Art and the Motorcycle Museum

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

NOVELIST KURT VONNEGUT ONCE WROTE that his sister, who was a professional artist, never understood how anyone could spend hours in an art museum, sitting on a bench and staring quietly at a famous painting. She claimed she could race through a museum on roller skates, give each painting a quick look, say, “Got it!” and then skate on to the next room. She thought a great painting either hit you with that magical flash of insight or it didn’t.

I think we can all see the problem here: She was skating through a museum full of paintings rather than motorcycles.

I know this because I just spent a couple of back-to-back weekends visiting two famous motorcycle museums, and I never had the slightest desire for a pair of roller skates.

What I needed was a large collection of strategically placed La-Z-Boys. The kind with drink holders built into the arms. But then I can spend three hours just staring at the right side of a BSA Gold Star, so I may not be the typical art critic.

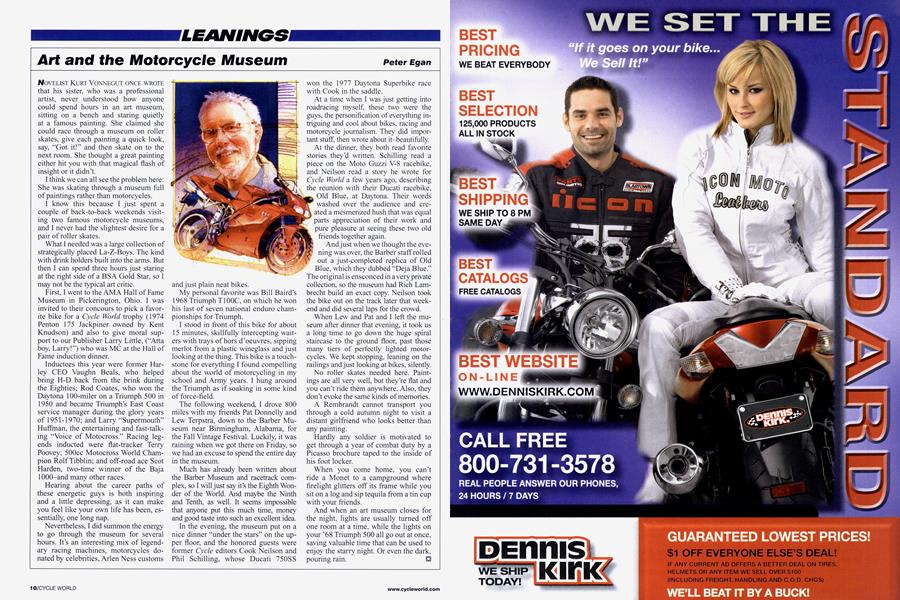

First, I went to the AMA Hall of Fame Museum in Pickerington, Ohio. I was invited to their concours to pick a favorite bike for a Cycle World trophy (1974 Penton 175 Jackpiner owned by Kent Knudson) and also to give moral support to our Publisher Larry Little, (“Atta boy, Larry!”) who was MC at the Hall of Fame induction dinner.

Inductees this year were former Harley CEO Vaughn Beals, who helped bring H-D back from the brink during the Eighties; Rod Coates, who won the Daytona 100-miler on a Triumph 500 in 1950 and became Triumph’s East Coast service manager during the glory years of 1951-1970; and Larry “Supermouth” Huffman, the entertaining and fast-talking “Voice of Motocross.” Racing legends inducted were flat-tracker Terry Poovey; 500cc Motocross World Champion Rolf Tibblin; and off-road ace Scot Harden, two-time winner of the Baja 1000-and many other races.

Hearing about the career paths of these energetic guys is both inspiring and a little depressing, as it can make you feel like your own life has been, essentially, one long nap.

Nevertheless, I did summon the energy to go through the museum for several hours. It’s an interesting mix of legendary racing machines, motorcycles donated by celebrities, Arlen Ness customs and just plain neat bikes.

My personal favorite was Bill Baird’s 1968 Triumph T100C, on which he won his last of seven national enduro championships for Triumph.

I stood in front of this bike for about 15 minutes, skillfully intercepting waiters with trays of hors d’oeuvres, sipping merlot from a plastic wineglass and just looking at the thing. This bike is a touchstone for everything I found compelling about the world of motorcycling in my school and Army years. I hung around the Triumph as if soaking in some kind of force-field.

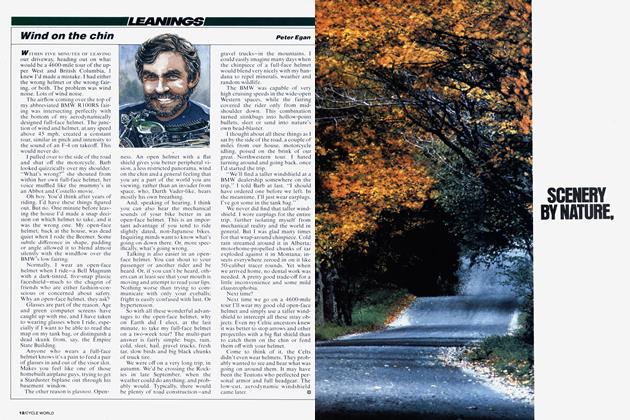

The following weekend, I drove 800 miles with my friends Pat Donnelly and Lew Terpstra, down to the Barber Museum near Birmingham, Alabama, for the Fall Vintage Festival. Luckily, it was raining when we got there on Friday, so we had an excuse to spend the entire day in the museum.

Much has already been written about the Barber Museum and racetrack complex, so I will just say it’s the Eighth Wonder of the World. And maybe the Ninth and Tenth, as well. It seems impossible that anyone put this much time, money and good taste into such an excellent idea.

In the evening, the museum put on a nice dinner “under the stars” on the upper floor, and the honored guests were former Cycle editors Cook Neilson and Phil Schilling, whose Ducati 750SS won the 1977 Daytona Superbike race with Cook in the saddle.

At a time when I was just getting into roadracing myself, these two were the guys, the personification of everything intriguing and cool about bikes, racing and motorcycle journalism. They did important stuff, then wrote about it-beautifully.

At the dinner, they both read favorite stories they’d written. Schilling read a piece on the Moto Guzzi V-8 racebike, and Neilson read a story he wrote for Cycle World a few years ago, describing the reunion with their Ducati racebike, Old Blue, at Daytona. Their words washed over the audience and created a mesmerized hush that was equal parts appreciation of their work and pure pleasure at seeing these two old friends together again.

And just when we thought the evening was over, the Barber staff rolled out a just-completed replica of Old Blue, which they dubbed “Deja Blue.” The original is ensconced in a very private collection, so the museum had Rich Lambrecht build an exact copy. Neilson took the bike out on the track later that weekend and did several laps for the crowd.

When Lew and Pat and I left the museum after dinner that evening, it took us a long time to go down the huge spiral staircase to the ground floor, past those many tiers of perfectly lighted motorcycles. We kept stopping, leaning on the railings and just looking at bikes, silently.

No roller skates needed here. Paintings are all very well, but they’re flat and you can’t ride them anywhere. Also, they don’t evoke the same kinds of memories.

A Rembrandt cannot transport you through a cold autumn night to visit a distant girlfriend who looks better than any painting.

Hardly any soldier is motivated to get through a year of combat duty by a Picasso brochure taped to the inside of his foot locker.

When you come home, you can’t ride a Monet to a campground where firelight glitters off its frame while you sit on a log and sip tequila from a tin cup with your friends.

And when an art museum closes for the night, lights are usually turned off one room at a time, while the lights on your ’68 Triumph 500 all go out at once, saving valuable time that can be used to enjoy the starry night. Or even the dark, pouring rain.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue