MV factory on the shores of Lake Varese, and at the Pirelli test track at Vizzola Ticino, and I’ve got to say, this bike is nothing like the 750! Well, that’s not entirely true. The chassis, consisting of a chromoly-steel spaceframe with single-sided aluminum swingarm, is unchanged save for a taller 70-series front tire that increases rake by half a degree, to 24.5. The seating position has also been subtly altered, with reangled clip-ons and adjustable footpegs that, together with the taller “double-bubble” windscreen, make droning on the street a bit more bearable. And the adjustable swingarm pivot previously offered only on the high-dollar F4 Oro is now standard. As for Massimo Tamburini’s styling, that looks as fresh as ever, the only change from the 750 small “1000” logos on the tail and mirrors-the latter, incidentally, as useless as ever.

CW RIDING IMPRESSION

Push the starter button, twist the throttle and the tachometer needle zings up to the engine's 12,750-rpm rev-limit notice ably quicker than on the 750. That tach, by the way, now has a white face rather than yellow. In spite of the engine not hay ing a counterbalancer, vibration is surprisingly low.

Click the transmission into first, let out the (quite stiff) clutch and you’ll note that the 1000 is geared tall, requiring a fair amount of clutch slippage to get off the line. But once under way, the engine impresses you with its potency, with strong torque flowing as low as 3000 rpm. The MV doesn’t snap up the front wheel like a ZX-10, and it doesn’t have the top-end rush of a Yamaha YZF-R1, but it’s a nice compromise between the two.

"For sure, it is not a peaky engine," allowed Goggi. "Torque, I think, is the reason people buy l000s."

Not that the MV doesn’t make impressive top-end power, too. Hold the throttle open in the upper reaches of the rev range and the 1000 blurs the scenery in a way the 750 never could. It’s seriously fast! Certainly too fast to push hard on the street, which is why MV arranged the use of Pirelli’s test track. Between sessions watching Italian crazies broadslide big-rigs in the wet, I was able to wring out the 1000 (after they turned off the track sprinklers, thank you very much), and came away impressed. Its chassis feels perfectly balanced, like a Ducati 916/996/998 only with a bit more weight on the front end-crankshaft center closer to the tire contact patch, perhaps? Handling of the 422-pound machine is generally light, thanks in part to the lightweight engine internals, and while steering remains slightly heavy, it’s dead neutral, as I discovered while doing laps of the skid pad for photos. (I also discovered how easy it was to melt my size-11 boot heel on the rear tire, courtesy of the single-sided swingarm!) With the tires nearing their traction limits, adjusting chassis balance is a simple matter of turning the throttle one way or the other, and that “throttle connection” is apparent at comer exits, too-few production sportbikes are as easy to steer with the rear. Helping matters is the 1000’s unflappable stability (aided by the standard Öhlins steering damper, no doubt), even at an indicated 250 kph (155 mph) on the test track’s relatively short straightaway. Top speed is said to nudge 300 kph (186 mph). Where the 1000 most impresses, though, is at comer entrances, where the innovative EBS (Electronic Braking System) does an exceptional job of preventing engine braking from inducing rear-wheel chatter. Similar to the system

used on some MotoGP bikes, EBS works with the ECU to hold open the valves on the #2 cylinder on trailing throttle, and lets air flow through via a solenoid valve in the intake tract. Voila, instant two-stroke! But no matter how it works, it’s magic, allowing late braking and impossibly quick downshifts while giving the rider the option of “backing it in” on the brakes with no fear of hysterics. Supermoto bikes should work this well! The fact that the Nissin brakes (sixpiston in front) require very light pressure, and that the Marzocchi 50mm fork and Sachs shock (the latter with highand low-speed compression-damping and hydraulic spring-preload adjustments) have that just-right balance of springing and damping obviously helps. Too bad MV chose not to participate in Master Bike 2004; the F4 would have been an interesting addition. Whatever their reason, after a two-year period wherein a stalled deal with the Piaggio Group forced production to slow to a trickle, the company is on the cusp of another renaissance. A recent influx of capital from Italy’s Banca Intensa got the assembly lines moving again, and a big-money deal with Malaysian auto-maker Proton is said to be pending. That’s good news for those worried about manufacturer support. But if MV owners have had occasion to wonder about parts and service, they’ve never had to make excuses for their motorcycles, and the F4 1000 hammers that point home. It may not rival Japanese bikes in terms of bang-for-the-buck, but it offers comparable performance plus other qualities such as exclusivity, pride of ownership and high resale value. It’s a piece of art you can ride. Really, really fast. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontDer Meister Aller Klassen

September 2004 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsAdventures In Fuel Mileage

September 2004 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThe Combustion Compromise

September 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2004 -

Roundup

RoundupPower To the People!

September 2004 -

Roundup

RoundupEtc.

September 2004