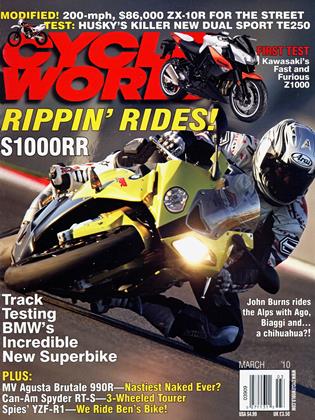

ADRENALINE INJECTION

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Kawasaki steps up its game with the all-new Z1000

BLAKE CONNER

"NOT ANOTHER NAKED.” THAT WAS THE FIRST RESPONSE from Kawasaki’s U.S. product-planning department when the Japanese home office asked how many Z1000s the American market could absorb. Lack of sales success with previous standards meant Kawasaki over here wasn’t sure it wanted anything to do with the new bike, especially in the current economic environment. Now, with the Z1000 obviously green-lighted, something must have changed at the Irvine, California, headquarters. So what was the swing factor?

“The Z1000 is one of those bikes that is very hard to put into words,” said Kawasaki Product Manager Karl Edmondson. “No matter what is said in a PowerPoint presentation or in the press kit, it’s one of those bikes you just have to go out and rider

And that is exactly what they did. A little bit of seat time in Japan helped the Orange County crew change their minds, primarily because of the ZlOOO’s performance—terrific performance, actually.

“One of the issues with standard bikes,” Edmondson explained, “is that they tend to have standard power, standard suspension, standard braking performance and standard handling and turning ability. The perception in the marketplace is that in order to get the best styling, engine performance, handling and suspension, you have to buy a premium-class sportbike like a ZX-10R or ZX-6R. The problem is that the number of riders capable of getting the most out of a supersport bike is very limited. These models are so focused on performance that they’ve become full-on racebikes that are just barely street legal. The fun factor has kind of gone away in regard to the streetability of some of these motorcycles.” To accomplish its goals, Kawasaki completely scrapped the previous Z1000 and started from scratch. The design objectives were two-pronged: “First, we wanted to have a visual impact and get away from the ‘standard’ or ‘naked’ categories, so it wasn’t just a typical generic bike; we wanted to give it a really sporty image,” Edmondson said. “The second goal was to have a riding impact, to give it supersportlike engine performance and handling, and to give it the type of feedback you get when riding a sportbike, but do it in a package that is more natural and comfortable for everyday street riding.”

A good place to start was with the engine, which was designed specifically for the Z. It’s not based on the ZX-IOR or the previous Z1000 motors; it’s an all-new mill sharing virtually nothing with others in the family. The liquid-cooled, dohc, 16-valve inline-Four displaces I043cc from 77.0 x 56.0mm bore and stroke dimensions. The engine’s physical layout (which places the crankshaft and transmission shafts on the same horizontal plane and are not triangulated, as has become the repli-racer norm) was specified so that it would quickly be identifiable as a Z1000.

Engineers wanted high performance, but the power also had to be accessible to a broad range of riders and be fun for real-world riding conditions. This meant torque and throttle response would take precedent over top-end horsepower. The engine had to be smooth, as well, because many riders complained about excessive engine vibration on the previous models.

To get the longer stroke deemed necessary for torque production while maintaining a compact engine size, the crankshaft was lowered in the case to keep cylinder height similar to that of the previous model. A gear-driven secondary balancer was added to help quell vibration that might find its way to the rider via the three solid engine-attachment points (the fourth is rubber).

Fueling is handled by a bank of 38mm, single-injector Keihin downdraft throttle bodies, which incorporate ovaltype sub-throttles controlled by the ECU; the rider’s right wrist still opens the primaries. Cool air is inducted from a pair of intakes on the upper sides of the mini-fairings through the frame and into an airbox, which employs an intake-sound-enhancing resonator (think blowing across the top of a bottle) for a throaty growl.

Much will be said about the exhaust system’s love-it-orhate-it styling, but in technical terms, it is 1.5 pounds lighter than the one used on the previous Z1000, while the quadstyle mufflers are shorter and require less volume (due to a large pre-chamber under the engine), contributing to better mass centralization. Three catalyzers are incorporated into the system; there is no O2 sensor.

After we looked at the power curves obtained on the Cycle World dyno, it became apparent that the engineers accomplished their torque-rich mission. An amazingly linear horsepower curve is complemented by a flat torque curve that gets an added bump in production around 7000 rpm.

Out on the road, this tractability and flexibility mean that the engine is always there for you. “A nice clutch and good fuel mapping make snappy off-the-line launches easy to execute,” said Editor-in-Chief Mark Hoyer. “And, man, is there torque!”

And you won’t have to wait long for power to build when passing a car, as the relatively short gearing has the engine spinning just below peak torque. From about 6000 rpm on up, just snap open the throttle and cars disappear in the mirrors. Of course, a downshift at that same point puts the revs right in the fattest part of the curve and makes delivery even more potent.

With Road Test Editor Don Canet at the controls, the Z ripped off a smoking 10.38-second quarter-mile, getting out of the hole with authority but falling off a bit in the upper echelons of the rev range, which is no surprise considering the engine’s design intent. On the tight, twisty, crested roads encountered during the Cambria, California, press introduction, the ZIOOO was a blast. Rises in the terrain invited the rider to loft the front wheel in easy, controlled power wheelies, the low gearing allowing this to be done in any of the first four cogs.

Performance doesn’t come without civility, either. “Engine vibration is mightily reduced from the level produced by the previous Z1000 and, particularly, the buzzy first-gen Zed,” said Hoyer. “This new one is a pretty smoothrunning inline-Four. Not quite as refined as Kawasaki’s own ZX-14 but very good.” Complaints about engine performance were few, but our testers did notice a slight hesitation from the injection system. “When picking up the throttle on corner exits, there was a slight delay, a non-intuitive degree of torque for the throttle position selected,” Hoyer said. “It almost feels like a computer-controlled-secondary-butterfly thing, sort of similar to the artificial softening of the first-year ZX-14’s bottom-end response in the lower gears.” This was also apparent while riding the bike in the pouring rain in Cambria, when trying to be smooth was occasionally thwarted by the slight restraint in throttle response. Our other minor gripe regards shift action between the six gears. Our test unit exhibited a notchy feeling, especially in our first couple hundred miles, but action did improve as we got more seat time. One area that offers zero hesitation is the chassis. Out goes the old steel frame and in its place is a stiff, diecast aluminum unit welded of five pieces. As with the company’s ZX-10R, main spars curve over the top of the engine to keep the bike slim between the rider’s knees.

Suspension front and rear is new. An inverted 41 mm Showa fork is now fully adjustable, with compression damping clickers added to the provisions for rebound damping and spring preload tweaks. The Showa shock and its linkage are mounted in a semi-horizontal position above the swingarm, where they help centralize mass and are protected from exhaust heat. The linkage ratio is identical to that of the previous bike’s Uni-Trak setup.

The new chassis and suspension package strikes an excellent balance between performance and comfort. “Chassis behavior on a winding road is very good,” said Hoyer. “Cornering response on turn-in is swift without being ultraquick, and steering effort is nicely weighted. There was a little wiggle at the apex on deep-lean corners, but this is often a byproduct of wide bars and unintended rider input. Otherwise, the Z1000 flicks in easily and settles into corners with a satisfyingly solid feel. Damping is on the taut side of comfortable, with good bump compliance. Despite the above-mentioned wiggle, the chassis feels rock-solid and substantial overall, very ‘together.’”

Chassis behavior also is almost unfailingly neutral, allowing the bike to be trail-braked deep into corners with no negative influence on steering input or control.

An area that typically gets ignored on Japanese nakeds is the brakes. Not so with the Zed. Up front is a top-line combination of an adjustable-span lever actuating a radial master cylinder and twin Tokico four-piston, radial-mount calipers that pinch 300mm petal discs. Feel and power from the front were excellent, with low lever effort and plenty of information from the contact patch at the limit. Canet commented after brake testing that the fork was well-damped and didn’t blow through the travel at first application, as is sometimes the case with standard-style bikes. Out back, the single-piston caliper and 250mm disc provided only adequate feel, making the rear tire too easy to accidentally lock up, especially in wet conditions.

Strictly speaking, the Z1000 isn’t a completely naked bike. There is the small upper fairing with projector-beam headlights and an aggressive lower cowl. In between, side fairings nicely incorporate turnsignals. Out back, the slim tailsection has clean lines while including hidden grabrails recessed into its underside. And then, of course, there is the white vinyl passenger seat of our Pearl Stardust White testbike (the orange accents get no billing in the official name)... Opting for Metallic Spark Black gets you a black passenger seat.

After hopping on the bike, the rider is met with a reasonable, 30.2-inch seat height, which allows firm footing for most riders of 5-foot-11 or taller. Reach to the solid-mount, motocross-style handlebar is natural and comfortable. The aluminum footpegs are a touch on the high side for a “standard” but offer excellent cornering clearance on this sportoriented bike. A small degree of engine vibration was noticeable through the aluminum pegs, but the plus side is that their knurled tops kept feet firmly-planted in all conditions, well worth any vibe-reducing comfort tradeoff provided by slippery-in-the-wet rubber strips. The seating position tilts the rider into a sporty but not overly aggressive pose without putting much, if any, weight on the wrists. Wind/rain protection is minimal, as you might expect, but the bikini fairing does take some air pressure off the rider’s chest. Mirrors are effectively-placed and offer a good rear view; the almost total absence of vibration through the handlebar helps keep things in focus.

With strong, real-world engine performance and no shortcuts taken on the chassis, the $10,499 Z1000 can punch out the daily commute or tear up a backroad with the best bikes in the class. This is not just another naked. O

EDITORS' NOTES

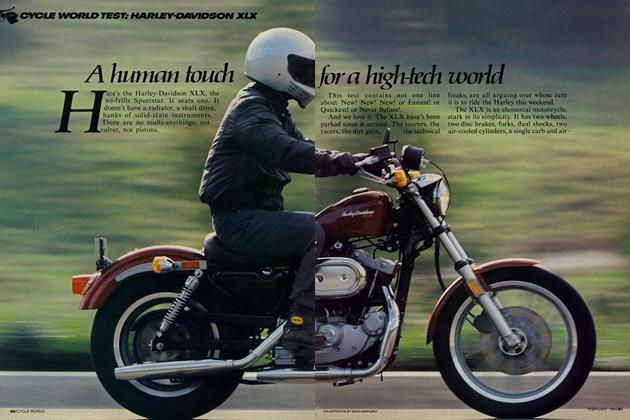

COME ON, PEOPLE, GET WITH THE PROgram! What is it about naked bikes that scares you? PR reps from every Japanese manufacturer have over the years repeatedly told me that feedback about these bikes is always positive, but when it comes time to cough up the cash, consumers run and hide.

I think I know the primary reason why: With the exception of a few European companies that “got it” from the get-go, other brands have struggled to recreate that raw, just-crashed-soi-put-MX-bars-on-it image combined with not-overdiluted, real-literbike engine performance. That’s what genuine streetfighters are all about. Instead, the Japanese usually gave us overly homogenized bikes with uninspiring styling, boring engines and cut-rate suspension, and thought wallets would flip open. But Kawasaki got it right this time: The Z1000 has balls! Lots of torquey power, excellent suspension, stand-it-on-the-nose brakes and sportbike-onsteroids styling. —Blake Conner, Associate Editor

I WAS THE STAFF MEMBER ASSIGNED THE task of looking after our long-term Z1000 test bike back when the original was introduced in 2003, so riding the latest version has been a trip down memory lane for me. It didn’t take more than a year or 10,000 miles in the saddle to recognize that this third-generation machine is worlds better than its predecessors in so many ways.

Topping my list are the huge reduction in vibration and improved seat comfort. Kawasaki has also upped the ante with performance and handling that puts the new Z on par with the nastiest production streetfighter-style machines.

Few bikes I’ve tested at the dragstrip get out of the hole as readily and easily as the Z, thanks to a nice blend of clutch feel, midrange torque and short gearing. Perhaps best of all, the Z1000 achieves this impressive level of performance without feeling too hard-core or narrowly focused. That’s a high standard worth retaining.—Do« Canet, Road Test Editor

HELLO, HONDA, IT’S ME AGAIN! HEY, I just got finished riding the wheels off this all-new Kawasaki Z1000. In between being impressed with the crisp turn-in response, abundant cornering clearance, comfortable riding position and the fully rock-’n’-roll-ready inlineFour, I kept having déjà vu. I felt like I’d ridden a really similar type of bike, but the brown SoCal scenery and the lack of cows standing in the road around the occasional blind corner weren’t quite right.

Then it all snapped into focus: The CB1000R I got to ride in the Alps (“Forbidden Fun,” CW, October, 2009)! Of course!

Must say Kawasaki has done an impressive job building an edgy-yet-well-balanced machine, one that has a very similar performance feel (if not quite the same refinement) as the CB1000R we don’t get here. Woulda been one hell of a comparison test! But you can’t win if you don’t play. Please tell me you’ll take a shot with the retro-air-cooler CB 1100? ! —Mark Hover, Editor-in-Chief

KAWASAKI Z1000

$10,499

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontKeeping Focus

MARCH 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

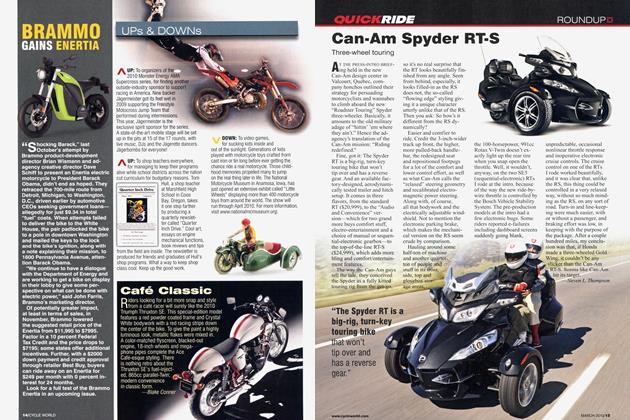

Roundup

RoundupAsphaltfighters Stormbringer: Autobahn Extraordinaire

MARCH 2010 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupEddie Lawson: 20 Years Later

MARCH 2010 By Nick Ienatsch -

Roundup

RoundupEtc...

MARCH 2010 -

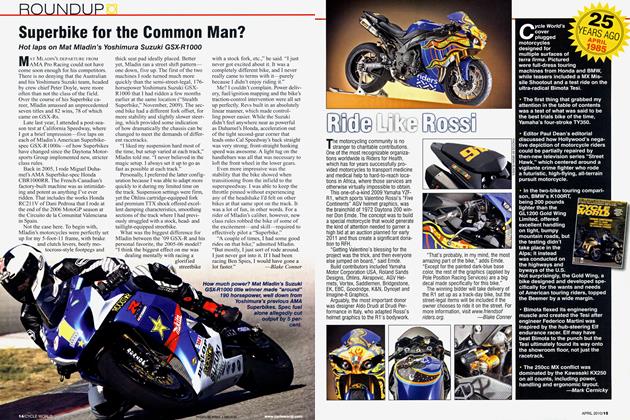

25 Years Ago March 1985

MARCH 2010 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupBrammo Gains Enertia

MARCH 2010