Waiting for Change

RACE WATCH

Is MotoGP inching toward something different?

KEVIN CAMERON

AMID THE CONFUSION OF PURPOSE THAT IS TODAY'S MOTOGP, HONDA'S Casey Stoner won his bet on a soft tire this past July at Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca. Current points-leader Jorge Lorenzo, who had put his factory Yamaha at the top of practice and qualifying, pulled away by intense concentration. But the Spaniard's lead peaked on Lap 14 at 1.5 seconds and by Lap 20, Stoner, deploying the soft tire he had conserved so carefully, was inches behind. A high-grip execution of Turn 11 launched Stoner on a pass that was completed on the inside into the Turn 2 "bowl." The finish was Stoner, Lorenzo, Dani Pedrosa, Andrea Dovizioso, Cal Crutchlow—two Hondas, three Yamahas. Before the race, top riders felt the hard tire was too hard and the soft tire too soft. Stoner accepted the ancient wisdom that you use the softest tire you can get to the finish.

Encouragement for those who hope this year's CRT bikes with their productionbased engines may one day amount to more than a novelty came from Aleix Espargaro's ninth place on an Aprilia ART. Nicky Hayden put his Ducati in sixth, while teammate Valentino Rossi crashed out of eighth—his first DNF of this season—two laps from the end.

Stoner won despite this year's Honda chronic problems of front and rear chatter, braking instability and gradual loss of tire properties. "When there's chatter this aggressive on these bumps—definitely a little bit worse than last year—there's no feedback, no feeling," said the Australian. "It's very hard to push through that and make up time without crashing."

Rear chatter was largely overcome at the British GP at Silverstone but was asymmetrical and worse on the right. Front chatter has not yet been quelled and is present on both sides. Stoner went on to comment that asymmetrical chatter implies the bike's structural stiffness is also asymmetrical. Very strange!

What else is strange is that the current Honda was chatter-free with the 2011 tires on which it was developed. But on the softer-construction, faster-warmup tires Bridgestone created for this season, Stoner said, "We went from a bike that was working really well—we were going to be competitive—and [those new] tires completely destroyed it."

Honda is powerful. People know Honda is the real voice of the Motor Sports Manufacturers'Association (MSMA), which is responsible for setting MotoGP displacement at 990cc then dropping it to 800 for 2007. Countless Bridgestone tires equip new Honda products. An outfit with such power could murmur a few words to the right executive golf partner and, presto, last year's tires stay on the list. Because that didn't happen, people wonder what kind of executive murmuring passes between seriesrights-holder Dorna and Bridgestone.

I asked Stoner about today's cornerspeed riding style. He explained that, despite a rider's own style, the evolution of the Bridgestone tires has forced riders to adopt high comer speed. Why is this? The bulging, round-profile MotoGP Bridgestones deliver the same grip, spread out over the same footprint, from edge to center. This means that the classic style of lifting up the bike early in a turn to lay down a bigger footprint on which to accelerate hard just doesn't work any more.

"Dani and I are up front, and Bridgestone didn't develop the tires for us," said Stoner. "Mid-pack guys having a say in what direction the tires are supposed to go, that's our main issue."

As a result, everyone rides the cornerspeed style, like it or not. In a spec-tire series, riders and machines must adapt to the tires, not the other way around.

I asked Pedrosa about Honda's attempts to adapt with new chassis this year. "We try several chassis now," he replied. "This is the third one. Chatter didn't change much. It is hard because grip is so important. All the things that go for less chatter also go for less grip."

Colin Edwards is now riding a BMWpowered Suter CRT for Forward Racing after being dropped from the satellite Tech 3 Yamaha team. At the season opener in Qatar, Edwards had the worst chatter he'd ever experienced until they moved weight off the front by tipping the bike rearward.

"We're looking for the ballpark," he said. "We need a test rider to find the ballpark [every prototype and satellite bike is well set up from the factory], so my job can be the fine-tuning."

This is the central problem of CRT: Snapping together a "LEGO bike" from this engine, that chassis, those wheels and suspension leaves the user to "find the ballpark" to transform a parts list into a racing motorcycle. Factories have departments for this, so it's a tall order for a private team to look for the ballpark and race at the same time.

"All the CRT guys fly around the world to what, maybe finish 12th?" asked Edwards. "What sponsor is going to pay for that?"

Did the changes kill the chatter? "It doesn't chatter now, but we might have it back this afternoon," he laughed. "But the thing doesn't turn." That is just what Stoner and Pedrosa said: What kills chatter also kills grip. In the race, this experienced two-time World Superbike champion would run 17th, move up to 13th and finish one lap down to Stoner.

Honda team boss Shuhei Nakamoto weighed in on chatter. "Usually, chattering is 25 Hz, but [our] data is showing 20 Hz. Riders are saying, 'Chattering, chattering,' but this is not chatter from an engineering point of view. We have no experience [with 20 Hz chatter]. We are striving to find a solution."

I asked Stoner about CRT bikes,

which some consider "the future of MotoGP." He pointed to their slowness—3 to 5 seconds per lap behind the prototypes—and generally modest level of riders. "Sad to say, a lot of the [CRT] riders don't belong in MotoGP. They got there because somebody had money."

Pedrosa, on the same subject, was characteristically cautious. "We've seen many changes, and maybe we believe these changes are forever. It may be that in this crisis, this is the best solution. We must be patient."

Pedrosa is riding at his highest level ever this year—always in the top three, not crashing. What has changed?

"I change some things," he said, "improve some areas. Not everything is related to racing—more the way to approach the racing. I am more relaxed now, not so upset, and the body feels better [he has had many injuries in the past], I am not so 'mental.' Braking, gearchanging are more automatic. I feel these things and do not lose the focus."

I heard wheelspin from the Hondas up the hill past start/finish. Stoner, Pedrosa and LCR Honda rider Stefan Bradl all acknowledged this tire spin. Stoner said it was an underlying problem, contributing to more-rapid tire fatigue all this year.

Pedrosa added, "This year, it seems Yamaha is so strong in the straight, in acceleration. But we were wondering is the engine so strong? Or is it because we lose the traction out of the corners? We are trying to reduce this spinning."

It was also very interesting to hear current views on electronics. Like Rossi three years ago, they are saying that if low-throttle electronics were not available, top riders would stand out more because of their throttle-control skills. If tires were more like the Michelins of the late 500cc two-stroke era with less edge grip, the dangers of early acceleration would keep back second-level riders.

How can the Hondas spin if traction control is so effective? Stoner commented, "It's much slower to just sit on the electronics, maybe safer."

"Sitting on the electronics" means putting traction and wheelie control on high settings so they are operating most of the time. Because engines are now smoothed by the technique called "virtual powerband," top riders prefer to use the electronics sparingly to preserve their ability to spin the tire when needed.

Back in 2007, everyone thought Stoner was so fast on the 800cc Ducati because of mysterious Formula One-inspired electronics, but, in fact, the secret control system was himself, forcing the understeering and rear-heavy machine around corners by spinning the back tire. Yamaha fought back with electronics. It was like the Russians building the MiG-25 to counter an airplane—the U.S. B-70 supersonic bomber—that was never produced.

A Laguna subtext was the effort of the American Attack Performance team to qualify its CRT entry designed by team owner Richard Stanboli and ridden by Steve Rapp. As Rapp and the team moved toward the magic 107-percentof-session qualifying time, Lorenzo also lapped quicker, lowering pole. In the end, Rapp missed by 0.4 second.

As we know, Rossi has now announced a two-year contract to return to Yamaha next year after two seasons on a Ducati that has been generally a second off the pace. His teammate, Hayden, has re-signed with Ducati for another year. When I spoke with Rossi's crew chief, Jeremy Burgess,

he posed the question, "What do you do when you have a problem? You do something. Honda would build 10 chassis and establish a direction."

Despite the long series of small changes tested, Ducati has again and again postponed a "big change" that has yet to appear. While the approach of Honda and Yamaha to such things is clearly empirical, Ducati seems wedded to the theoretical, as if handling issues can best be solved on computer screens. Good luck to them.

After hearing the quaver of the Hondas, my next interview was with Bridgestone 's Hiroshi Yantada, who is said to be the man who first proposed that company enter MotoGP. When I mentioned the spinning, he said, "Spinning? You hear? Really?

Here at Laguna?"

I had to think about this. During first 500cc practice at the 1990 U.S. GP, 1 had heard the new electronic torque controls convert off-corner acceleration from 1989's slip-and-grip near-highsides into smooth, controlled drives. Yet FIM officials, sealed away from the action in their offices, remained in crisis mode, threatening intake restrictors. Must top officials always be the last to know when times change? About this year's softer-construction, faster-warmup tires, Yamada said, "We discuss with riders, Dorna and 1RTA

[International Road Racing Teams Association] safety commission. Almost everybody prefers this construction— just one or two riders don't like. We want everybody to be happy, but this is not possible."

I asked both Yamada and Nakamoto if they had made slow-motion videos of chatter but could not get a yes or no answer! Is chatter research so secret that nobody is doing any?

Bradl, who finished seventh, described his transition from Moto2 to MotoGP by saying, "You cannot go so much on corner speed. You have to be prepared for the exit all the time, to use the power as much as you can. If you are always leaning, you cannot bring the power on the ground."

As more change is rumored by Dorna—a 15,000or even-lower-rpm redline, spec ECU and further weight increases—it seems that the goal is to "undevelop" the prototypes to make the CRTs competitive. That will be seriously slow! Or is the real goal to force the manufacturers to build lower-cost "production racers" as Honda has announced for 2014?

Stoner summed up the current state of the series by saying, "Changing rules splits the manufacturers apart. If the rules stayed the same, like they did for 50 years [1949-2001], Kawasaki and Suzuki would still be with us; they'd have enough time to develop a competitive bike. They keep changing the rules because that's what they do in Formula One. It's a very touchy subject in Dorna for a certain person if you even mention Formula One in his presence."

Only one thing seems certain: change. In some direction. We await the next batch of fresh rules.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

NOVEMBER 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupNo Quarter Given

NOVEMBER 2012 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago November 1987

NOVEMBER 2012 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupWill the Motorcycle of the Future Come From Pasadena?

NOVEMBER 2012 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

Roundup2013 Harley-Davidsons

NOVEMBER 2012 By Paul Dean -

Roundup

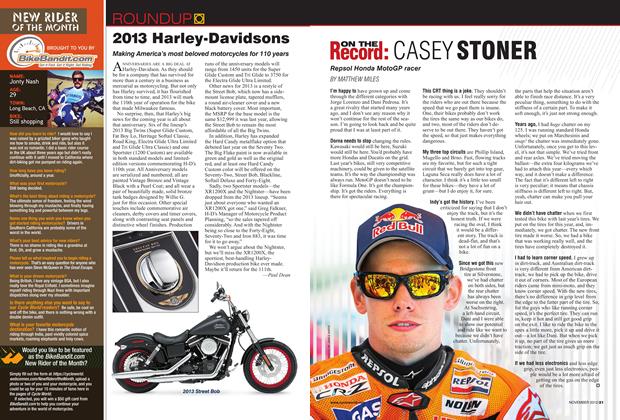

RoundupOn the Record:

NOVEMBER 2012 By Matthew Miles