What Do Bicycles, Metalsmithing, Furniture Design, Ceremonial Swords And Suzuki Gt750s Have In Common?

July 1 2011 John BurnsWhat Do Bicycles, Metalsmithing, Furniture Design, Ceremonial Swords And Suzuki Gt750s Have In Common? JOHN BURNS July 1 2011

WHAT DO BICYCLES, METALSMITHING, FURNITURE DESIGN, CEREMONIAL SWORDS AND SUZUKI GT750S HAVE IN COMMON?

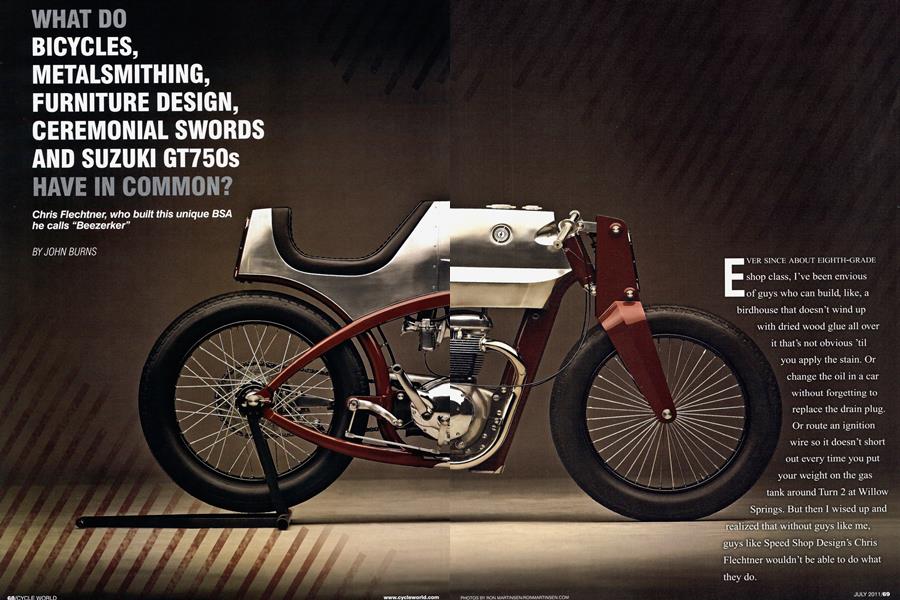

Chris Flechtner, who built this unique BSA he calls “Beezerker”

JOHN BURNS

EVER SINCE ABOUT EIGHTH-GRADE shop class, I've been envious of guys who can build, like, a birdhouse that doesn't wind up with dried wood glue all over it that's not obvious 'til you apply the stain. Or change the oil in a car without forgetting to replace the drain plug. Or route an ignition wire so it doesn't short out every time you put your weight on the gas tank around Turn 2 at Willow Springs. But then I wised up and realized that without guys like me, guys like Speed Shop Design's Chris Flechtner wouldn't be able to do what they do.

"What we're looking at is the kind of patient perfectionism that borders masochism."

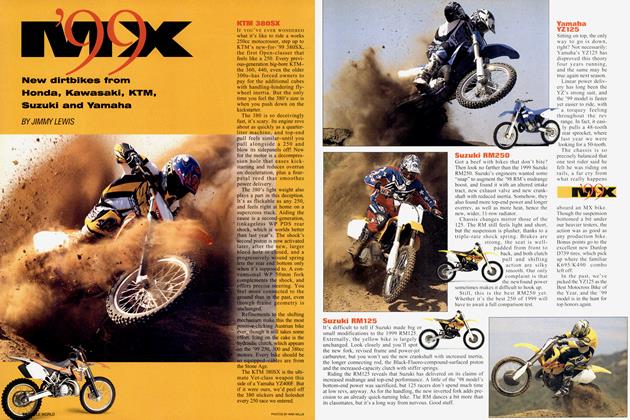

If some friend of a friend hadn’t trashed an old BSA and abandoned it for 10 years in a moldy shed, for instance, it would’ve been too nice a machine to turn into the thing that would be known as “Beezerker.” “It was the typical deal,” begins Flechtner. “Ten years seems to be the standard length of time it takes people to realize they’re never going to get around to it. It was choppified, with struts in the back. It had twin coils strapped to the downtubes and holes drilled in the engine cover to get to the electricals. It was really in sad shape. It made it easy to decide to just keep the engine and get rid of the rest—the frame had been cut up and poorly welded, the sheet metal was all dented...”

And so the young Seattleite set to work, and not the kind that involves buying parts on the www. The Beezerker began with a downtube that started out as a 2-inchround, !/8-inch-wall-thickness steel tube too strong to bend in Flechtner’s shop. So, he had the local boiler-works bend the tubing to fit templates he made, then cut the tube in half lengthwise and welded in flat bars to create his own “oval tubing,” a theme he continued throughout his BSA hardtail. Including the part of the frame into which the exhaust pipes flow, which then turns upward ahead of the rear wheel and exits out the rear grille—a subfendertype thing so cleanly executed you don’t notice there’s no exhaust until you notice (days later, in my case) there’s no exhaust.

The fact that he’d never worked with aluminum sheet before didn’t dissuade Flechtner from diving right in, either, bending and welding Beezerker’s bodywork from 3003 aluminum sheet. “I’d done a lot of heavier aluminum welding, but this time was tough,” he admits. “I made things difficult for myself trying to keep everything so smooth, and the crisp comers took a lot of patience. It didn’t go quickly.”

What we’re looking at is the kind of patient perfectionism that borders masochism. Apart from the 20-inch clincher rims and the Harley Wide Glide front hub that serves as Beezerker’s rear hub, Flechtner fabricated or modified just about everything on the bike, including the stainless steel grips. Why not? Just take a mold of the rubber grips, remove the rubber, make a wax casting of that, then have your buddy at the local foundry pour in 316 stainless steel.

Obviously, these skills don’t just show up overnight. As a kid, Flechtner worked in a bicycle shop in his native Fitchburg, Massachusetts, where he was exposed to the owner’s collection of vintage Iver Johnson bicycles, after having been exposed to his dad’s Suzuki GT750 “Water Buffalo” and a series of Big Wheels and bicycles “customized” to match it. “My dad always rode motorcycles to work and left my mom the car,” says Flechtner. “Before I was bom, he quit scrambling.

He had a bunch of Bultacos but had a bad crash while my mom was on the sidelines pregnant with me and decided he’d rather see his kid born than race. But we had tons of trophies and things. When he’d talk about it, he’d get so excited. It was back during the era when the Europeans were coming over to race for the first time. He met Mr. Bulto himself, talked about motorcycle design with him.”

In college in Boston, Flechtner studied metalsmithing and wound up with a degree in Fine Art (and later a master’s in furniture design). In college, though, his bicycle fetish continued, and he built full suspension bikes for fun. “Girder forks are a simple concept,” he says, and so the Beezerker has a very pretty hand-built one In fact, compared to custom furniture design, which is what Flechtner does during the day, and helping a master sensei tune up priceless katanas as a sideline (not the Suzuki kind), throwing together a bike like the Beezerker is a nice way to unwind. The Beezerker came together over almost a year of nights, lunch hours and weekends, with Flechtner doing nearly all of it himself. “It’s hard to find like-minded craftsmen who can do the level of work I want.

One like-minded furniture craftsman did stitch up the seat, though, from a thousand-dollar hide imported from Germany. “I wanted to show it’s possible to do more than just saddle leather riveted to a seat pan,” declares Flechtner. “It gives the bike a certain luxury feel.”

Another cool detail is the twist clutch: “I wanted a really clean handlebar, so I converted it to twist clutch. To do that means you need a pulley down at the engine, which required a lot of work, and welding down inside the engine cover, on the intermediate cover. It actually works well; when you grab it, your hand wants to twist back toward you in the usual clutch motion. Pretty cool.”

Lack of a front brake made it easy to conceal the front brake lever, since there isn’t one. Out back, Flechtner found one of those combo sprocket/brake discs for a Harley, machined it down to 520-chain size, then built a mechanical caliper to squeeze it. “I wanted it to have a vague time frame, so I just designed two arms that pivot right in front of the sprocket to squeeze the caliper when the brake pedal is depressed,” he says.

Here’s a lesson: Even a guy as incontrol as Chris Flechtner knows better than to dive into a 40-year-old BSA A65 Twin without a chaperone, so he did shop out the motor work, which was a good thing: The engine builder found a number of “anomalies,” including a pair of modified automobile pistons, which didn’t really belong. Even new, says Flechtner, “the covers are all recycled aluminum. Basically, they threw everything in the pot and recast it, which really causes problems with polishing because there are hard spots and soft spots, empty spots, nooks and crannies. My local polisher has a special compound he calls ‘greasy stuff.’ He burnished this one more than he buffed it. At the end of the day, the engine has the timeless look I was after.”

As for the overall concept behind the bike, Flechtner relates it simply: “My intention was to build a bike that looks like you could take it to the salt flats and just haul ass.” And the emaciatedyet-sleek end product attests to success, even though Beezerker is also streetlegal, with a VIN, title and license plate.

Instead of Bonneville, Flechtner took the bike to the 2010 LA Calendar show in Long Beach, where it won Best in Show. Then it took second place in the Metric World Championships and fifth place in the AMD Freestyle World Championship in Sturgis. And after that, it was off to the Cosmopolitan Hotel in Las Vegas, on consignment in a boutique called “Stitched,” where, we’re told, a buyer may have been located.

Buyer or not, Beezerker did what it was meant to do: Serve notice that Speed Shop Design’s Chris Flechtner is a custom builder to be reckoned with. And now, on to the next thing: a Ducatipowered custom you can see in progress at speedshopdesign.com.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

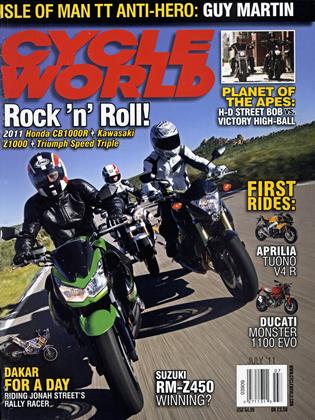

Up FrontThe Mysteries of Grandpa

JULY 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

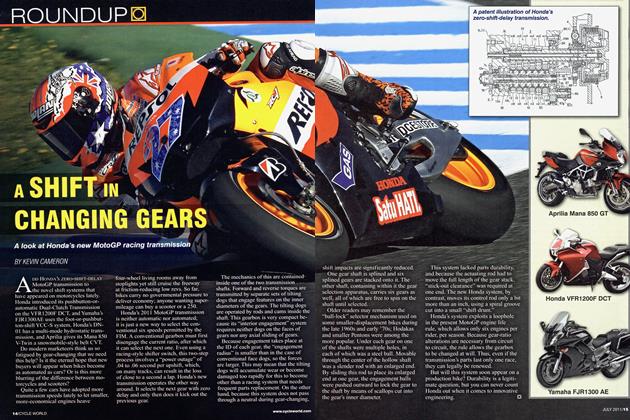

RoundupA Shift In Changing Gears

JULY 2011 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupBmw S600rr

JULY 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

Roundup“chrome” Hawk

JULY 2011 By John Burns -

Roundup

RoundupCycleworld.Com Poll Results

JULY 2011 -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago July 1986

JULY 2011 By Blake Conner