Seizing the Means of Production

UP FRONT

Mark Hoyer

HOVERING OVER THE BOTTOM HALF OF Yamaha RD350 engine cases, with razorblade in hand, I hear a seasoned, steady voice fill the space between me and its source, intoning itself around the lathe and mill, under the welder and between the teeth of the gearbox that was laid bare before me, oil shimmering on its parts. “If you put some lacquer thinner on a rag, that Yamabond will just wipe right off.”

I’d been scraping on the case joint for some time. Yamabond or ThreeBond had been in my sealant collection for a number of years, but never had I so easily removed it as I did chemically moments after the advice issued forth. It’s good to have help in this world.

The voice was Kevin Cameron’s, and he’s opened up more than a few RD cases over the years. Anyway, that these sealants could be thinned is something I should have known by then, but as it so often goes, the obvious things slip past us.

How could I have learned this chemical miracle sooner? What about all the other mechanical things I’ve learned the hard way over the years?

It’s a tough thing. I’ve had some good mentors, but there was never a time of the total package that combined my youthful enthusiasm and energy with the full experience of somebody who’d Seen It All and was willing to share it.

So I’ve picked up little pieces of information along the way and tried to build a deeper understanding of the mechanisms that move me.

For most of us, it is the enthusiasm for machines that leads the way; the need to fix them is merely an attendant side effect. The first motorized vehicles that made me appreciate the difference between things that ran and things that didn’t was a Tecumseh-powered go-kart I bought when I was 11 or so, then a pair of Batavus mopeds purchased for $50 when I was 14.

Out of necessity (lack of money), I had to work on these things myself and without much guidance, especially after my dad got bored with “adjusting the carb” on my go-kart, which really just meant I wanted to drive it around while he stood there watching with a screwdriver in his hand. I couldn’t ask Dad for help with the mopeds because they were a secret...

But I never had to rely on either of those machines for actual transportation, and they were more symbols of freedom than actual agents for it.

That’s what made my first real motorcycle—a 1979 Yamaha RD400 Daytona Special I bought when I was 16—so different. At the time, an RD400 was just a cheap used bike when I got it in ’85 or so, and it ran pretty well. But, after a while, the carbs went out of synch, the tires got worn, etc. Like a lot of people, I’ve always had a natural interest in how machines work, but certainly by the time I was 16, that drive to know came more from the simple desire to ride. If I didn’t fix my bike, I didn’t get to go where I wanted, feel the freedom of kickstarting my RD and listening to the Tommy Crawford chambers make their wonderful note on the road behind me (they sounded much better than the Stockers, especially after one of the baffles blew out on the road).

In fact, I learned something from Mr. Crawford when I picked up my bike at his shop after he installed the pipes: “You might want to look at the rear wheel alignment—I could feel the bike crabbing when I test rode it.”

The best you know is the best you’ve tried, and since “crooked” was all I knew of streetbikes at the time, I thought it was normal. But TC’s little remark was a first step in expanding my understanding.

The job was relatively simple and the benefits were clearly detectible. Sweet! I felt powerful to have a positive influence on my motorcycle. That incident helped trigger the idea that there was more to it all than just whether it ran or not. It opened the door to the idea of ongoing improvement. It also taught me to listen to people.

Not all projects turn out positive at first whack, though. In fact, there have been a lot of fix-it disasters, and I can think of many occasions where it would have been cheaper to have paid somebody to do the job than for me to make worse what I was trying to fix. My first car engine rebuild, for example, ended with a broken camshaft on startup. I put a tiny little thrust washer in the wrong place and bound up the distributor drive gear.

That’s a crushing blow, the kind of thing that could make you quit, make you think it’s just better to turn it all over to somebody else.

But any sane person buys more tools and then seeks help. Which is what had taken me to Kevin’s shop with my RD350.1 was capable of doing a straight rebuild on this old beater, but I wanted to get more from this machine and to learn more about the finer points. I also wanted to ask Kevin how he had learned so much, envisioning stories of grand apprenticeships in which wisdom of elders was passed on in a thoughtful, orderly and educational manner.

But like almost every accomplished mechanic/tuner I’ve ever sought advice from, Kevin’s response was simple: The scope of understanding and expansiveness of view comes from standing on top of a mountain of broken parts. But he added that, over the years, he’d learned to listen to people and make note of those important nuggets that sometimes come from unexpected sources during off-handed comments. Like the exhaust pipe guy who taught me my first thing about chassis alignment.

So while I had lamented my own lack of studied guidance, he’d really gone about the whole thing in a similar way but had just taken it much, much farther.

I’ve gotten a lot better at fixing things over the years and expanded my tool collection to include those for metal shaping, welding, milling, wiring and more. And the freedom I feel when running the TIG welder or attempting to fabricate a custom fender is just as great as that I get from riding a motorcycle I restored or repaired and rode without breakdown.

But even now, it’s good to have a fellow looking over your shoulder and telling you to put down the razorblade. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Roundup

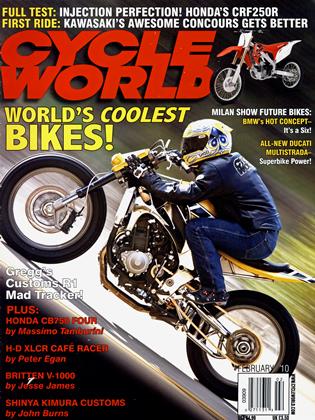

RoundupSexysix

FEBRUARY 2010 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

RoundupKiller Concepts

FEBRUARY 2010 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

Roundup2010 Mv Agusta F4

FEBRUARY 2010 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

RoundupKtm Concept 125 Supermoto Racers

FEBRUARY 2010 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

RoundupBetter Boxers

FEBRUARY 2010 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

RoundupEtc...

FEBRUARY 2010