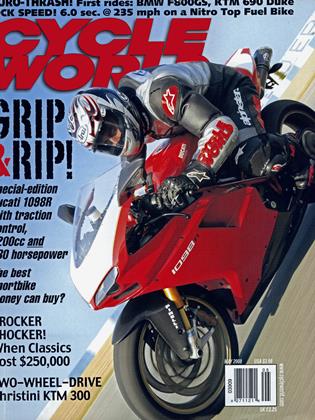

THE TOP-FUEL EXPERIENCE

RACE WATCH

Warp speed on a fire-breathing, nitromethane-burning land missile

KORRY HOGAN

AT THE FLASH OF YELLOW, I SNAPPED MY RIGHT ARM TOWARD THE ground and the bike lunged forward. All four “candles” were lit and my spine was smashed against the seat, leaving my legs dangling weightlessly behind me. Out of the corner of my eye, I caught a glimpse of Larry “Spiderman” McBride, then seven-time AMA/Prostar Top Fuel champion, in his distinctive web-covered helmet and leathers starting to pull away from me.

That’s when I quite literally got the shock of my life-80,000 volts. I was being electrocuted, the result of a broken sparkplug. My body felt as if it were being ripped apart, one muscle fiber at time. It was the most horrific thing I’d ever experienced. As my arms went limp, I did what came naturally: I let go of the handlebar. The bike and I then parted company, and as I tumbled down the track at 180 mph, the last thing I remember was sliding past the finish-line tower-upside down. I closed my eyes and prepared for the worst.

Thankfully, the “worst” wasn’t nearly as bad as I feared.

A year earlier, at the end of the 2005 AMA/Prostar season, I’d made plans to slow down. I’d won back-to-back Funnybike championships, run a few of the fastest passes in the history of the class and been named Professional Rider of the Year. I’d accomplished a lot, charged up a few bills and decided it was time to move on to other things. In a true act of finality, I sold my bike to a fellow drag racer in Sweden.

I was still mulling over my options when one morning I received a phone call from five-time AMA/Prostar Top Fuel Champion Tony Lang. He wanted to know if I would like to ride a Top Fueler. “Yes!” I replied without a moment’s hesitation. The bike in question belonged to Mike Dryden, whom I’d never met. But as it turned out, Tony’s former crew chief, John Alwine, would be doing the tuning, so the project appeared to be in good hands.

My first contact with Mike’s $ 150,000 Top Fueler came several months later at a track in Richmond, Virginia. It was an experience I will never forget. The bike itself, with its long wheelbase and mammoth rear slick, was intimidating enough. Factor in a supercharged, nitromethaneburning four-cylinder engine making 1200 horsepower-Avzce as much as my old stock-crankcase, Suzuki GS1150-based Funnybike-and you have something that is anything but run-of-the-mill. Think landbased missile.

As I swung a leg over the bike and settled into the saddle, the engine was popping and cracking loudly, and the entire motorcycle was shaking violently. So, I thought, this is what a Top Fuel motorcycle feels like-at idle.

In the pits, Mike and John gave me a brief rundown of what they wanted me to do: Pull in the rear brake (Top Fuelers run centrifugal clutches, so both front and rear brakes are controlled by handlebarmounted levers) and slowly bring up engine rpm to seat the clutch. As soon as I gripped the throttle, though, my brain stopped communicating with my wrist. When I finally screwed up the courage to crack open the throttle, the engine instantly came alive, the clutch engaged and the bike tried to jump off the work stands.

The following day-my 29th birthdaywith some understanding of what I was up against, my greatest fear wasn’t rocketing down the track at four times the national speed limit. Rather, it was performing the requisite burnout. I have plenty of experience with long, smoky burnouts. On my Funnybike, they’d become routine: Squeeze the clutch lever, select third gear, clamp all four fingers of my right hand around the front brake lever, wing the engine to 12,000 rpm and dump the clutch. Easy.

As I straddled the bike in the burnout box, Mike signaled for me to put the transmission into gear. John made a last-minute fuel adjustment and patted me on the leg. I double-checked that Ed selected high gear and took a few deep breaths. “Okay,” I told myself, “don’t give it too much throttle. An eighth-turn should be enough.” To my relief, everything went smoothly, just as McBride, a three-decade veteran of the class, told me it would. I snapped open the throttle and the 14-inch Mickey Thompson slick grew skinny in a hurry.

What Larry failed to mention is that once a Top Fuel motorcycle is “up on the tire,” it tends to get a bit squirrelly. As soon as the bike began to roll forward, the rear end stepped sideways. By the time I closed the throttle, Ed missed my mark. At least the burnout was behind me.

Weeks later, I tried to recall how I had felt after my initial burnout, but for some reason, I couldn’t. Could it possibly have been that forgettable? Just another walk in the park, so to speak, for a ’strip vet? Not a chance. More likely, the fumes from the nitro had been so strong that the experience never reached my brain’s memory banks.

Em not kidding: When I chopped the throttle and grabbed both brakes, bringing the bike to an abrupt halt, Ed just made my first rookie mistake. Because the rearfacing exhaust exits through the tailsection just behind the rider, the noxious fumes quickly found their way past my open faceshield and into my helmet. With pump gas, that’s no big deal. But with $50-pergallon nitromethane (five gallons per pass), it’s like a taking a shot of pepper spray directly in the face.

My eyes instantly began to bum and my throat swelled shut, cutting off my oxygen supply. I started to panic. In a moment of clarity, I slammed my faceshield closed and let my helmet’s respirator do its job. Lesson learned: Don’t breathe in when you’re being pushed back to the start line after a burnout.

As emotionally rattling as that experience had been, it in no way prepared me for what came next during my first actual ride on the MTC Engineering machine in Memphis, Tennessee. I was there to earn my Top Fuel license, and nothingnot even countless 6-second, 200-mph passes on a Funnybike-could have primed me for my first quarter-mile run on one of these monsters.

Sitting on the starting line, burnout complete, I absorbed my surroundings. The engine settled into a rhythmic lope, each beat pulsing in cadence with the whine of the supercharger. I calmly reached down from the left handlebar to the air shifter back into low gear.

Mike instructed me to roll forward, stopping me a few inches shy of the first start-line staging beam. There, he made last-minute fuel adjustments and armed the data-logging system. When he finished, fuel was being fed into the engine at a different rate, and the bike suddenly took on a new, even more violent personality-he had awakened the beast. He then gave me a quick pat on the leg, yelled something inaudible and left me alone to do what I was there to do: ride.

After Mike walked away, a feeling of nervous excitement washed over me. I felt as if I were in one of those situations in life where something had gone very wrong and I had no control over the outcome. But I was committed. I couldn’t back out.

I rehearsed my plan: Take deep breaths, slam the throttle wide-open, hit the shift button 2 seconds into the run, flex my abdominal muscles to keep my core straight and my neck from snapping backward. I focused on the Christmas tree in the center of the track and tripped the first beam. Six more inches and it was “go” time.

I pushed down on the top of my helmet, quadruple-checked that my visor was closed and tip-toed into the second beam. Yellow flashed on the tree. What happened next-the initial “hit”—is difficult to put into words. Think of it like this: You’re sitting in your car at a stoplight when you’re suddenly rear-ended by a semi-truck traveling at full speed. That’s close.

A Top Fuel bike accelerates from 0-60 mph in less than 1 second.

That’s impressive. But what really got my attention, what nearly popped my eyes out of my head, was what happened after I made the shift from first to second gear. It was as if I’d suddenly been handed 800 more horsepower while traveling at more than 100 mph!

When I made that same shift on my Funnybike, the power delivery was always smooth and linear.

This was so different that I thought Mike and John had played a sick trick on me, letting the bike lollygag through first gear then giving it full steam as soon as I made the shift to second. The abruptness of the power caught me off-guard, and the bike started to veer to the left toward the retaining wall. At that point, instinct took over. I kept the throttle pinned and jerked the handlebar to the right.

Top Fuel Lesson #2: These bikes make twice as much power and weigh 350 pounds more than a Funnybike. They don’t react to “jerking” the handlebar. This would have been a good time to remember what McBride told me about using my feet to steer the motorcycle. Luckily, I’d been instructed to shut off after punching second and passing the 330-foot mark. When I shut the throttle (yes, contrary to urban myth, dragbike throttles work in both directions), the bike began to react to my inputs-almost as if it were just another motorcycle. I coasted through the lights in 10.15 seconds at 85 mph. As I passed through the end of the track, I pulled the fuel-shutoff pin and let the engine choke itself out. My Top Fuel career was officially under way.

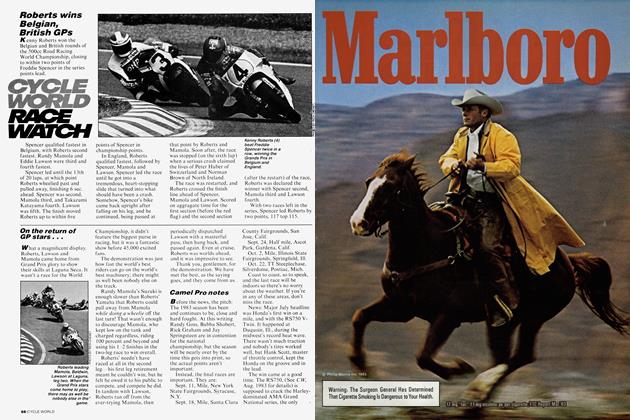

Six months later, at the 2006 AMA/Prostar Pingel Thunder Motorcycle Nationals at Indianapolis Raceway Park, I was matched up against none other than Larry McBride and his mad-scientist tunerbrother, Steve, in second-round eliminations. We knew we weren’t going to beat Larry on a fluke; we would need to put a heavy tune-up into our bike and go for broke. For the first time in my short Top Fuel career, though, I wasn’t nervous. In fact, I was actually looking forward to doing battle with a living legend. As my dad helped me into my leathers, he said something I will never forget: “Remember, this is fun. You are going to go out and have a good time.”

I climbed on the motorcycle and tried to maintain my focus. With a few rotations from the outboard starter, the engine rumbled to life. Gasoline soon gave way to nitro and the bike took on its “normal” freakish form, belts and gears whining under the stress of the heavy explosions taking place within the combustion chambers.

Mike gave me the okay to start the burnout. With a flick of my wrist, the bike was instantly up on the tire, smoke billowing from under the tailsection. With heat in the clutch, engine and tire, it was time to get down to business. I clicked

the transmission into low gear, and Mike and Darren Brinkman began the long push back to the starting line. Mike motioned for me to move the bike to the right a bit to get into our chosen groove, and I snapped my visor shut.

I slowly brought up the engine rpm to tickle the clutch and the bike began to creep forward toward the starting line and my date with Larry. It was at that moment that everything suddenly became deathly quiet. I couldn’t hear anything-the engine, the crowd, not even Mike. My top light on the Christmas tree illuminated, and Mike reached across the bike and turned on the fuel-enrichment valve and armed the data-logger. I waited for Larry’s light to come on before I began to toe in. When my second bulb popped, I inched a little farther forward; if I was going to have a shot at beating Goliath, I would have to chop down the tree. Larry toed in, and at the first sign of yellow, I buried my right elbow into the ground. My bike banged onto the wheelie bar and left harder than ever. Just as I passed the 60-foot mark, though, it began to fishtail violently. Larry pulled alongside and, my bike having stabilized somewhat, I passed through the eighth-mile mark right on his heels. I tried to make myself as aerodynamic as possible, but our engine dropped a couple of cylinders and he pulled away. Even so, I made a 6.17-second pass at (only) 220 mph. Not only was it my personal best, it was the 1 lth-quickest run in motorcycle drag-racing history.

Over the next year, Larry and I raced each other several times, the most infamous coming at the 2006 season-ending AMA/Prostar Drag Racing National Championship in Gainesville, Florida, where I was nearly cooked alive by that superhigh-energy sparkplug arc and slid through the timing lights on my head at 183 mph. Every time, for one reason or another, he got the best of me-as well as everyone else who raced against him.

Then, last August, back at Indy, everything came together. Going into the weekend, we were in good shape. We had two healthy engines, and our sponsors had pulled out all the stops getting us the spare parts we needed. Turnout for Top Fuel was anemic, so we played it safe in the first round of qualifying on Saturday. When one of the cylinders loaded up, though, I had to shut off early. Midway though my second pass, the primary belt snapped, and I veered offtrack and down the return road with a broken motorcycle. Was this an indication of how things were going to go the rest of the weekend? Sure enough, our Sunday shakedown went poorly, too, the engine once again dropping a couple of cylinders. At least we were able to squeak out a 200-mph pass, which helped calm my nerves going into the final against Larry.

McBride led from the get-go. I was late leaving the line, and the bike felt sluggish. As we approached the 300-foot mark, it started to fishtail with the front wheel hiked up in the air. All of sudden, Larry disappeared from my peripheral vision. I pressed my helmet against the frame backbone and tried to make myself as small as possible. Then my bike started to drop a cylinder.

“No!” I screamed in my helmet. Five feet from the finish, I could hear Larry coming fast. He passed me with such fury that I felt like I was sitting still. But it was too little, too late. I won with a 6.30second, 215-mph pass versus Larry’s 6.39 at 230.

Beating Larry McBride tops my list of racing accomplishments. As with anything in life, though, there is always room for improvement. Larry and Jimmy Brantley are the only people who have run a 5second quarter-mile on two wheels. I want to add my name to that list. AMA/Prostar Top Fuel champion has a nice ring to it, too.