TDC

Sociology of Motorcycles

KEVIN CAMERON

WHEN MY DAD WAS AT DEPAUW University in Indiana about 1930, a classmate known as Rody Rodenberg always had a motorcycle. Then, as now, the Great Depression was making college students that doubted their all-nighters and just-in-time term papers were going to win them better jobs. Rodenberg boldly quit college and went motorcycle racing. He was still on Daytona entry lists into the late 1940s.

Today, big-time CEOs ride the right sort of motorcycle, but back then, if your ride had two wheels, you were a tearaway-just plain crazy, deserving of any bad thing that happened to you. A cousin had a bike (a great big thing with Buick tires on it, looking like it couldn't fall over even with the sidestand up), scared himself on it and sold it. Six hundred pounds with 6-inch drum brakes lined with linoleum would scare me, too.

When I went off to college and bought my first bike, it was the classic newbie POS, and I should have been embarrassed to sit on it. It was a BSA Bantam, making about the same power as a decent belt sander, but my parents’ reaction was, “Well! Of course, you’ll have to sell it!” I didn’t sell and I didn’t die, and here I am to tell the tale.

When I was in high school, anyone could buy an old bike for $50, fix it up a bit and try to learn to ride. Carburetors on that kind of bam bike were iron and their floats varnished cork—some improvisation required. Becoming competent was similar to how I learned to ride a bicycle: Roll the thing up a hill, get on and, while coasting down, experiment with different plans for not falling over. After falling over, repeat. One afternoon did the trick.

Today, insurance outfits advertise their motorcycle policies, but my experience in Massachusetts was the Assigned Risk Bureau. Nobody wanted to insure those crazy motorcyclists, but the state had to cater for them. The Motor Vehicle people sent you to the nearest insurance office with your documents. There, a bored young woman would perfunctorily stamp them REJECTED. Back at Motor Vehicle, another clerk who wished he/ she were someplace else now assigned you to whichever luckless underwriter

was next on their list, and that outfit was required by law to write you. Fuel, spark, compression and license plates!

For a time in the 1960s, it seemed that every other motorcycle mechanic in the Boston area was taking a year off from a PhD program. Roadracing was for intellectuals, it seemed. And controversial. The real motorcyclists let you know that if you weren’t foot down, turning left while steering right, you were of questionable gender. Gray flattop haircuts ruled, along with big old shoes suitable for construction work.

Through the ’60s, the Japanese trained millions to ride on their inoffensive stairway to motorcycling heaven. Alfred P. Sloan at GM had taught the world that if you offered an Olds that was just a bit fancier and more expensive than the Chevrolet, people would live on 1200 calories a day just to make the payments. And so it went from 50cc step-through to sporty, stylish Honda 90 to 125s and 150s. Onward! 250s, 305s, 350s, a 450! In the process, millions got over cyclophobia and the conviction that bikes give you tattoos. The British, who, with a bit of market research, could have been preparing to supply the onrushing U.S. demand, were instead stuck trying to make bored-out 1950s 500s on clappedout 1920s tooling. If truth be told, Bob McNamara was trying to do something similar over at Ford. That was an era for making the numbers look good.

Then the deluge! The 1970s were the Decade of the Motorcycle. Fun for all, easy terms, everybody’s doing it—it will always be like this.

The 1980s corrected those serious errors. Young people aspired to become tastefully dressed securities analysts in 5-series BMWs, and anything containing an element of risk was anathema.

Industrial jobs went abroad, sapping the buying power of the 18-to-24s. Buttoneddown types sneaked glances at motorcycles, but the time was not yet ripe.

In the 1990s, motorcycles went upscale, chasing the people who could still afford them. Complete change. CEOs tasted the total freedom of the Open Road by shipping their bikes to Sturgis and flying First Class to meet them. Quality time on two wheels. Much nonsense was uttered about “kinaesthetic art.” Really nice coffee tables were littered with colorful copies of Big Twin and the Guggenheim show catalog. Bottom line: It was now okay to ride a motorcycle even if you could easily afford it. Harley grew rich on repackaged rebellion and sumptuous paint and plating. Ducatis were art, and if you rode one, there was the added possibility that, like Carl Fogarty, you could weld stainless by just staring at it.

Fookin’ good! Off we flew, Cycle World staffers, to the great motorcycle shows in Munich. So much new stuff! But history teaches that when the displacement of the most-sought-after motorcycles reaches or exceeds 1 OOOcc, economic collapse is imminent. Economics did collapse, and here we are, hoping for the best.

What is the future of motorcycling? The most wonderful opinions can be heard. Sportbikes replaced by 550-pound adventure cycles! Maxi-scooters herald a new age of functional practicality! Electro-bikes with optional welding cables in case of mishap (subs had ’em, why not?). Or will it be two-wheel austerity on survivalist Singles propelled by gases liberated from household compost?

No matter what novelties are to come, someone would have to ride them. That seems in doubt if everyone is growing pale at the game console, tweeting a laconic 21st-century “Remembrance of Things Past” or chalking up the 300th “friend” on Medium-of-the-Month. Shall I physically buy an $11,000 600, a low-priced $500 helmet and struggle through licensing when ScooterShooter and Grand Theft Motorbike beckon from their quirky little screen icons? Or, even better, from the succession of handhelds whose market dominance is so transient that there isn’t time to buy them in stores—they come FedEx automatically from TrendTrippers, one after another.

Then there’s this: Fun never goes out of style, and neither does function. If the New World needs cheap transportation, motorcycles can supply it. If prosperity returns, shiny as ever, motorbikes will deliver their share of the enjoyment. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontBattle of the Dust

OCTOBER 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

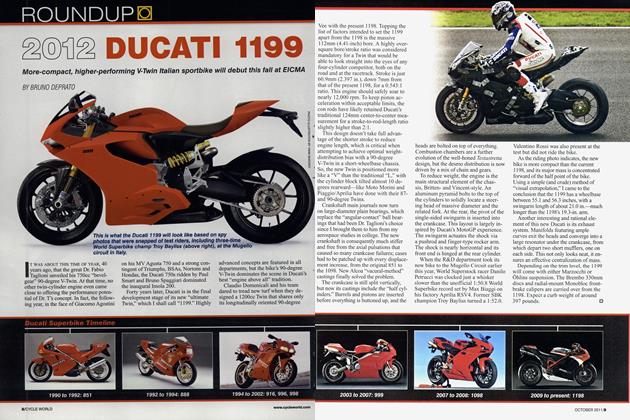

Roundup2012 Ducati 1199

OCTOBER 2011 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

RoundupHonda's Nsf250r Moto3 Contender

OCTOBER 2011 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

Roundup2012 Mv Agusta F3 Serie Oro

OCTOBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

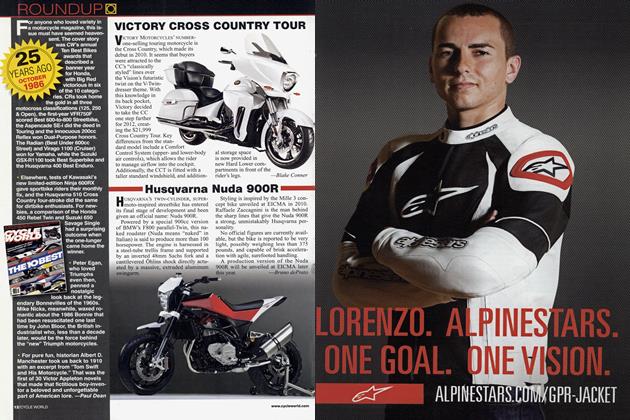

Roundup25 Years Ago October 1986

OCTOBER 2011 By Paul Dean -

Roundup

RoundupVictory Cross Country Tour

OCTOBER 2011 By Blake Conner