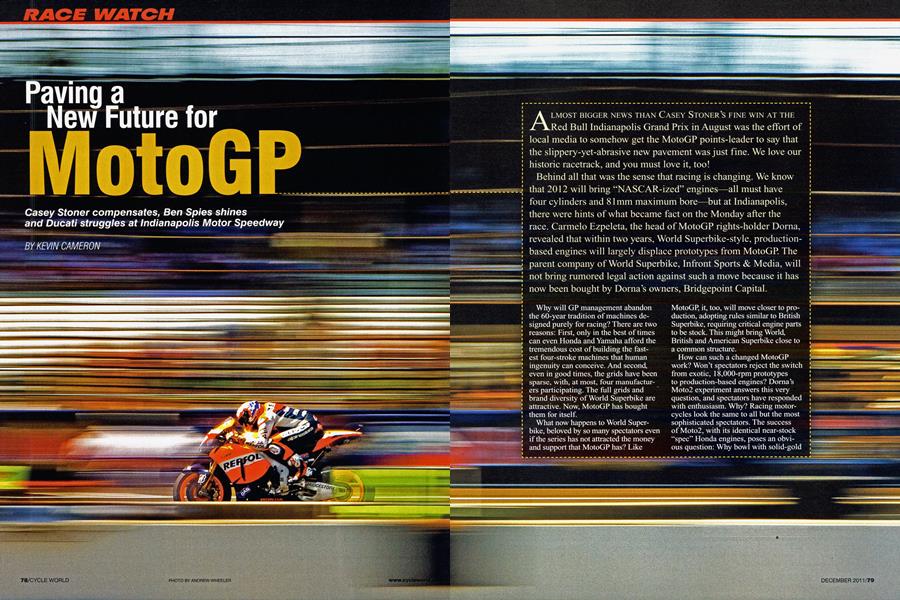

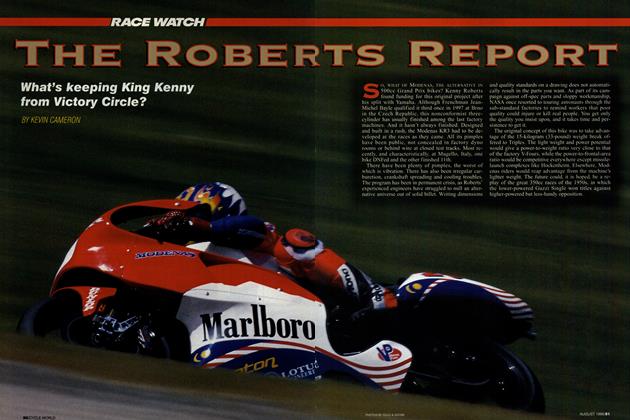

Paving a New Future for MotoGP

RACE WATCH

Casey Stoner compensates, Ben Spies shines and Ducati struggles at Indianapolis Motor Speedway

KEVIN CAMERON

ALMOST BIGGER NEWS THAN CASEY STONER’S FINE WIN AT THE Red Bull Indianapolis Grand Prix in August was the effort of local media to somehow get the MotoGP points-leader to say that the slippery-yet-abrasive new pavement was just fine. We love our historic racetrack, and you must love it, too!

Behind all that was the sense that racing is changing. We know that 2012 will bring “NASCAR-ized” engines—all must have four cylinders and 81mm maximum bore—but at Indianapolis, there were hints of what became fact on the Monday after the race. Carmelo Ezpeleta, the head of MotoGP rights-holder Dorna, revealed that within two years, World Superbike-style, productionbased engines will largely displace prototypes from MotoGP. The parent company of World Superbike, Infront Sports & Media, will not bring rumored legal action against such a move because it has now been bought by Dorna’s owners, Bridgepoint Capital.

Why will GP management abandon the 60-year tradition of machines designed purely for racing? There are two reasons: First, only in the best of times can even Honda and Yamaha afford the tremendous cost of building the fastest four-stroke machines that human ingenuity can conceive. And second, even in good times, the grids have been sparse, with, at most, four manufacturers participating. The full grids and brand diversity of World Superbike are attractive. Now, MotoGP has bought them for itself.

What now happens to World Superbike, beloved by so many spectators even if the series has not attracted the money and support that MotoGP has? Like

MotoGP, it, too, will move closer to production, adopting rules similar to British Superbike, requiring critical engine parts to be stock. This might bring World, British and American Superbike close to a common structure.

How can such a changed MotoGP work? Won’t spectators reject the switch from exotic, 18,000-rpm prototypes to production-based engines? Dorna’s Moto2 experiment answers this very question, and spectators have responded with enthusiasm. Why? Racing motorcycles look the same to all but the most sophisticated spectators. The success of Moto2, with its identical near-stock “spec” Honda engines, poses an obvious question: Why bowl with solid-gold bowling balls when the game is just as exciting with plastic ones?

After first practice Friday morning at Indianapolis, every rider was exclaiming at the slippery, new pavement from Turn 5 to Turn 16. Walking around the circuit, I could see the normal MotoGP extreme angles of lean in the first four comers, but elsewhere, bikes were leaned over to only 45 degrees, indicating about half of normal grip. After second practice, riders were saying that tire distress was also extreme. Oily matter from the new pavement, plus visible brown dust, was making the surface slippery. But that surface was also highly abrasive with the sharp points of its gravel component still sticking up. The result was tire “graining”—wear in the form of beach-like parallel lines on the tire surface, indicative of insufficient compound strength. Yet this was occurring even with hard Bridgestone front tires. Grip has several components: molecular attraction, mechanical interlock and hysteresis. That dust and oily matter were negating molecular attraction, allowing tires to slide across the sharp new texture, tearing even the hardest tires.

The Yamahas with their smooth power seemed at first to have an advantage, with Ben Spies, Jorge Lorenzo and Colin Edwards at or near the front. As mbber was laid down and dust blown out of the texture, a single line with better grip developed, but off that line, there was nothing. This forced most passing to take place into Turn 1.

As more grip appeared, the Hondas demonstrated their season-dominating strength, and Stoner could show why he is the points leader. When challenged to discuss the slippery places on the track, he listed them all, corner-by-corner.

This reveals why roadracing is an intelligence test and not a dare. In the race, Stoner would remain aware of every low-grip spot and smoothly integrate that knowledge into his line and throttle application.

Don’t electronics now handle all that? Stoner told the press that he needs manual control to do what he does, and used traction control only in Turns 5, 10 and 12.

As he had said earlier, “I ride each bike as it needs to be ridden.” That means, for example, that when he was on the Ducati, which understeered, or “pushed,” he devised ways to induce oversteer. He finds a way, he adapts and he makes the machine do the job. This doesn’t mean no electronics; these bikes have powerbandsmoothing, GPS-linked anti-wheelie and fuel-consumption management—all electronic. On Friday, Stoner said, “We destroyed a hard front in four laps,” but as events unfolded, he studied how to extend front tire life.

Certain things stood out: One was Stoner’s rapid downshifts, which sounded almost automated. Another was the difference in anti-wheelie systems. The Yamahas’ front wheels hovered an inch off the pavement, but Ducati’s software acted suddenly, slapping down a rising wheel.

Indianapolis was toughest on Ducati, compounding troubles it has had all season. Valentino Rossi’s crew chief, Jeremy Burgess, pointed to lack of front-end feel and inability to finish the corner. Lack of feel means little warning that the rider is nearing the limit. Inability to finish the corner means that

the rider cannot accelerate competitively while holding his chosen line.

Because the Ducati has significantly less weight up front than other makes, it was harder for Rossi and teammate Nicky Hayden to give the Bridgestone fronts what they require, to load them by weight transfer, squashing out a big footprint that grips. On the slippery pavement, the attempt produced little weight transfer, plus more sliding, tire abrasion and tire distress. In the race, Hayden, the only rider on a medium front, got away fourth. After Lap 10, he went backward, eventually finishing 14th. Rossi ran off the track in the race—problems with downshifting Ducati’s new “zero-delay” gearbox— but came back to finish 10th.

Can Ducati recover? Burgess noted that the carbon front structure is really too short to incorporate much flexibility, and the rumor mill whispered that FTR, a British chassis builder, has completed a conventional twin-beam aluminum chassis for Ducati to test. Ducati den☺ied this but such a machine was tested two weeks later at Mugello in Italy. Stiffness has been softened by moving front-wheel bearings closer together and by using ball instead of taper-roller steering-head bearings. Alternative front structures have been built. Official talkers say, “We will do whatever it takes,” but at the same time, they deny that Ducati’s 90-degree Vee engine configuration has reached its limit in terms of achieving the forward weight MotoGP steering requires.

They tread a fine line here. For sophisticated enthusiasts, Ducati is a group of engineers producing the best possible solutions. For others, Ducati is just a collection of obvious “signature” features: desmodromic valves, the 90-degree Vee engine and Italian style. If management takes the latter view, future Ducati motorcycles may be designed not by their engineers but by their fans.

Burgess compared Ducati’s present situation with that of Michelin in 2007. That company had gone down a developmental road of ever-narrower tire-operating temperature range and could not then leap to a similar sophistication in making tires with a wide range. It would have to go back to the beginning and push R&D in a new direction. Ducati sought light weight and high stiffness from its Vincent-style carbon chassis, which uses the engine as the major structural member. Yet carbon is so stiff that providing the lateral flex necessary for front-end feel has eluded engineers.

Those aforementioned official talkers further imply they will, like Civil War General U.S. Grant, “fight it out on this line if it takes all summer.” Could be a problem! If the process is too slow, people close to Rossi fear he may lose interest.

The 90-degree Vee engine is a separate issue. The wider an engine’s Vee angle, the farther back its crankcase and gearbox mass is pushed by the need to keep the front tire from hitting the front cambox. Rotating an existing engine back, while keeping the gearbox sprocket where suspension geometry requires it to be, means raising the engine excessively—or making a new one. The obvious solution is to narrow the Vee angle, as Honda and Suzuki have done, allowing forward weight bias, a short wheelbase and best rear suspension geometry to coexist. The danger in doing this is the problem Harley-Davidson would face if it stopped making air-cooled pushrod engines with a 45-degree Vee angle: the anger of traditionalists.

Some suggest Ducati should quit MotoGP and return to World Superbike, where Carlos Checa leads the series on a private Ducati. What do you suggest?

Tom Houseworth, crew chief for Ben Spies, third at Indy after starting second, said of track conditions, “We pretty much Íét them come to us.” This meant that rather than trying to adapt the bike to the increasing grip, they used their normal setup. The track “came good” as conditions became more normal. After the race, Spies said, “It was hard to concentrate. There were hundreds of balls of rubber in every corner.”

No matter what the conditions, riders come to the line and race. The problems of the day shook out in the final order: Stoner, Dani Pedrosa, Spies, Lorenzo and third Repsol Honda teamster Andrea Dovizioso.

As for the future? The Brickyard’s contract with MotoGP has been extended through 2014. And if racing ever needs a downward displacement “reset” to better appeal to emerging markets, Dorna’s Moto3—a 250cc four-stroke Single class—begins next year. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontHome At Last

DECEMBER 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

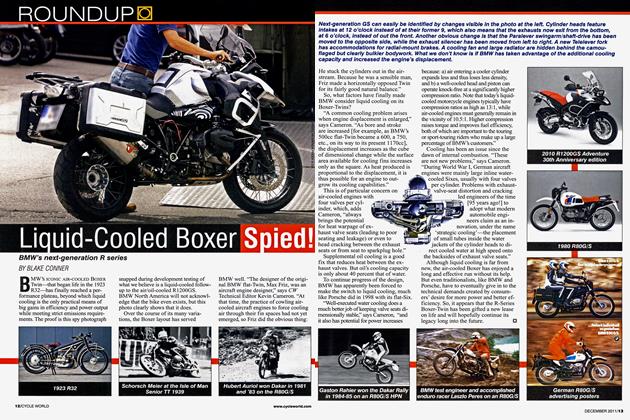

RoundupLiquid-Cooled Boxer Spied!

DECEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago December 1986

DECEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

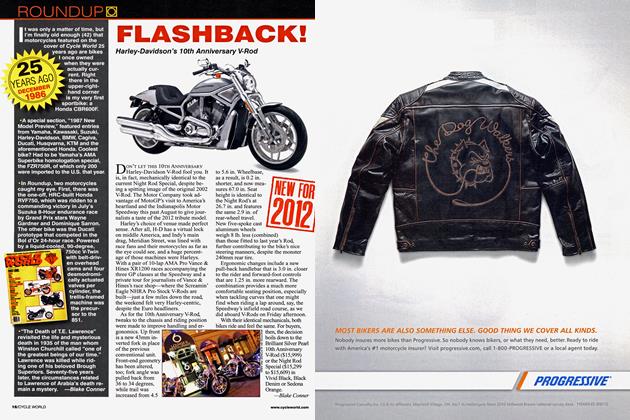

RoundupFlash Back!

DECEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

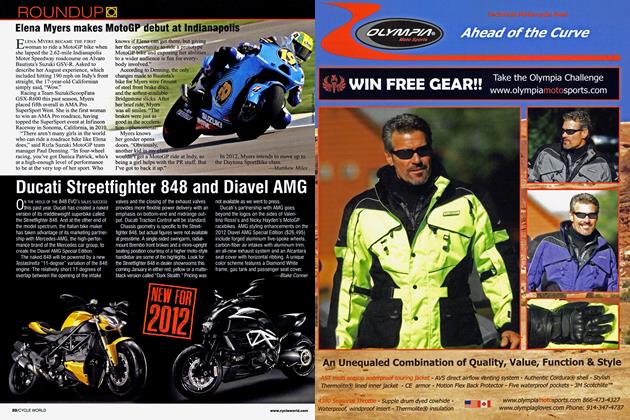

RoundupElena Myers Makes Motogp Debut At Indianapolis

DECEMBER 2011 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupDucati Streetfighter 848 And Diavel Amg

DECEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner