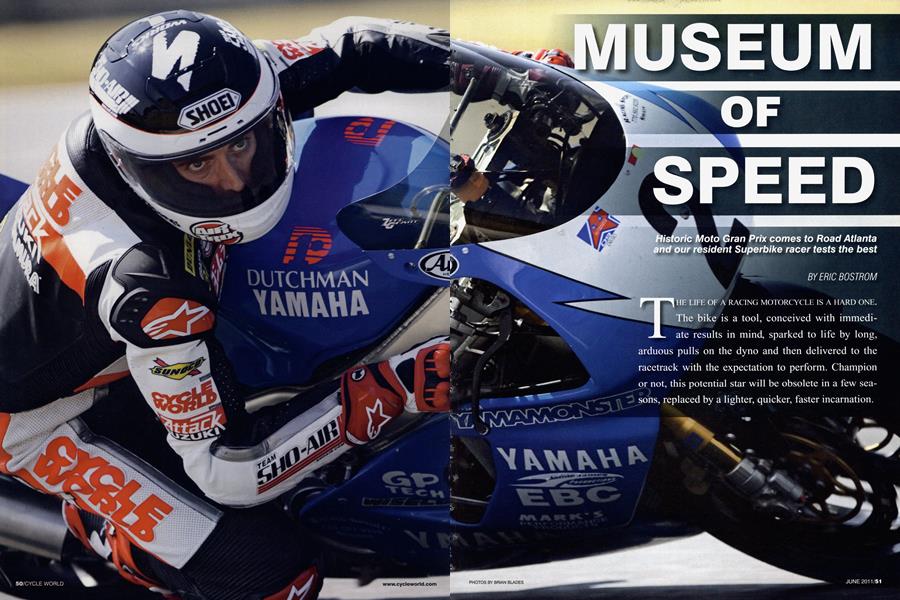

A MUSEUM OF SPEED

Historic Moto Gran Prix comes to Road Atlanta and our resident Superbike racer tests the best

ERIC BOSTROM

THE LIFE OF A RACING MOTORCYCLE IS A HARD ONE. The bike is a tool, conceived with immediate results in mind, sparked to life by long, arduous pulls on the dyno and then delivered to the racetrack with the expectation to perform. Champion or not, this potential star will be obsolete in a few seasons, replaced by a lighter, quicker, faster incarnation.

So, what’s a person to do if he or she proudly owns a piece of two-wheel racing history and is too passionate and loyal to the sport to hide said treasure in a garage or museum, smothered behind glass, its glory nothing more than a memory?

Not only does Bill Brown believe that putting race-bred machines out to pasture is a travesty, he wants to give them someplace to run. A thoroughbred himself, Brown has been bucked off nearly every racebike under the sun, leaving him with a laundry list of aches and a bum hip. Yet in true racer grit, his injuries don’t seem to slow him down.

Brown lives to be at the racetrack on two wheels. He is a collector, but you’re not likely to find a Brough Superior or an Ariel Square Four among his fleet of bikes. He’s a racing purist and a Yamaha devotee blue as blue. His collection spans five glorious decades of racing, and all of his bikes are fitted with numberplates and race rubber.

To keep his dream alive and well, Brown created Historic Moto Gran Prix (HMGP)—“Where History Meets the Road.” Purists to traditionalists, all are welcome, no matter if your motorcycle is stock or heavily modified. You will see beauties in original trim, but they will likely be outrun by bikes that have

been updated to accept modern-day parts for more speed, fun and, yes, a better shot at victory. Brown is thrilled to award his entries with trophies for their on-track efforts.

Brown shares his vision, format and even the racetrack—in this case, Road Atlanta—with Historic Sportscar

Racing (HSR). Brown credits HSR president Steve Simpson for this, asserting that Simpson is always trying to bring relevance and cross promotion to classic motorsports. Classic racing’s Kentucky Derby is the U.K.’s Goodwood Festival, which boasts international competition and exposure. HMGP and HSR are aim-

ing to create a similar type of event here in the States. Just how far they can take it only time will tell. As is true with all antiques, the clock may be on their side.

Unless you are the ultimate motorcycle and automotive historian, you may want to bring along your smartphone to get an idea of what you are seeing as you stroll through the paddock. Better yet, just ask someone. I was shocked that the teams in attendance welcomed spectators with open arms, proudly explaining what was sitting before them. I couldn’t help but think that these guys had outspent top AMA Pro American SuperBike teams just to go club racing!

This laid-back attitude sharply contrasted with the on-track action. I was pleasantly surprised by the aggressive driving and riding antics demonstrated by the owners of these irreplaceable vehicles. So much for gentleman racing! Given the talent pool, I should have known what to expect. After all, you can’t take the race out of the racer. Among the hotshoes in attendance were 1993 World Superbike Champion and five-time Daytona 200 winner Scott Russell and ex-Formula One and sportscar-racing champion Brian Redman.

There were high-profile celebrities, as well, including AC/DC vocalist Brian Johnson, who was racing his 1970 Royale RP2, and his wife, Brenda, at the wheel of her 1957 Austin-Healey Sprite.

During your tour of the paddock, there might be a chance to do something really special, like talk your way into a Rothmans Porsche 962. Designed as a two-seater to meet the rules of the time, it’s more like a one-and-a half-seater, so just wedging my way into this low-slung beast was a challenge. Imagine being strapped into a claustrophobic video game while being subjected to very real g forces and you start to get the feeling. As the crew cinched down the shoulder harness to the point of discomfort and shut the overhead door, I was pretty certain that I wasn’t going anywhere, even, disconcertingly, if the car were to catch fire. Add to all of this the lack of control that I was feeling as a passenger, and owner/driver Johan Woerhiede was in a perfect position to give me a real scare.

Just bringing the tires up to operating temperature was a handful. I was told that at 100 mph, we would be generating enough downforce to stick, upside down, to the ceiling of the conces-

sions building. At slower speeds, however, this caused a stability issue, with Woerhiede fighting the steering wheel on the straightaways. As we accelerated through the gears, the g forces drove me back into my seat as my ears tuned into the whine of the turbo and smooth hum of the transmission. That is all I sensed—or maybe that’s all I had time to sense. Moments later, I was kissing the windshield. Had my belts come loose? Nope, the car just stops that fast. Hey, where can I get brakes like these for my SuperBike? In just a few quick laps, I went from physically not fitting in the car to sloshing around like I was inside a washing machine. Incredible. Now, everything felt right: brute force acceleration followed by neck-choking brakes and cramping lateral forces. I could get used to this video-game-onFast-Forward thing...

My two-wheel part of the weekend began on Bill Brown’s pride and joy: YamaMonster. There is nothing quite like blowing off early-morning haze with raw, unrestricted horsepower. As I turned my right wrist, clarity quickly re-entered my world. Ah, it’s good to be alive! It’s good to be challenged!

YamaMonster, or “Blue Godzilla,” as I affectionately called it, is a factoryframed 1993 Yamaha YZF750 with a full-tilt, 180-plus-horsepower YZF1000based Superbike engine shoehorned into its aluminum frame.

Controlling wheelspin exiting Road Atlanta’s many varying corners is a big job on this beast. Unlike with modern Open-class engines, whose smooth power delivery and electronic traction-control systems allow a heavy throttle hand, when you crack open the carburetor slides on YamaMonster, rear-wheel slides are a certainty, regardless of your speed or gear choice.

Winner of multiple Formula USA titles in the hands of the late Fritz Kling and AMA regular Michael Barnes, the heavily modded inline-Four builds torque quickly and unevenly. It is “manageable” only once you have enough seat time to become intimate with the way the engine delivers power. Man, how bikes have changed!

Fortunately, the chassis is rigid enough that it doesn’t tie itself in knots with the addition of all that brute power. In fact, the bike was surprisingly forgiving in the fast, 100-mph-plus curves.

But you have to respect the throttle in the hairpins! Former AMA Superbike Champion Jamie James put it best: Had YamaMonster been legal for the class, it would have won a lot of Superbike races

in its day. After riding it, I had a big grin on my face.

Another Bill Brown special, the 1988 Yamaha FZR750 has a works chassis and 192-hp 1225cc Superbike Mike-

built engine. Unfortunately,

I didn’t get much time in the saddle to stretch her legs.

Faced with triple-digit ambient temperatures, the motor was running extremely hot, making it feel as if boiling water was pouring onto the arms of my leathers while I was riding. The temp gauge was not working, so I felt it was best to play it safe and not shorten the bike’s life span. I pulled into the pits after just two laps. What I can say is behind all of that heat was a lot of ponies. Too bad I didn’t get to enjoy each and every last one of them.

With its tall, upright seating position, the 1975 Honda CB750 owned by Mike Hodgson looked like some kind of odd dirtbike. The sohc, 836cc four-cylinder motor was linear and strong, and the controls were modern and effective. But hustling this

"Wheelies on the TZ750 were common and thrilling, ecpecially when the front wheel passed a certain point roughly 6 inches above the tarmac. Then, the little machine acted as if it wanted to fly away altogether"

monstrosity through the twisties, working to get it settled and stopped, was a massive chore.

With all of the leverage available from the wide bar,

I had to be very delicate with steering inputs, especially on the straightaways, where the bike seemed hell-bent on weaving. I flat ran out of courage attempting to hold the throttle wide-open down the back stretch, fearing what might happen next if the weave became a wobble.

It’s amazing to me that these strange-looking machines brought along some of America’s finest racing talent. Once again, I’m reminded of the bravado that was required to be on the pioneering end of our sport.

Fitting behind the bubble of GP Tech’s Honda NSR500V—think 250cc Grand Prix bike on steroids—was out of the question for me. Clearly intended to combat wheelies, the riding position was so far forward that I was hunched over the front tire and my face was shoved into the tachometer. Only an alien could fit on this thing!

Sold briefly by Honda during the mid-Nineties, this two-stroke V-Twin had zero engine braking, and the twin-spar aluminum chassis was ultra-rigid. Coupling that with the extreme riding position, what I got was a nervous, unforgiving ride. Total commitment was required at all times.

While I had fun wheelying around Road Atlanta on this “production” GP bike, actually racing it would be altogether different. I imagine holding my breath while being whipped around at the end of a yo-yo, trying to make a corner-speed advantage over the four-cylinder competition. Frightening!

Finally, John Concklin’s ex-Russ Paulk 1977 Yamaha TZ750D 0W31—the broodmare sire of modem racing. My first impression of the TZ was, “This thing is a gamechanger!” Okay, I had the advantage of modem brakes and

tires, but this thoroughbred surpassed all of my expectations. I’ve heard stories of light-switch power delivery, blinding speed and a noodle of a chassis. With all this anticipation, I was nearly let down to learn just how docile the TZ actually is.

The four-cylinder twostroke engine created reasonable torque at 7500 rpm, giving me just enough time to prepare for the hard hit that kicked in at roughly 9000 rpm. A quick run through the gears onto Road Atlanta’s high-speed back straightaway proved stability was not an issue, even when wheelying over crested Turn 11.

Because the chassis was quick to settle, transitions came with ease and accuracy. Stopping on the lightweight TZ was no drama, either; light pressure on the back brake aided corner entry, and the bike rolled into the corner perfectly. Exit wheelies were common and thrilling, especially when the front wheel passed a certain point roughly 6 inches above the tarmac. Then, the little machine acted as if it wanted to fly away altogether. Learning this trait would be critical if I were to race this bike because looping out is never cool.

In retrospect, I imagine this potent racer on decades-old rubber technology would be a real handful. But the TZ’s winning track record speaks for itself. Both potent and fim to ride, these bikes raised the bar. I couldn’t get the grin off my face for hours.

Historic Sportscar Racing and Historic Moto Gran Prix are targeting baby boomers who want to relive their youth. After a weekend living this incredible mix of camaraderie, competition and nostalgia, experiencing the thoroughbred twoand four-wheel machines of yesteryear getting another shot at stretching their legs,

I say don’t forget to include me! If Brown and Simpson have their way, motorsports museums with their lifeless displays may soon be a thing of the past. Let them run. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontA Japan In Need

JUNE 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupAmerican Sport-Tourer

JUNE 2011 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupZero Motorcycles Gets Seriou

JUNE 2011 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

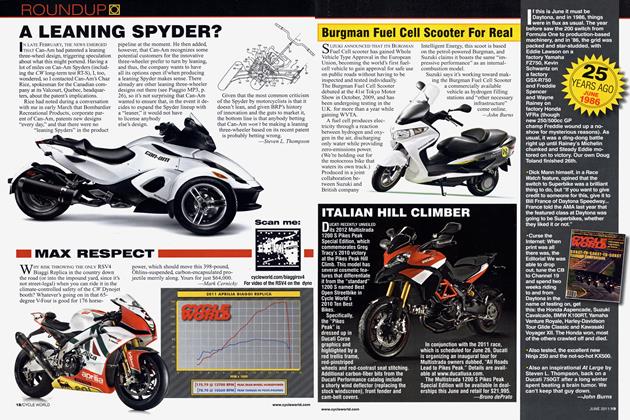

RoundupA Leaning Spyder?

JUNE 2011 By Steven L. Thompson -

Roundup

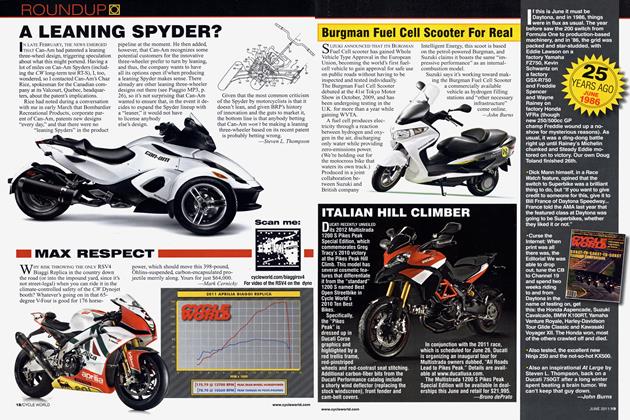

RoundupMax Respect

JUNE 2011 By Mark Cernicky -

Roundup

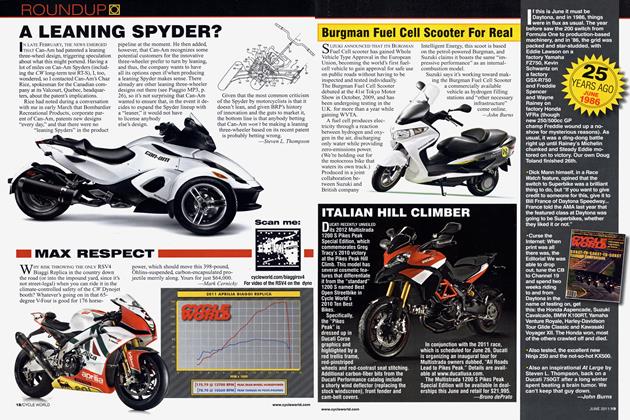

RoundupBurgman Fuel Cell Scooter For Real

JUNE 2011 By John Burns