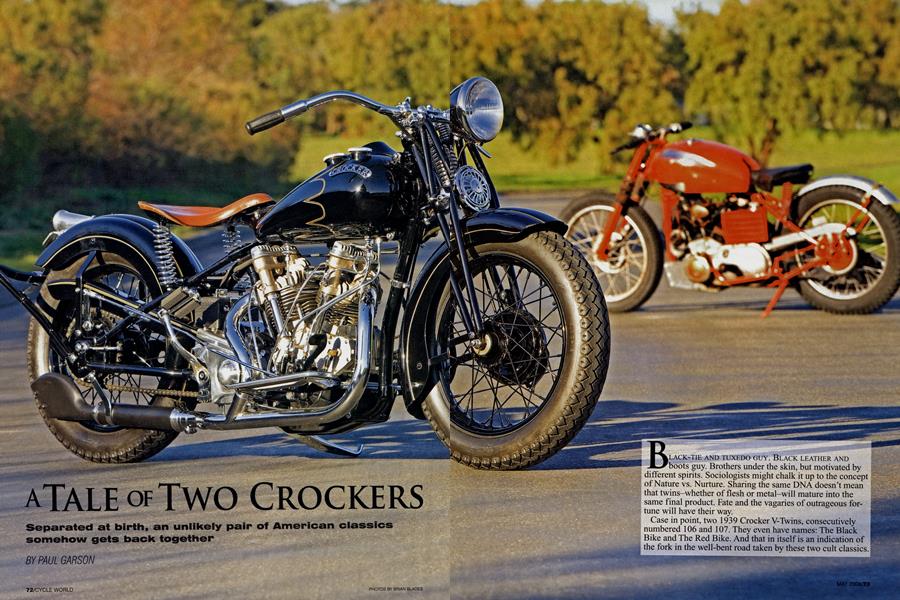

A TALE OF TWO CROCKERS

Separated at birth, an unlikely pair of American classics somehow gets back together

PAUL GARSON

BLACK-TIE AND TUXEDO GUY. BLACK LEATHER AND boots guy. Brothers under the skin, but motivated by different spirits. Sociologists might chalk it up to the concept of Nature vs. Nurture. Sharing the same DNA doesn’t mean that twins-whether of flesh or metal-will mature into the same final product. Fate and the vagaries of outrageous fortune will have their way.

Case in point, two 1939 Crocker V-Twins, consecutively numbered 106 and 107. They even have names: The Black Bike and The Red Bike. And that in itself is an indication of fork in the well-bent road taken by these two cult classics.

As the reigning Holy Grails of the current vintage motorcycling feeding frenzy,

Crockers set sales records at two recent auctions, one at the Otis Chandler Museum in Oxnard, California; the other at L.A.’s Petersen Museum, to the tune of more than $250,000 each when buyer’s premiums were levied. A third bike, posted on eBay and seeking an international audience, also fetched a bid of $250,000. For the price of a nice island off Costa Rica, collectors are pistol-whipping each other to own one of the bikes built by a maverick American designer/ entrepreneur by the name of Albert Crocker.

An Indian dealer in late-1920s Los Angeles, Crocker ventured into building his own machines with the aid of Paul Bigsby, a talented engineer/designer. They produced some successful single-cylinder speedway bikes, then launched their unique vision of a sporting V-Twin in 1936. Using aluminum components and a stout engine design, the bikes epitomized power-to-weight performance, Crocker fans extolling the bike’s virtues as far exceeding those of their contemporaries, Indian and Harley-Davidson. The first Twin, a 61-cubic-inch (lOOOcc) hemi-headed version, produced 40 horsepower in a machine that tipped the scales at 480 pounds. Features included each cylinder’s two pushrods sharing a common tube, and the transmission housing as an integral part of the frame. Claimed top speed was 110 mph. The 1930’s price tag was $500 to $600 depending on options, a hefty sum in those days.

The last batch of Crockers, using an improved non-hemihead design, was produced in 1940 as WWII sucked up precious materials. Compounding the problem was simple economics: Crocker was losing money on each bike he built. A few were made from “seconds” parts before the company ceased to exist. Perhaps 60 Crocker V-Twins were built, the number in dispute. Not their current value, however.

With Crockers now fetching astronomical, quarter-million-dollar sums, it’s no wonder that people will wander the world in pursuit of these rare and charismatic machines. So intense is the desire among serious collectors to own a Crocker that one intrepid Australian of our acquaintance had himself ’coptered into the jungles of New Guinea running down a rumor that a Crocker purportedly owned by a U.S. navy man had been left on the island during WWII. After traipsing around the bug-andbeast-infested landscape, he did come upon rusted wartime relics but no Crocker. The adventure ended in true Indiana Jones fashion, our man literally just reaching the safety of the awaiting rescue helicopter with machete-swinging locals giving chase. The people who hanker after Crockers for their unique character are often characters themselves.

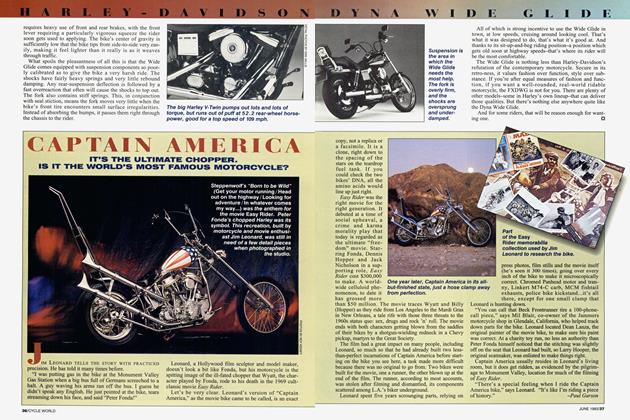

THE BLACK BIKE

Fortunately for all involved, the Crocker “Black Bike” was relocated from far more congenial climes by Glenn Bator (www.batorinternational.com; 805/646-9556), a major mover and shaker, buyer and seller, in the world of vintage, classic and antique motorcycles. After long and persistent efforts, not to mention bagfuls of U.S. dollars, it was brought back home from its decades-long “vacation” in Italy. Bator himself calls bucolic Ojai, California, home and headquarters, and from there launched a mission that would first take him to England then to the Continent and up the boot of Italy.

Reaching Milan, he met up with Massimo Zavaglia, restorer of the Crocker, an artisan of the highest caliber. In the company of Massimo and his wife Maria Luisa, who translated for the group, Bator toured several bike collections, including Massimo’s own treasure trove of vintage iron.

Finally the moment arrived, the focal point of the entire expedition. Bator would have his first up close and personal look at the Black Crocker and speak with owner Luccano Lanfranchi, who happens to be a high-ranking Italian politician and well-known art collector.

As to its recent history, this Crocker, serial #107, had been in Italy for about 20 years, but during that time the engine had been yanked and sent back to the States where Ernie Skelton, a Crocker guru in Southern California, rebuilt it. Lanfranchi then commissioned Zavaglia to restore the chassis and reinstall the motor. After a period of two-and-a-half years and some 1400 hours of restoration, the completed bike was returned to Lanfranchi, who was so moved by the quality of the work that he reportedly bent over and kissed the gas tank, and exclaimed that it was “an absolute work of art...an absolutely fluid, perfect restoration.”

Arriving at the location where the Crocker was stored, Bator and friends found themselves in a cul de sac flanked by four massive buildings, each with six monumental garage doors.

Bator picks up the story: “Suddenly one slid open and standing there is a huge Italian guy. The guy definitely has the bodyguard persona going. He turns and begins wheeling out the Crocker into a 40-by-40 brick courtyard with these buildings looming over us. I’d seen photos of the bike and thought I knew what to expect. But it was beyond any picture. When I looked it over, the workmanship was on par with the world-class, upper-echelon level of restoration. Stunning. Phenomenal.”

Drama on high, someone then handed Bator a phone. “It was the bike’s owner, Mr. Lanfranchi, who happened to be in Switzerland. We talked about the bike and he gave me a bit of the history. And then I learned that whoever buys the bike, the money is being donated to charity. Very nice on his part. Bottom line, it was a done deal as soon as I saw the bike, but I also knew he wasn’t going to negotiate, so I stepped up large. Big money but worth every lire.. .make that euro. The deal was struck and I owned a Crocker, at least until someone stepped up a bit larger.”

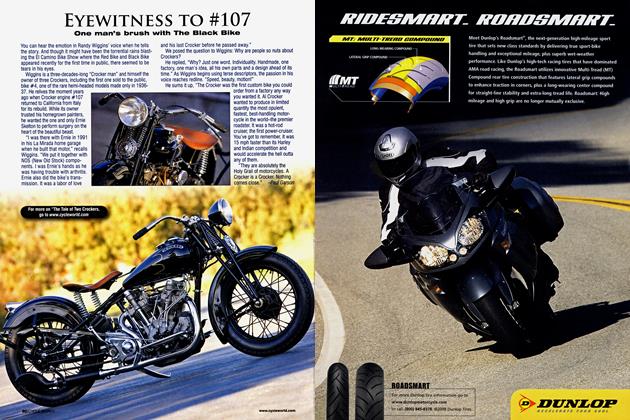

THE RED BIKE

We’ve all heard the proverbial “bike in the barn” story; this one goes under “bike in a shed.” As Bator tells it, he gets a call from a fellow who works for a utilities company in Fort Collins, Colorado. For several years, the guy’s been reading an elderly gentleman’s meter and now that person wished to sell some old motorcycles moldering away in his shed. The helpful utilities man sees one of Bator’s ads and rings him up.

Says Bator, “Over the phone he begins listing the bikes.. .an Ariel Square Four, okay, nice...next? A Harley XA.. .okay, nice bike... next? There’s an Ariel basketcase.. .okay, parts.. .next? Then he says, ‘Oh, then we got a Crocker.’ At that point, my ears stand up. He says it’s in some English frame but doesn’t know too much about it, he can send some pictures.”

The photos arrived, including some close-ups of the motor. This is where things get a little weird.

“I noticed the engine number,” says Bator. “What the...? It was only one number off the Black Bike’s serial number, #106, a consecutive bike! What are the chances of that happening? It was almost a little spooky. I could not believe it.” When he logged onto the Crocker Registry, Bator learned that #106 was listed as unknown, missing in action. In effect, he had unearthed a long-lost Crocker, the sibling to one he had just purchased from Italy. (By the way, that previously mentioned Crocker posted on eBay? It happens to be #108!)

Word was that the original owner had several Crockers back in the day, but for this incarnation he started out with just a motor bought out of California back in the early ’50s, perhaps after the donor bike had been crashed. Notes Bator, “It’s a 1939 61-cubic-inch Twin the guy had stuffed into a pre-war hardtail Triumph frame. It’s also got the Triumph front end as well as the four-speed transmission, but was fitted with an Ariel gas tank.”

The frame was from a single-cylinder model so the

engine cradle was quite small. To get the Crocker V-Twin to fit, the bottom rails were done away with and engine-mount plates were fabricated, plus the downtube was spliced, re-angled and gusseted.

“It was quite a neat design idea and something I had not seen before,” says Bator. “After a quick check-up, I fired it up and rode it. It smokes like a banshee probably because it’s been sitting forever, maybe dropped a ring. But it felt like it had all the power in the world, and since it’s set up in a shorter frame, it handled really well.”

APART AGAIN

As this article was being prepared, both bikes were sold and split up. After failing to meet Bator’s reserve price at the Petersen Museum auction in late 2007-a turn of events he blames on the declining economy-Crockers #106 and 107 have since gone to new homes. The Black Bike is now on display at Virgil Eling’s increasingly impressive Solvang Vintage Motorcycle Museum (www.motosolvang.com) just north of Santa Barbara-well worth a stop if you’re on the way to the Laguna Seca MotoGP. The Red Bike went to the Midwest, now part of Scott Hall’s private collection in Wichita, Kansas. It sold for a rumored $80,000, which has to be a world record for a bob-job crossbreed.

Bottom line, whether typified by a pristine 100-pointer or a scruffy special, the Crocker mystique-along with the depth of the pockets needed to own one-only deepens with each passing day.

Paul Garson, a writer living in Los Angeles, cannot afford a Crocker of any sort on Cycle World ’s freelance rates.