Tool Time

There is no doubt it all started with a rock. But the hammer, and our ability to whack things, has come a long way.

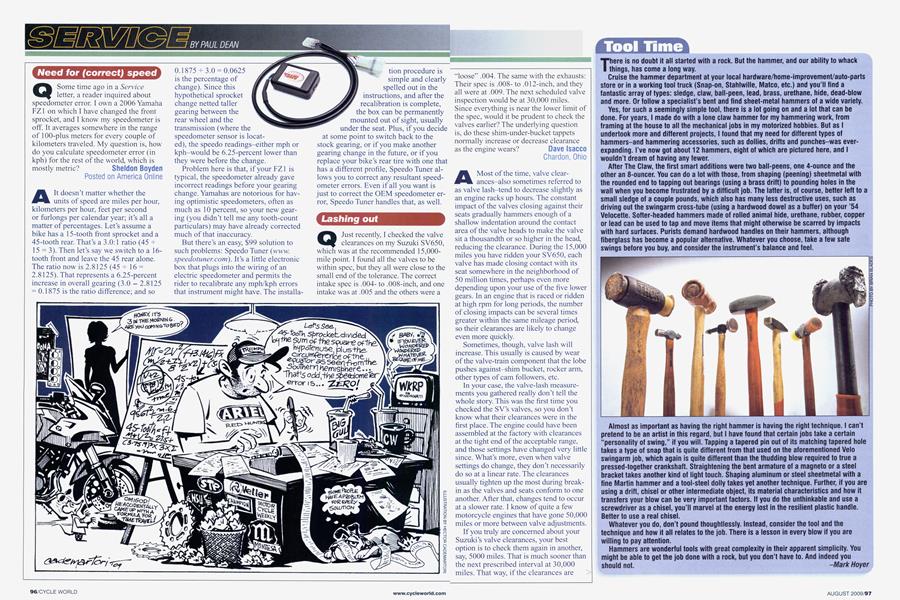

Cruise the hammer department at your local hardware/home-improvement/auto-parts store or in a working tool truck (Snap-on, Stahlwille, Matco, etc.) and you’ll find a fantastic array of types: sledge, claw, ball-peen, lead, brass, urethane, hide, dead-blow and more. Or follow a specialist’s bent and find sheet-metal hammers of a wide variety.

Yes, for such a seemingly simple tool, there is a lot going on and a lot that can be done. For years, I made do with a lone claw hammer for my hammering work, from framing at the house to all the mechanical jobs in my motorized hobbies. But as I undertook more and different projects, I found that my need for different types of hammers-and hammering accessories, such as dollies, drifts and punches-was everexpanding. I’ve now got about 12 hammers, eight of which are pictured here, and I wouldn’t dream of having any fewer.

After The Claw, the first smart additions were two ball-peens, one 4-ounce and the other an 8-ouncer. You can do a lot with those, from shaping (peening) sheetmetal with the rounded end to tapping out bearings (using a brass drift) to pounding holes in the wall when you become frustrated by a difficult job. The latter is, of course, better left to a small sledge of a couple pounds, which also has many less destructive uses, such as driving out the swingarm cross-tube (using a hardwood dowel as a buffer) on your ’54 Velocette. Softer-headed hammers made of rolled animal hide, urethane, rubber, copper or lead can be used to tap and move items that might otherwise be scarred by impacts with hard surfaces. Purists demand hardwood handles on their hammers, although fiberglass has become a popular alternative. Whatever you choose, take a few safe swings before you buy, and consider the instrument’s balance and feel.

Almost as important as having the right hammer is having the right technique. I can’t pretend to be an artist in this regard, but I have found that certain jobs take a certain “personality of swing,” if you will. Tapping a tapered pin out of its matching tapered hole takes a type of snap that is quite different from that used on the aforementioned Velo swingarm job, which again is quite different than the thudding blow required to true a pressed-together crankshaft. Straightening the bent armature of a magneto or a steel bracket takes another kind of light touch. Shaping aluminum or steel sheetmetal with a fine Martin hammer and a tool-steel dolly takes yet another technique. Further, if you are using a drift, chisel or other intermediate object, its material characteristics and how it transfers your blow can be very important factors. If you do the unthinkable and use a screwdriver as a chisel, you’ll marvel at the energy lost in the resilient plastic handle. Better to use a real chisel.

Whatever you do, don’t pound thoughtlessly. Instead, consider the tool and the technique and how it all relates to the job. There is a lesson in every blow if you are willing to pay attention.

Hammers are wonderful tools with great complexity in their apparent simplicity. You might be able to get the job done with a rock, but you don’t have to. And indeed you should not. -Mark Hoyer

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

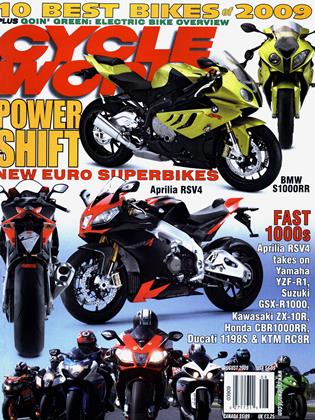

Up FrontTen Rest, 2009

August 2009 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Guy of the Moment

August 2009 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCInstruments of Control

August 2009 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

August 2009 -

Roundup

RoundupElectric Arrival

August 2009 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago August 1984

August 2009 By Paul Dean