Real Racing

RACE WATCH

World Superbike returns to Utah

KEVIN CAMERON

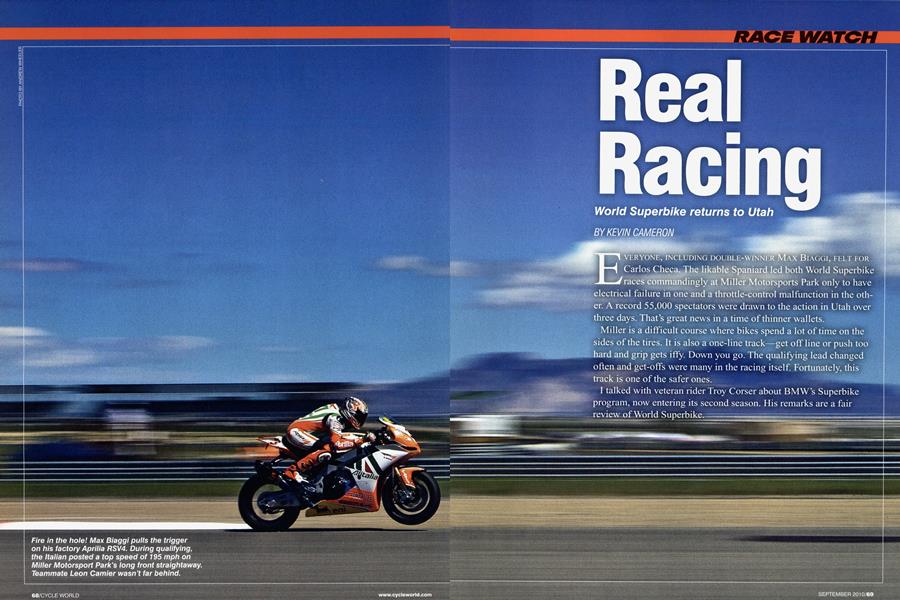

EVERYONE, INCLUDING DOUBLE-WINNER MAX BIAGGI, FELT FOR Carlos Checa. The likable Spaniard led both World Superbike races commandingly at Miller Motorsports Park only to have electrical failure in one and a throttle-control malfunction in the other. A record 55,000 spectators were drawn to the action in Utah over three days. That's great news in a time of thinner wallets.

Miller is a difficult course where bikes spend a lot of time on the sides of the tires. It is also a one-line track—get offline or push too hard and grip gets iffy. Down you go. The qualifying lead changed often and get-offs were many in the racing itself. Fortunately, this track is one of the safer ones. I talked with veteran rider Troy Corser about BMW’s Superbike program, now entering its second season. His remarks are a fair review of World Superbike

“Last year, we got a lot of information for the engineers, and we’ve done a lot of testing since the start of this year,” he said. “They made a lot of new stuff for us to try.

“The Ducatis have been better than the four cylinders—smoother, easier to win races on. So, Ducati was three or four years ahead of the Japanese. Now, the Ducati is as good as it can get and the others have caught up and actually passed them.

“You can only turn a Twin so hard before things start to break, but now the four cylinders are turning 20003000 more revs than they were a few years ago. Ducati can make more power, but they’ll have to change things [there’s talk of a shorter-stroke, 112.0 x 60.8mm Twin to come].”

BMW hired Corser for the breadth of his experience. “When I jumped off [the Aprilia], the [Foggy Petronas] Triple was the most radical,” he said. “Then the Suzuki was solid and stable. After that, the Yamaha—not this new YZF-R1 but the one before it—was nervous, with sharp power, really aggressive. So going from the Yamaha to the BMW wasn’t such a big change. When we turned it down to be more like the Suzuki, the times began to come.”

Power alone can’t win races, but Biaggi won them both on the Aprilia RSV4, recording the highest top speed of the weekend: 195 mph. The BMW is powerful, too, but to make it hook up, it is so detuned that top speed is hidden. And the extra power normally unleashed for qualifying just magnified the BMW’s defects. This is the reverse of traditional development, in which a team builds a “one-lap motorcycle” first, which qualifies well but eats its tires in races. Corser was second for a time in Race 2—very encouraging—but went backward in both races as the “natural engine” overcame the electronic measures in place to tame it. The Yamahas remain fast; new British recruit Cal Crutchlow was third in Race 2.

“I talked with Jonathan Rea, the slender, gangly Englishman on the Ten Kate Monda. His opinions had teeth...”

Comments from teammate James Toseland about the Rls were fascinating. When I asked him if the “crossplane” crank gave the bike special characteristics, he ignored that question to talk about its torque curve, saying, “It pulls so hard down low that you

you

really can’t use it. We’re gearing to spin the engine.”

I asked, “Do you mean like Mick Doohan did with the Honda NSR500s—gearing to ride in the falling-torque part of the curve?”

“Exactly.”

About tires, Toseland said, “With the Bridgestones in MotoGP, you spend three laps at the start warming up the tires, and then they stay like that for 20 laps. But on the Pirellis (the spec tire in SBK), they’re

good for about three laps and then they start going down steadily after that.” Toseland gave this comparison to show how different are the conditions that electronics must handle in the two series. “In MotoGP, we had traction monitoring (Valentino Rossi’s engineer Jeremy Burgess called it “mu-learning”), and it’s automatic. The fuel conservation is turned off for qualifying and you go a half-second faster than you can in the race.”

Electronics are simpler in SBK. Corser said, “Yes, we have GPS capability that could give us different

settings for each track segment. But it takes so long to set that up and it’s so easy to go down a dead-end street that we stick to basics.”

Checa, who doubled at MMP in 2008, led both 2010 races with apparent ease on his privately entered Althea Racing Ducati. He took big, smooth lines and clearly has the knack of conserving tires while going very fast. Lots of others clearly did not; the BMWs’ tires faded, and many riders tipped over. On a one-line track, the race leader has all the choices.

I talked with Jonathan Rea, the slender, gangly Englishman on the Ten Kate Honda. His opinions had teeth: “The Japanese manufacturers have built streetbikes and homologated them for racing. But the Europeans—Aprilia, BMW and Ducati—have built racebikes and productionized them for sale. I’d love it if I could get a 3-kilogram handout by sandbagging.”

Rea was referring to the weight reduction given Ducati because of its lackluster showing thus far this season. SBK boss Paolo Flammini referred to this in his address to the media by saying, “This is the first time we have used this control.”

Yet Flammini respects the problem of policing electronics. “We don’t want rules that generate suspects in the paddock, but there is no problem now—we have two privateers on the front row [Checa and Shane Byrne].”

I went to talk with Ducati’s new team manager, Ernesto Marinelli, who replaces Davide Tardozzi, hired away to BMW.

I asked him about the classic problem of how to extract a balanced set-up solution from the “tower of Babel”—the data, engine, suspension and tire technicians attached to each rider.

“There is a structure for this,” he replied.

Such formality is what you would expect from the company with the most experience in Superbike racing.

I also had the opportunity to speak with Ronald Ten Kate, manager of the Honda team. I asked him, too, about getting a fast, durable setup from many technicians.

“In our shop, everyone must learn all the jobs,” he said. “Computer technicians must know how to operate a CNC center. A suspension man must know how to weld. Then we understand each others’ problems better.”

"The Ten Kate team has risen by sheer merit, building fast bikes, selling the parts they design and, now, operating Honda's SBK team. Engineering!"

The Ten Kate team has risen by sheer merit, building fast bikes, selling the parts they design and, now, operating Honda’s SBK team. Engineering!

Some see BMW clearly benefiting from Tardozzi’s experience; he is, after all, a winning veteran manager. But some see him as the classic consultant hired for his prestige only to be > ignored. Last year, the BMWs “spun away all their power,” and this year, their top speeds are down as the team tries to give its riders no more power than they can use. Yet they still eat their tires and go backward in races.

I was introduced to Carlo Fiorani, Honda’s head of racing activities for Europe. I asked him about racing’s relationship to sales. Will the present trend take us away from equal roles for machines and riders to some future state in which fans are excited only about the excitement? Does Moto2, with its spec engine, point to the future?

“Is it enough to sell only excitement?” he responded. “When I first came to Honda, I was sure we should concentrate more on marketing, but I was wrong. Honda is a product-centered company, and this is successful because people must seek function in products.

So racing, to be supported by the manufacturers, must also say something positive about the product.

“In the next few years, we will see what direction racing will take, and how the computer’s virtual view of motorsport will affect racing.”

Fiorani knows that a person with dozens of Facebook friends may prefer not to make eye contact with a real person, and that a child, given a dirtbike, may prefer the virtual keyboard version> because it is so easily controlled.

One much-discussed nugget is Aprilia’s use of an EXUP-like exhaust valve to generate controllable engine braking on the machine of Leon Camier (second to Biaggi in Race 2). Although engine braking is a problem for most riders, Camier’s style requires it. Presumably, the system cuts fuel injection during braking, closes the valve at the end of the header pipes and then modulates engine braking by turning the throttles—a “Jake Brake” for bikes.

Engines come back on-throttle with a bang after a fuel cut, evidently because the walls of the intake pipes, normally wet with fuel downstream of the injectors, dry up. Adding the extra fuel to replace this at throttle-up then produces a jolt that upsets acceleration. But it is only a software matter to bring in the cylinders one at a time, cutting the jolt by three-quarters.

Speed of service is likewise an issue, especially now that shorter race programs are under discussion as a means of saving teams money (discussed at a manufacturer meeting Sunday night). The faster you can change a fork, shock or an engine, the more setup answers you can get from limited practice time. In the few minutes I had with Marinelli in the Ducati garage, mechanics changed one bike’s fork. Aprilia’s easy-to-alter steering head is > said to allow changes of angle or foreand-aft position to be made in less than 10 minutes.

Some worry that MotoGP’s 2012 plan to permit production-based lOOOcc engines to compete with 800 and lOOOcc prototypes schemes to entice manufacturers to put 100 percent into MotoGP and zero into SBK. In economic hard times, the big fish seek market share, and this could be an example.

There are smaller concerns: Teams have felt since Aprilia entered the series that its MotoGP-style gear-driven cams should earn them a weight penalty (with gear drive, cam timing remains constant through races, rather than retarding slightly as cam chains wear at their joints). But complaints are not loud. Who can complain when so many makes are in contention? Presently, an Aprilia is leading the series with a Suzuki close behind, then a Honda, two Ducatis, a Yamaha and a BMW after them. Manufacturers, teams and spectators agree this is good (and cost-effective) racing.

How is it achieved? Flammini told us it is the “continuous relationship with manufacturers and teams,” by which racing at the desired level is made affordable and fair.

These riders race as hard as their tires will let them—there is no pointless 21-liter MotoGP fuel limit to sap their power. World Superbike is still real racing, not the Mobil Economy Run.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

SEPTEMBER 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupRound And Black

SEPTEMBER 2010 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupMagpul Ronin

SEPTEMBER 2010 By John Burns -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago September 1985

SEPTEMBER 2010 By Paul Dean -

Roundup

RoundupInstant Video!

SEPTEMBER 2010 -

Roundup

RoundupMarzocchi Rebounds

SEPTEMBER 2010 By Bruno Deprato