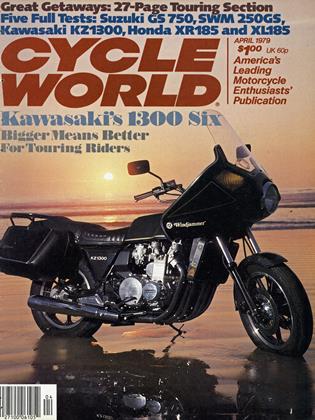

The French Quarter Connection

A Sense of Adventure, a Honda 400 and a Search for Cheap Chicory Coffee

Peter Egan

I stared at the top of the coffee can in disbelief. "Five sixty-nine for a pound of Louisiana French Roast Coffee? That's ridiculous!" I exclaimed to my wife, who agreed. "Three months ago it was two ninety-five." I couldn't believe it. My favorite blend of chicory coffee—which everyone tells me tastes like kerosene—had nearly doubled in price. I put the can back on the shelf. “I won’t pay it!” I said, loudly enough to be overheard by the assistant manager of the supermarket, who was hovering nearby with a clipboard and a matching shirt and tie. “In fact,” I added, “I think I’ll run down to New Orleans to buy my coffee.”

continued on page 112

continued from page 107

It was a pretty flimsy excuse for a 3000 mile motorcycle odyssey that would take me the full length of the Mississippi, all the way to the Gulf and back to Wisconsin, but it was just what I was looking for.

Ever since I was a kid I’d wanted to take a raft trip down the Mississippi; maybe start in Minnesota near the headwaters and drift down to New Orleans, watching the famous old river towns and the green shoreline slip past while I sat back on a pile of provisions and smoked a pipe.

Then one summer I worked on a Burlington Railroad section crew along the Mississippi and I saw the river in action. Whole oak trees floated by, only to disappear in sudden, mysterious undercurrents; hydroelectric towers and dams swallowed millions of gallons of water from greenish whirlpools of their own making; and tugs pushed half a mile of unwieldy barges around blind river bends. It was all a far cry from Huck Finn’s sleepy river, and no place for a novice—especially a novice with an unnatural fear of Indifferent Nature, as manifested in the force of fast-moving water.

It suddenly dawned on me that a motorcycle trip down the Great River Road might be a pleasant, relatively non-lethal, alternative to rafting. I could still visit those famous cities and towns and keep an eye on the river itself. “And,” I asked myself, “what Twentieth Century vehicle lives more in the spirit of Huck Finn’s raft than a motorcycle?”

“Why, none,” I answered.

The prospect of a river trip, together with a chance to score a can of cheap French Roast coffee was too much. I opened the attic closet and got out My Things.

My Things, it turned out, were all wrong for the trip. I realized that nearly all of my cycle gear is intended for cold or cool weather riding, which is the rule rather than the exception in Wisconsin. Since I was heading south in the middle of August, I would have to leave it all behind; my leather jacket, my Belstaff suit, gauntlet-style gloves, down bag, and riding boots. It was strictly tennis shoe and Tshirt weather. I took a denim jacket for early morning and late evening riding, an old Army blanket to sleep on rather than in, half a gallon of Cutter’s mosquito repellent, and Big Pink—a faded red pup tent from childhood, so shopworn that I can gaze at stars through the fabric at night.

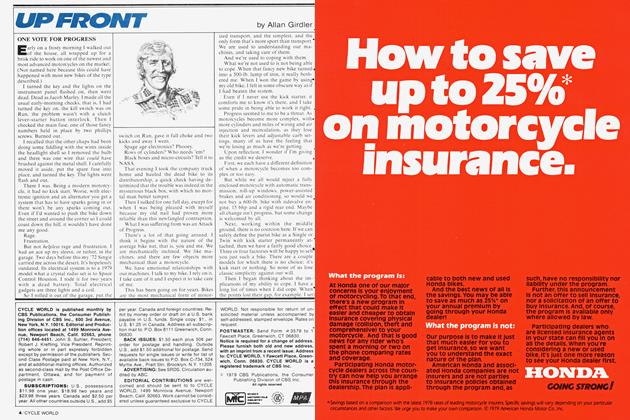

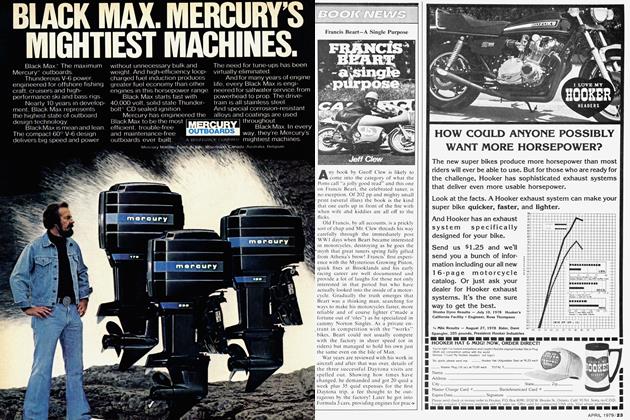

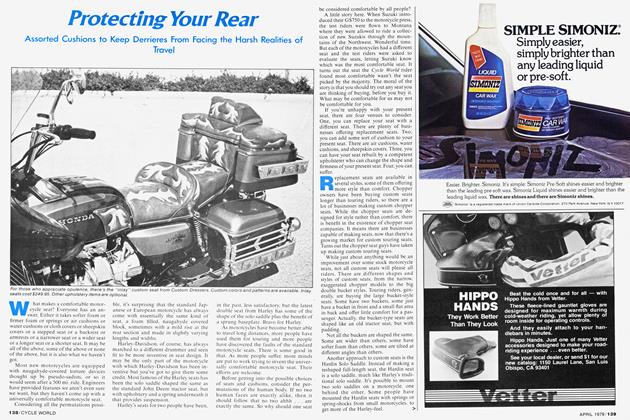

The motorcycle would be my latest pride and joy, a 1975 fire-engine red Honda 400F Super Sport. There are those who would (and several who did) point out that the 400F is a rather precise instrument to use in the bludgeoning of 3000 miles of open highway; a waste, in effect, of a machine whose forte is 410 Production racing or the Sunday morning ride on twisty blacktop. They are right, of course. It was for that kind of sport that I bought the bike. Even as it sat in my garage, the 400 was on the brink of being converted into a 410 Production racer. All of the racing parts were laid out in neat array on my workbench. I had a set of Konis, some flashy orange S&W 70-110 progressive springs, two new K-81s, three plastic number panels, a set of Racer-1 clubman bars, four quarts of Castrol G.P. 50-weight, and a roll of safety w ire. But my first race was five weeks away, and I was up for a good road trip.

And, purist considerations aside, the 400 does make a fine road bike. It is utterly reliable, handles legal and extra-legal highway speeds easily, is not awkward to maneuver in tight places (no embarrassing assumption of the beached w hale position while a whole campground looks on), and it looks and sounds good. Also, I prefer the short, straight bars so I can lean into the wind while I ride, as opposed to the more popular dumping-a-wheelbarrow-full-ofconcrete riding style. With a light luggage load—I took only an Eclipse tank bag and a duffel bag on the rear seat—the bike handles almost as well as the unladen item, and makes riding on curving roads a genuine pleasure. Nothing is more annoying than to be stuck with half a ton of mechanical corpulence when the riding gets fun.

At seven o’clock on a Friday morning I kissed my wife good-bye, patted our three cats on the head, and rode off into a hot and gloriously sunny morning. Just outside of town I stopped to install some ear plugs I’d bought to ward off total deafness on the long trip. After five minutes, I had to stop and take them out. They worked too well; I couldn’t hear a thing. They made riding surreal, and eerily quiet. For all I knew, my exhaust header had fallen off and a broken rod was hammering my block to pieces. I began to fantasize engine and chassis noises, much the way someone wearing stereo headphones constantly imagines that the phone and doorbell are ringing. Like those early airline pilots who objected to enclosed cockpits, I preferred to hear the wind in the wires and ignore the instruments.

The first leg of my trip did not take me south toward New Orleans, but 500 mi. north to the Minnesota resort town of Brainerd. I wanted to make a proper river trip out of it, and start near the headwaters of the Mississippi. The true source of the river is Lake Itasca, northwest of Brainerd, from which the river flows in none-tooimpressive volume through Bemidji and southward through many small lakes, gathering strength. I went to Brainerd because I have good friends, Tom and Lynn Dettman, who have a farm and cabin near the town. I also wanted to scout around Brainerd International Raceway for an upcoming road race—and another chance to unleash Lola the Vicious Underdog, my battlescarred and outdated Formula Ford racing car. (Lively, these little towns in the North Woods.)

I rode into Brainerd after 10 hours on the bike and after dark, equipped with a copy of a copy of a hand-drawn map purporting to show the way to Dettman’s cabin, some 20 mi. from town. Three hours later, on a mosquito-clouded back road in the dark forest, I gave up searching for the imaginary landmarks on my map, switched my tank to reserve, and prayed I’d make it back to town. I rolled into a gas station and cafe in Brainerd at one in the morning, my engine sputtering.

“Is there anyplace around here I can lie down and sleep?” I asked the waitress over a cup of coffee in the restaurant. “I must have sleep. I’ve been on my motorcycle for thirteen hours.”

“There’s some old railroad cars down by the river. You could sleep in those,” she offered.

“Perfect,” I said. As I left the cafe, the cook at the grill shouted, “You bed dowm in one of them railroad cars and you just might wake up in North Dakota!” She cackled and flipped a hamburger. I didn’t care. I had to lie down.

In the morning I awoke on a bench in a vandalized caboose car and found myself lying in a bed of cigarette butts, crushed Dixie Cups, and spent lime vodka bottles; all features I’d overlooked while stumbling in from the night fog. I brushed myself off and looked out the train window. I was still in Minnesota—or what the mosquitos had left of me was still in Minnesota. The mosquitos in that state are so large that they lack the usual high-pitched w'hine, and drum their wings at a much lower frequency, like quail taking off from a thicket.

With the aid of sunlight and friendly natives I managed to find Dettman’s place, a remote cabin on a beautiful little lake, which they share only with a Bible camp. Tom showed me around the town and the race track. We spent the evening visiting, and my second night on the road, sleeping in their cabin on the lake, was considerably more pleasant than the first—though Tom persisted in addressing me as “Boxcar Egan”. They fixed me a good breakfast for a sendoff down the river.

South of Brainerd the Mississippi develops into a solid, respectable little river that winds easily through flat Minnesota farm land, widening here and there to water the marshlands of wild rice and cattails. It passes through Little Falls, where Charles Lindbergh lived before he had the good sense to move to Madison, Wisconsin— where he attended the University before he had the good sense to quit school and take up flying. South of St. Cloud, the river gets lost in the fast-growing suburbs and the downtown(s) of the Twin Cities. The Falls of St. Anthony, once a landmark and barrier to upper river navigation, are nowcaught between two dams and circumvented by a lock system. Modern cities have a way of overwhelming the physical features that once determined their locations, until those features are lost and unimportant. I spent part of my youth in St. Paul and never heard anyone mention the Falls, nor did I ever see them.

At Prescott, Wisconsin, the St. Croix River joins its crystal clear waters to the already Muddy, if not very Big, Mississippi. I decided to follow Highway 61 down the Minnesota side, having seen too much of the Wisconsin side when I worked on the railroad and literally shoveled my way from Prescott to Bluff Siding.

Highway 61, from Hastings to LaCrosse, Wisconsin, is one of the nicest cycle rides on the Mississippi; four lanes, smooth and uncrowded, undulate along the river bank high enough to afford a constant panorama of the river and its islands. I discovered at this stage of the ride that every gas station, no matter where you go, employs one high school student who either owns or is about to own a motorcycle, and can discuss motorcycles with incredible expertise, usually quoting cycle magazines verbatim. A station attendant in Red Wing told me that my 400F had “an engine that lives just to bury the tach needle.” I nodded my agreement, suppressing a shiver of déjà vu and wondering where I’d read those words.

At LaCrosse I shifted to the more scenic Wisconsin river bank and cruised through a dozen small river towns until I reached Wyalusing State Park. The park sits high on the bluffs at the junction of the Wisconsin and Mississippi, and offers a splendid view of both rivers. I erected Big Pink near the campsite of a young couple who had a trailer and two curious children. The father seemed determined that the kids stay clear of me and my motorcycle and shouted at them roughly whenever they ventured too close. Feeling rather untouchable (perhaps it was the dead insects pasted to my chin), I sat alone on the bluffs, watching a huge red sun set over Iowa and sipping a little Cabin Still from a brown paper bag I’d brought along.

The day was already calm and breathlessly hot at seven in the morning when I broke camp and rode down to Galena, Illinois for breakfast. Galena was a prosperous old river town that fell upon hard times and was nearly abandoned, until a later generation recognized the value and charm of the beautiful old homes and shops in the city. Galena is now a tourist attraction, with hundreds of nicely restored buildings and a remarkable collection of brick storefronts along its main street. It is a town that must have the highest ratio of antique shops to population in the entire country. On the edge of town I visited the home of U.S. Grant, which is filled with photographs of the General and his family. Grant always looking a bit rough-hewn and out-of-place amid the lavish parlor trappings of that era. In my own heatdistorted mind I began to pity the people in the photographs for their lack of shorts and sandals, because it was about 100° in Grant’s house. It was good to get back on the Honda.

In Fulton, Illinois, farther down the river, I sat at a lunch counter with two young men who told me that St. Louis was a tough town, and I should steer around it. “You go through St. Louis on that shiny red motorcycle and, sure as hell, someone’ll drag you right off that bike and take all your stuff away. I heard about it.” His friend concurred grimly, then ordered a turkey sandwich with gravy. As he ate the sandwich, he leaned over to his buddy and said, “Bird Dog can eat six of these.”

“Hail.”

“I seen ’im.”

I walked out into the street, keeping a sharp eye out for the legendary Bird Dog and wondering if I dared go through St. Louis on my shiny red bike. I tossed caution to the wind and headed south.

I followed the Great River Road (always marked with a green sign that bears a giant steamboat wheel) and cruised through the Moline and Rock Island half of the Quad Cities-factory towns that are incredibly clean and modern looking for a traditional industrial area. The John Deere plant is so gleaming and up-to-date it looks almost Japanese.

Just north of Nauvoo, Illinois, I ran across another touring motorcyclist. At a four-way stop in the middle of nowhere we got off our bikes to have a cigarette and talk. He was Roy Perkins, from Roanoke, Virginia, and he was touring on a Kawasaki 400 triple. “I wouldn’t ride anything but a Kawasaki two-stroke,” he told me. “I’ve never had a lick of trouble with ’em. And I wouldn’t ride anything bigger than a 400—you don’t need any more than that.” Roy was traveling even lighter than I was; he had nothing but a backrest with a pack strapped to it and a tent roll across his rear seat. “I’m going to Seattle, down to Mexico, then back home around the Gulf coast and Florida,” he said. “The main thing I like to see is Indian mounds. I’ve seen every Indian mound between here and Virginia, and I plan to see them all along my trip.” I thought of Kawasaki’s “We know why you ride” advertising slogan. and I wondered if they knew about Roy Perkins and his Indian mounds. Before we parted, he warned me to stay out of Mississippi. I asked why. He kick-started his bike and lifted his face shield for a moment. “Trouble,” he said. He flipped his shield down and rode away, waving.

Before sundown I was in Nauvoo State park, staking down my tent. As soon as my cycle stopped moving, I realized that the only factor preventing me from melting into a smouldering shapeless lump of steaming flesh was the air that moved past me and the Honda all day. By the time my tent was in place I was a sweaty wreck, so I rode into town and had five beers for dinner at an air-conditioned bar, where I watched an entire Pirates vs. Reds baseball game on TV, even though I hate baseball. When the bar closed, I was forced back to my tent for a long night of involuntary weight loss.

In the morning I toured Historic Nauvoo, the last home of the Mormons before they were forced by persecution to move west to Utah, led by Brigham Young. A Mormon restoration corporation is buying up and rebuilding the old brick settlement, and the restoration they have already done is first class. Four acres surround each home and shop in an idyllic setting whose beauty imparts some of the sorrow' those settlers must have felt in leaving what they’d built. Before I left town, I bought a bottle of Old Nauvoo Brand Burgundy Wine, a modern legacy of the French Icarians who moved in to plant vineyards when the Mormons left. (The wine was excellent when I got home, even after five days in my tank bag; truly a Burgundy that travels well.)

At Keokuk, I paid 30 cents to cross the Mississippi on a steel-mesh bridge—the kind of surface that sends motorcycle tires into a frenzy of squirming indecision—and was greeted by a sign that said “Welcome to Keokuk, Iowa. Sailors have more fun!” (Okay, sure. But in Keokuk. Iowa?) I turned south on 61 toward Hannibal, Missouri, home of Mark Twain.

In Tom Sawyer, Twain described his home town as a “poor little shabby village.” It’s not so little any more, but the river town that surrounds the block of old houses claiming to be Tom Sawyer’s neighborhood has taken on a modern shabbiness to disillusion romantics and young readers. A giant rotating fried chicken barrel looms just beyond Tom’s house, and trucks rumble across the busy highway bridge behind it. A few blocks away, a scrap metal yard lines the river bank. There are many small towns, up and dowm the river, much closer in spirit and form to the village Twain immortalized than Hannibal is today.

I had lunch at Huck Finn’s Hideaway, seated beneath woodcarvings of the Big Three (Elvis, Jesus, and John Kennedy), bought a copy of Tom Sawyer at Becky Thatcher’s Book Store, and rode on toward St. Louis.

Highway 79 from Hannibal to St. Louis is another one of those roads where it’s good to have a 400F, setbacks, six speeds, a pair of K-81’s, and an engine that lives to bury the tach. It is 50 miles of road that goes up and downhill through the trees, winding up valleys and bursting into hilltop clearings with observation vistas on the river below. Euphoric and glassy-eyed from the ride, I came snarling and downshifting into Wentzville, like Hailwood pulling into the pits at Douglas, on the Isle of Man. Wentzville, Missouri, just west of St. Louis, is the home of Chuck Berry; a living legend of Rock ’n Roll.

A group of giggling 13-year-old girls on Main Street told me where Berry lived. “Just follow that road out of town. It’s called Berry Park. You’ll see it. He should be home. He was in town with his Cadillac this morning, and I saw' him shopping.” More giggling. “He’s not too popular around here any more.”

“No? Why is that?”

“Well, you know . . . he’s kind of old and everything. He’s just not. . . too cool.”

They all blushed and giggled, and I thanked them for the directions. Not too cool? Granted, I thought, he’s not Shaun Cassidy, but still . . ,

Berry’s house was right where they said it would be, about five miles out of tow n; a fenced-in country estate with a duck pond and some houses and buildings hidden back in the willows. The gate was open, so I walked up the driveway and talked to a young woman w'ho told me that Chuck was playing in St. Louis that night, at the Rainbow' Bar. As I walked back dow n the drive, a bronze Cadillac rolled in with none other than the Brown-Eyed Handsome Man himself at the wheel. He smiled and waved, if a little thinly, doubtless underawed at the novelty of another camera-carrying stranger stalking his grounds.

I found the Rainbow Bar and checked into a nearby motel. Berry was a knockout that night, playing to a cheering crowd of about 300 who’d jammed into the little roadside club. He led off with “Roll Over Beethoven,” (tell Cha-kosky da news!) “Johnny B. Goode” and “Sweet Little Sixteen”, cranking out guitar rifts that are copied by every rock musician in the world, doing his famous duckwalk and leering happily at the crowd over his earthiest lyrics.

Unfortunately, Berry is not too cool, so at two in the morning, after three frenzied encores, and despite the objections of the wildly applauding crowd, he quit playing and everyone went home.

In the bleary morning light I rode past the awesome St. Louis Arch and somehow managed to sneak out of the city w ithout being dragged off my bike by local toughs. I turned south on Highway 3. through the lower tip of Illinois. (Illinois is, subjectively, the longest state in the Union.) I crossed the river at Cairo, where the Ohio joins the Mississippi, and it is here that the river begins to Mean Business. The Ohio actually dumps in twace as much water as the Mississippi, much to the embarrassment of Mississippi fans.

I pushed south toward Memphis, where the police were on strike, the National Guard was in control, and 8 p.m. curfew w as being enforced, and thousands of people were flocking into town for the First Anniversary of Elvis’ Death; a truly irresistible combination. I camped outside the city, part of an army preparing for a daw n invasion.

I got into town early and searched out Beale Street in downtown Memphis. Once the lively bar and night-club Mecca of Mississippi Delta musicians heading north, the famous Beale Street is now' a victim of urban renewal. Only two blocks of the old street remain, and they are rundown, vacant, and boarded up. The rest is parking lots. After a moment of silence for the vanished street. I rode out to Graceland. home and final resting place of Elvis.

One year and one day after his death, a large but respectful crowd rummaged through the shopping center of Elvis memorabilia and then crossed Elvis Presley Boulevard to file up the lawn of the Graceland Mansion to see his grave. Elvis is buried next to his mother in a little alcove near the swimming pool. The grounds and grave were decorated with hundreds of floral tributes, variously shaped like gold records, hearts, hound dogs, and teddy bears. At the gate, a man was trying to sell a Harley XLCH which he claimed was one of Elvis’ stable. I shuffled past the bronze tombstone, following a family of four w ho had driven 2200 miles straight through from Nova Scotia, just to be there on the anniversary of his death. They were a day late. “It’s still worth every mile of the drive,” the man told me. “Being here is something we’ll never forget as long as we live.”

Dizzy and dehydrated from standing in line for two hours, I w'as glad to get back on the 400F and enjoy the luxury of moving air. I crossed into the flat, hot cotton country that is Mississippi’s Yazoo Delta, and is—to a Blues fan and record collector— Holy Ground.

For reasons that are unclear (something in the water, perhaps), this northwestern corner of Mississippi produced nearly every great American bluesman in the Twentieth Century. Son House, Robert Johnson, Howling Wolf, Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Charlie Patton, to name just a few', all came from a small area around Clarksdale, Mississippi. And, as if that were not enough, William Faulkner’s home at Oxford—the center of his mythical Yoknapatawpha County—lies just to the east. Never was such a small area of the earth graced with so much genius.

I stopped at a music store in Clarksdale and bought a couple of magic Fender guitar picks, one for me and one for my friend David Rhodes, who already plays guitar quite well and doesn’t need a magic pick as badly as I do. The people at the music store said that not much is left of the old music, since all the bluesmen went north in the forties. Clarksdale was not the somnolent little cotton town I’d expected. It is a bustling go-into-town-and-shop farm community, indistinguishable from a thriving county seat in Wisconsin. It has a McDonald’s and a small, but significant, suburbia.

I threw' the guitar picks in my tank bag, downed three glasses of iced tea at a little air-conditioned restaurant, and rode out of Clarksdale. Highway 61 is not exactly Racer Road as it runs through the Delta. The pavement is straight and flat, and tow ns appear on the highway as islands of buildings and trees in the sprawling cotton fields. The most visible sign of life between towns is the large number of colorful crop dusters that sweep back and forth over the road. The landscape everywhere is dotted with rusted tin roofs of old sharecroppers’ houses, many of which are abandoned, relics now on the big corporate plantations. As you ride, the air has a distinctive Fuel oil smell left by the crop dusters.

By evening I found myself in Arkansas on a river-made peninsula that is Chicot State Park. I was rather a mess, having ridden late in the day through a plague of four-winged, dragonfly-looking insects called snake doctors by the local people. These things burst on your knuckles and chin like small pigeons’ eggs. Miraculously, the park had hot showers and a laundromat. I showered, left my clothes to test the competence of the washing machine, and examined my faithful Honda. Other than lubing the chain and checking the engine oil, I hadn’t touched the bike. The oil level was unchanged since I'd left home, but the chain was sagging a bit, so I tightened it. The rear K-81, never intended as a touring tire, had vaporized about 40 percent of its tread somewhere on the Great River Road, which left me 60 percent to make it to New Orleans and home— or about the right amount.

Before leaving home I’d installed plugs two ranges colder than stock, thinking of long fast rides in the hot sun. This was a mistake, since on a trip of this kind I did much more duffing and bogging around towns and parks than 1 would do on my home turf. But the plugs looked okay, and they still worked. I adjusted my valves and cam chain and revved the engine; the 400 sounded like the same competent, enraged little sewing machine with whom I’d left home.

With clean clothes and an adjusted bike, I cruised down Highway 61 into Rolling Fork, Mississippi, the birthplace of Muddy Waters. “Yes, yes,” said one of the old men on the park bench in the town square, “I knew McKinley Morganfield (a.k.a. Muddy Waters). He was here in a big black Cadillac six years ago when his mother died. His brother Robert and his sister-inlaw Frankie live in that yellow house down the street.”

I stopped at the house and talked to Frankie Morganfield. I said that Muddy had a lot of fans up in Wisconsin and she said, “Yes, he told me a lot of you white folks like that music up there.” I laughed. “Yes, we sure do.” She thanked me for stopping and said she’d give my best to Muddy. I rode away confident that I’d done my share of tiresome meddling for the day.

At the hilltop city of Vicksburg I finally got high enough above the levees to see the river again. I rode out to the military park and cemetery, and toured the 16 miles of road that wind through the battleground. When Grant took Vicksburg, the Mississippi was opened to the Union and the war was over for the South, though the Confederacy struggled on for another two years. The graves at Vicksburg go on and on, as far as you can see; antique artillery pieces are poised at each ridge and hilltop beside bronze plaques of explanation. The battleground is one of those places where the historian could spend a year, and the passing tourist just long enough to realize how little he understands from what he sees.

The same is true of Natchez, an old, old city w ith a colorful and varied history, and a collection of beautiful antebellum homes. It is the terminus of the Natchez Trace, the canyon-like ancient trail, now paved, that cuts cross-country nearly to Nashville. I wandered around Natchez in the evening looking for a motel room, and found that everything was filled because the Corps of Engineers was in town (the Corps has built most of the levees that keep lower Mississippi towns from floating into the Gulf each spring.) I rode south to Woodville where, I was told, I could find a motel.

The road to Woodville ran through dark and hilly pine tree country, w'ith lots of traffic coming the other way. I began to assemble reasons for why I hate riding at night. I decided that they included: (1) drunks, (2) deer, (3) bright headlights that force you to ride blind down a lane that may be littered with hay bales, dead ’possums, or kegs of nails fallen from trucks, and (4) insects. By the time I got to Woodville, half of the flying insects in Mississippi had made a graveyard of my shirt and face-shield. I found a road-side motel w ith vacancy and cleaned up for my early morning sweep into New' Orleans. My room was hot, so I cranked the air-conditioner up to full and went to bed.

In the morning I woke up dreaming I’d died and gone to Alaska. The room was freezing. Feeling very refreshed, I stepped out into the steamy-hot morning at about six o’clock and rode off into the mist and dawn light into West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana. This stretch of Highway 61 passes more Southern mansions than I thought existed in all the South. With huge oaks hung with Spanish moss shading their pillared facades, like something out of Gone With the Wind, they pass by w ith names like The Catalpas, The Oaks, or The Cottage (yes, some cottage, you are supposed to think). The homes along the road became newer and less grand as I entered Baton Rouge, city of smoking oil refineries and Huey Long’s tower building. I stayed on 61 and rode along the south shore of Lake Pontchartrain to New Orleans.

I took the Vieux Carre exit, down Orleans Avenue and Toulouse Street into the heart of the French Quarter. Anxious to get off my bike and look around, I found a room at the Cornstalk Hotel on Royal Street, changed my shirt, and walked out on the town. The French Quarter, which surrounds St. Louis Cathedral and Jackson Square, is old, beautiful, and much larger in area than I expected. The Quarter is a labyrinth of narrow streets, old hotels, fine restaurants, topless/bottomless joints, night clubs, cool dark bars, souvenir shops, oyster bars, book stores, coffee houses, and expensive antique shops, all thrown together in wonderful unzoned anarchy. Music is everywhere; the great jazz clubs are open to the street. You can stand in the street, listening and watching, or sit down with a $1.50 beer and relax at the bar or a table. The music is good; not some contrived Dixieland Muzak for tourists, but genuinely well-played jazz.

I sat in Maison Bourbon, listening to the Robert Jefferson Jazz Band for a while, lunched nearby on oysters and gumbo, and then wandered down to the river, where I stumbled upon the French Market and its open-air stalls of fruits and vegetables. At the edge of the marketplace was a sight for sore and weary eyes—the French Market Cafe. I had café au lâit, chicorystyle, of course, and an order of beignets— a sort of square donut, all brought by waiters in ties and black coats. Reminded of my original goal, I looked through the nearby shops for some French roast chicory coffee, and immediately found a 1 lb. can for $2.85. Suddenly the whole trip was w'orth it. I took the can back to the hotel, locked my door, and carefully packed the coffee away in my tank bag. All that remained was to get it home.

I counted my money, found that I had $32 left, and suddenly realized that my trip home was going to be, of necessity, a straight shot of dreaded Interstate, with few food and rest stops. I had just enough money for gas and a couple of Big Macs.

On an early Sunday New Orleans morning, w'ith the streets nearly vacant, 1 rolled out of the Vieux Carre, turned North onto 1-55, snicked the 400 into sixth gear, and opened all four throttles. I was all buzzed up and ready to ride, speeding on four cups of black coffee. I rode and filled my tank, rode and filled my tank, stopped for a Big Mac, and rode and filled my tank until it was too dark and cold to ride. Just south of St. Louis, after 14 hours on the bike, I pulled off the I-road, rolled up in my tent behind an abandoned gas station, and slept. I got back on the bike at 5:30 a.m., filled my tank, drank more coffee, rode my bike, ate a Big Mac, and rode like an express train.

Thirty-four hours after leaving New Orleans, I entered Wisconsin with $5 in my pocket and the 400 still running like a champ. I patted the side of the tank with my sunburned hand and said, “This is a very, very good motorcycle.” The odometer showed just over 11,000 mi., or 3,000 more than I’d left with. I was burned-out, punch-drunk, and traveling in a senseless state of tunnel-vision from the long ride, but as I crossed the border I still managed to grin. My bike was running perfectly. I hadn’t been issued a single traffic ticket, my bald rear tire was still holding air, I’d not met even one unpleasant person on the entire trip, despite vague and shadowy warnings to the contrary, and there had been, incredibly, no rain in seven days on the road. But, best of all, I knew that buried deep in my tank bag was a $2.85 pound of Louisiana French roast chicory coffee, with a Wisconsin street value of nearly $6.