BIG BASE

RACE WATCH

A father-son reunion on the Daytona sand

DON EMDE

DAYTONA BIKE WEEK 2008 HAD SPECIAL SIGNIFICANCE FOR ME and my family. It was the 60th anniversary of the ’48 Daytona 200 win by my father, Floyd Emde. In the fall of 2006, I’d already been thinking about that upcoming anniversary when a bike listed for sale in Jerry Wood’s Vintage Motorcycle Auction catalog caught my attention. It was a rare Indian 648 Big Base Scout, the same model that Floyd had ridden to victory. I couldn’t imagine a better way to celebrate the anniversary than to build an accurate replica of his winning Big Base Scout and take it to the 2008 Bike Week.

But before I get into how the Indian 648 “Floyd Emde Replica” actually came together, some background information.

World War II had not been good financially for the Indian Motocycle Company. Poorly negotiated contracts with the government resulted in Indian coming out of the war years badly wounded from its participation in military motorcycle production.

Believing that publicity from a Daytona 200 victory would give the brand a needed shot in the arm, Indian management decided to launch an all-out assault on the 1948 Daytona 200.

They decided to build a special batch of 50 production racebikes for Daytona, dubbed “Model 648.” Indian’s budget was very limited but the concept was sound. The machine would put the most powerful 45-cubic-inch (750cc) Sport Scout motor Indian knew how to build into a chassis that would not only handle well on the demanding 4.1-mile beach course but also provide the durability to finish the 200-mile distance. The beefed-up rear frame section and other parts off the Model 741 Military Scout

were utilized for that purpose. And for additional reliability, the engine featured an extra oil chamber in the crankcase, which is where the nickname “Big Base” came from.

According to Indian historians, the plan to produce 50 motorcycles resulted in something closer to only 25 or so complete bikes built for 1948, with a few additional engines and spare parts made in the years to follow.

Floyd Emde, who passed away in 1994, was one of America’s

top motorcycle racers of the post-war period. In 1946, he won the California State TT Championship among many race victories and track records he set that year. These were followed by numerous wins in 1947, including a victory at the 10-mile National Championship race at Milwaukee-all aboard Harley-Davidsons.

His plans to race a Harley WR in the ’48 Daytona 200 changed a few months before the race when sponsor Bill Ruhle, the Harley-Davidson dealer in San Diego, died of a heart attack. It was not long, however, before Guy Urquhart, the competing Indian dealer in town, heard of Floyd’s situation and offered to sponsor him on one of the new 648 Big Bases. Emde jumped at the opportunity.

When growing up in San Diego, Floyd was in the Boy Scouts, and their “Be Prepared” motto stuck with him throughout his life. He always had the ability to think ahead and would ask “what if’ kinds of questions about

potential problems.

He was also a good mechanic, having worked as a flight engineer at Consolidated Aircraft in San Diego (formerly Ryan Aviation, where Charles Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis was built). During the war, Floyd did in-flight final-inspection runs on B-24 bombers built there. So mechanically, when he saw a problem, he was trained to do something about it.

The Indian 648 arrived from the factory in Massachusetts only a few weeks before Floyd needed to leave for Daytona. Time was short, but he and his mechanic, Noel McIntyre, took the bike out for a ride to break in the motor. They also made numerous changes to solve potential problems they spotted.

Key modifications included replacing the large floorboard with a footpeg on the left side so it would not catch in the deep, sandy ruts in Daytona’s turns (all left-handers). He also swapped the stock Indian air-cleaner to an automotive-style filter that provided a better seal around the carburetor and a rear-facing inlet to keep out sand and salt water.

Something that Floyd addressed better than anyone in the event was the riding position for the long, two-mile straightaways. He added a Harley WR pillion pad on the rear fender to allow him to scoot back and get fully tucked in. And to make the >

riding position comfortable, he added buddy pegs so his legs could stretch out as he leaned forward with his chest on the toolbag strapped to the gas tank. The bracket that held the toolbag also served as a place to paint numbers, a code he had for pit signals received during the race.

One other modification shows best how well Floyd had thought through every possible problem that might prevent him from finishing. The pits were

at the far southern end of the beach, two interminable miles from Tum 1. So, in case he ran out of gas near that first turn, he strapped a quart can to the frame filled with enough fuel to get him back to the pits. He didn’t actually have to use it in the race but it was there if he had needed it.

In 1948, the race was started one row at a time in 6-second intervals, and the riders’ elapsed times were used for scoring the final results. They drew for starting position back in those days, and a good draw was important. Any-

one with an AMA Expert license could race in the 200; so with 153 entries, everyone knew the two sandy turns on the beach course would get tom up quickly.

A sign that this was Floyd’s year came when he drew a front-row starting spot. At the flag, he jumped into the lead and led all the way to the finish; at one point, he led second-place rider Billy Mathews by more than a minute. After receiving the “OK” signal from the pits about midway through the race, Floyd went into cruise mode and still beat the Canadian Norton rider by 18 seconds.

Although Indian riders Ernie Beckman, Bobby Hill and Bill Turnan would log dirt-track victories for a few more years, Floyd’s 1948 victory was the last-ever at Daytona for Indian. In the years to come, the three-speed, handshift Scout gave way to improving British racebikes as well as the all-new four-speed Harley-Davidson KR. And in 1953, the Indian factory in Springfield closed its doors for good.

The original Indian 648 that my father raced does still exist. It is in the collection of John Parham, on display at Parham’s J&P store at Destination Daytona in Florida. For my purposes, >

however, I needed a machine always available for displays and exhibits, plus I wanted it set up exactly as raced by my father in 1948.

Something I was not lacking was a large supply of photos and magazines showing Floyd and the bike. It was fun doing the research to figure out exactly how the numberplates were painted, what grips were on the bike, how he had a made an ignition kill button out of a hacksaw blade, and more. The goal was to get all the parts as exact to that bike’s 1948 specification as we could make them.

Crucial to the end result was to hire the right person to do the restoration work. My first call went to Steve Huntzinger, someone I have known for a long time and whose work is second to none. Through the years, he has created some absolutely fantastic restorations.

He quickly accepted my challenge.

I was able to obtain the Indian at Wood’s auction, but about the time the preliminary arrangements were coming together to get the restoration started, a lucky star shined on me: A second Big Base Scout came up for sale in another auction in Kansas City. How great was that? No more than 25 complete 648s were known to have ever been built, and within months of each other, two were for sale! I got on a plane and went to K.C. determined to place the winning the bid on this Indian, too, which thankfully I did. Parts for a 648 are very hard to find, and now I had two machines to work from to build one accurate bike.

Huntzinger soon had both bikes in his garage and work began. When it came to the final details, some additional help and resources were called in. One of the bikes came with the correct Firestone ANS rear tires as used by Floyd in 1948, but we needed an even-more-rare Firestone rib front tire. As luck would have it, on a visit to Dale Walksler’s Wheels Through Time Museum in Maggie Valley, North Carolina, I mentioned my need. Within minutes we were up in Dale’s parts loft, and soon I was holding the very tire I needed. Problem solved!

Indian-script tank decals are easy to find; not so for the correct Indian dealer decal for the rear fender or the Wynn’s Friction Proofing decals for the oil tank. After searching on eBay, I found similar decals that allowed us to make the needed artwork, and I had original-style water transfers made up.

The last big hurdle was figuring out what to do about the toolbag. I called >

Tom Seymour at Saddlemen, who, in addition to being a manufacturer of leather products, is a longtime motorcyclist who I knew would buy into the project. He came through wonderfully and created a very cool 1940’s-looking bag that is as close to the original as we could get.

Things couldn’t have gone more perfectly at Daytona. On the Monday and Tuesday of Bike Week, I was invited to ride the Big Base in AHRMA’s “Great Men & Machines” vintage bike parade around the International Speedway. That was great, to be sure, but the highlight of the week was on Wednesday when I had the bike on the beach for the inaugural Daytona 200 Monument party. Monument creator Dick Klamfoth, himself a three-time Daytona 200 winner, graciously allowed us to use the Emde Replica as the theme bike for the event.

So, when it was all said and done, I had achieved my goal. We had a running Indian 648 Big Base Scout back on the famed sand at Daytona, set up exactly as my father had ridden it that March day in 1948 when he raced into the history books.

it was a little eerie, to be honest. I wasn’t even bom when he won the race, yet I was having a déjà-vu moment. □

Don Emde is also a Daytona 200 winner, riding to victory on a Yamaha TR2 in 1972, making the Erndes the only father and son to have done so. Don is the president of Don Emde Publications and author o f The Daytona 200: The History of America’s Premier Motorcycle Race. An updated third edition is in the works.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

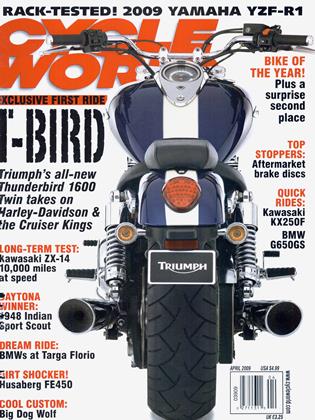

Up FrontBike of the Year

April 2009 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Captive Enfield

April 2009 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCBreakage

April 2009 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

April 2009 -

Roundup

RoundupCall of the Wild

April 2009 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupCustoms Live: Reports of Hot-Rodding's Demise Have Been Greatly Exaggerated

April 2009 By Paul Dean