SERVICE

PAUL DEAN

Compression anxiety

Q I have questions regarding strapping down a motorcycle for transport. Some people have told me that the usual method-compressing the fork with straps-can cause long-term damage to the springs and dampers, and, of course, it also can “blow out the fork seals.” Is this possible? I’ve transported bikes many thousands of miles and never had a problem. Aren’t forks compressed in their original shipping crates for weeks (or even months)? Are the fork seals actually pressure seals or are they just scrapers designed to keep the fork oil where it belongs? I’ve seen people employ incredibly elaborate strapping systems just to keep the bike stable without compressing the forks. Are they doing the right thing or just helping to keep the tiedown-strap industry healthy?

Matt Rosen Madison, Wisconsin

A Realistically, tieing down a motorcycle in a reasonable manner for a typical period of time causes no harm to the fork’s springs, dampers or seals. By “reasonable,” I mean that the fork is compressed only as far as is necessary to keep the bike from tipping over or moving side-to-side excessively; and by “a typical period of time,” I mean that the bike is tied down only as long as is needed to complete its transport-to and from a racetrack or riding area, during a move to another city or state, etc.

If, however, the bike is strapped down so firmly that the fork is completely compressed, and if it stays in that condition for extended periods-weeks, months or even longer-then it is possible that the springs may weaken somewhat. But they also may not. It all depends upon numerous factors, including the age of the springs, the quality of the metal in the springs and the condition of the springs before the bike was tied down.

Don’t forget, fork springs always are under some kind of load, in many cases, even when the bike is not being ridden; they do, after all, hold the front of the bike up. Putting them under additional load for comparatively short periods is not likely to significantly change their rate. Springs do wear out, but usually only after many years of usage.

And the notion that the dampers or seals will be damaged by having the fork compressed is nonsense. The dampers do absolutely nothing when oil isn’t passing through them; in a steady state, such as when the front end is tied down, they undergo no wear or stress whatsoever. And if the fork seals can endure the tremendous pressure of the spike loads the damping oil is subjected to during everyday riding, they are not going to be affected by that same steady state.

Years ago, the first servo-driven, computer-controlled suspension dynamometers were able to take real-world data gathered by sensors on a bike’s suspension system and replicate the exact forces that a fork or shock had to undergo in actual use. The operators of those dynos were dumbfounded to learn that the spike loads of damping were as much as seven times greater than they had ever before imagined. If a suspension can withstand that kind of abuse without sagging, leaking or breaking, being tied down on a truck or a trailer is not likely to hurt it.

And yes, the forks on many bikes are indeed compressed in their shipping crates as they travel from the factory to the distributor’s warehouse and ultimately to the dealer. Even then, the bike may remain in the crate, stored in the dealer’s warehouse for quite some time until it is removed and assembled. So, unless you tie down a bike as though you expect it to survive a Category 5 hurricane not scheduled to arrive until late in 2010, don’t lose a lot of sleep over the potential damage to the front suspension.

Patches and pies

Q Stevie, Stevie, Stevie! In his report on the 2009 Harley-Davidson CVO Dyna Fat Bob (“Milwaukee’s Factory Flare,” October Roundup), Steve Natt said: “Super-chubby tires offer lots of contact patch...” Impossible! This kind of physics-rescinding dross I expect from Hot Bike but not Cycle World. I’m sending Archimedes over immediately to slap you across the chops with a copy of his “Principles of Buoyancy.” For shame; no raisin pie for you!

Jeff Cottrell Savannah, Georgia

A If I am one of the CW staffers who shall be deprived of raisin pie, I thank you from the bottom of my empty stomach; I hate raisins.

Meanwhile, Steve Natt’s mention of the contact patches on the 2009 CVO Fat Bob were in reference to their quantity, not their quality. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist (or Archimedes) to figure out that wider tires (a 180/70 rear on the Fat Bob as opposed to a 160/70 on the other Dyna models, and a 130/90 front instead of a 100/90) provide a wider contact patch. And even though both of the Fat Bob’s tires are 16-inchers and the other Dynas have a 19-inch front/ 17-inch rear combination, the aspect ratios have not changed; so the Fat Bob’s fatter tires end up slightly taller, as well. A taller tire has a greater circumference, and that, too, provides more contact-patch area.

We here at Cycle World fully understand that a larger contact patch is not necessarily a better, grippier contact patch, especially if everything else about the affected motorcycle, including its weight and weight distribution, remain the same. But Natt’s “lots of contact patch” was strictly referring to area, and for that he owes no apologies-and neither do we.

Got any lemon meringue?

German chocolate? Apple, even?

Who let the dogs out?

QI have a question about gear dogs. What the heck are they, anyway? You’ve mentioned them before in Service, and I’ve read about them in tests in your magazine and others, but I don’t understand what they do and why they do it. Any chance you could explain these things in language a technically challenged person like me might understand? Adam Fuller

Schenectady, New York

A Certainly. In some motorcycle transmissions, gear dogs are the little pegs on the sides of certain gears. In other cases, they are little pegs on the sides of a separate engagement device on a transmission shaft. But in all cases, the purpose of these dogs is to en gage mating dogs or open slots on adja-

cent gears.

The accompanying illustration shows the three most common gear-dog arrangements. All three engage or disengage their adjacent gear or gears by being slid to one side or the other when the rider moves the shift lever. The dog-to-dog type uses matching dogs on adjacent gears; the dog-toslot type engages by sliding the dogs on one gear into slots on an adjacent gear; and instead of having the dogs on a sliding gear, the dog-ring type mounts them on a dedicated engagement device that is moved side-to-side by a shift fork.

Candid Cameron

Q I’ve been wondering what the value of a MotoGP bike is in U.S. dollars. Is it really close to $10 million as some people claim, or are those bikes even more expenI’m not mistaken, one of the motorcycle magazines said that a satellite team had to pay $120 million for a bike only. Is that correct? Hendra Suwardhana

Seminole, Florida

A Most of what I can tell you about this is second-hand information, but here goes. Back in the days of 500cc two-stroke racing, the usual charge to a satellite team, per “seat” (meaning two bikes, plus certain spares and services, all to be returned at season’s end), was about a million dollars. Back in 1981,27 years ago, I was next in line behind the Honda guys at a border crossing and “just happened to see” the valuation on their carnet. It listed the value of each NR500 (the oval-piston four-stroke V-Four) at one million U.S. dollars.

Now jump forward to the MotoGP era, when Claudio Domenicali of Ducati told an interviewer that he believed it would cost Ducati U.S. $35 million to get in (meaning to develop the necessary equipment) and about $10 million annually for operations. Two rumors from 1997, the year Honda won World Supers with the RC45, held that they had spent either $10 million or $17 million on development for that bike, in that year.

So, how would you value a MotoGP bike? One way would be to add up all development, production and spare-parts costs, then divide by the number of machines built.

Just for fun, as I recall, Honda back in the 1960s spent $285,000 to develop its twincylinder 50cc racer.

As typically a team will build four or more machines for its own use, plus some at a slightly lower specification for satellite teams, the “price” might be something like annual spending, divided by 10. That would suggest a figure of $2-3 million per bike, which “feels” about right in comparison with numbers from the two-stroke era and factoring in the increased complication of the current four-strokes. -Kevin Cameron

Usually-but not always-the gear-dog device that slides back-and-forth is splined to its transmission shaft, and the mating gear or gears beside it are not. When the dogs are not engaged, the adjacent gears freewheel; but when the dogs are engaged, the two turn as a unit, providing the selected gear ratio.

Like, groovy, man

QI currently ride an old lead sled, a Honda CB900C running on Metzeier ME880 front and rear tires that I keep inflated to 36 psi. Though my overall experience with the tires has been favorable, several sections of the highways here in Utah have grooves cut into the surface parallel to the direction of travel to aid rain-water dispersion.

When I come to these sections, I have to slow way down, as the front and rear end can get squirrelly. The Utah highway department tells me that these grooves should not be a problem, but I’ve spoken with a few other riders who have had similar experiences. Can you shed some light on this issue? Ken Koons

Farmington, Utah

A Absolutely. Many of the road surfaces in Southern California’s extensive freeway system have been raingrooved for decades, so we are quite > familiar with their effect on motorcycle handling. Some bikes have steering geometry that makes them more sensitive to such surfaces than others, just as some tires have a distinct disdain for rain grooves while others ignore them.

In the majority of cases, the wiggling a rider experiences is caused by interaction between the grooves in the road and the grooves in the tires. The edges of the tire grooves alternately catch and release on the edges of the road grooves, resulting in minor steering inputs that make the bike feel a bit twitchy. Tires with circumferential grooves around the center of the tread tend to be the most sensitive, while tires that have no such grooves usually are least affected. But not always. Certain tread patterns involve blocks of rubber that squirm slightly on grooved surfaces, and even the carcass construction of some tires causes them to react to the small shifts in contactpatch pressure caused by rain grooves.

So, too, can the condition of your bike be a factor; after all, your Honda is more than 25 years old (the CB900C was only built from 1980 to 1982). Loose or worn bearings in the wheels, the steering head or the swingarm pivot can exaggerate the rain-groove “boogie,” and ditto for rearwheel misalignment. I’ve had other riders tell me that Metzeier ME880 tires work exceptionally well on rain grooves, so perhaps the problem is more with your bike than with its tires.

No matter the cause of the wiggle, the best strategy to apply when it occurs is to do...nothing. Don’t panic, don’t try to overcome the wiggling, don’t tighten your grip on the handlebars. Just relax and let the bike do its little dance. The more you tighten up, the worse the movement becomes; the waggle of the front end then gets transferred directly into the rest of the chassis via your stiffarmed grip on the bars, energizing the side-to-side movement of the whole bike. But if you just loosen up and ride as you always do, the wiggling will be minimized; and in any event, nothing bad will happen. As a staff, we’ve ridden hundreds of thousands of miles on rain grooves aboard hundreds of different motorcycles fitted with countless different brands and types of tires, and not even once has anyone crashed or lost control as a result.

WFO is NFG

Q I have a 2003 Suzuki SV1 000S that has about 35,000 miles on its odometer, and it has a performance problem that occurs when I try to use full throttle in any gear. The bike accelerates, but not as quickly as it should. It almost feels like I’m dragging the brake. But if I roll the throttle back about a quarter-inch from full stop, the bike jumps forward like the “brake” has been let off.

Since I live in an urban area, this is a pretty trivial problem most of the time because I’m rarely, if ever, at full throttle. But when I take weekend trips on open roads, it becomes an annoyance. Any insight you might offer would be appreciated. Benjamin Johnson

Salt Lake City, Utah

A To meet the requisite exhaustemissions standards, a vehicle must run through the EPA’s standard Driving Cycle, a computerized dynamometer test created with an automobile decades ago. The test involves a legal, everyday driving pace that does not require larger-displacement motorcycles to come even close to full throttle and high rpm. But at the smaller throttle openings and lower rpm used during the test, the fuel-air mixtures often have to be quite lean for the engine to pass. Lean mixtures make an engine run hot; so to help keep an already-hot engine from overheating if the rider suddenly starts to ride more aggressively, the manufacturers tend to calibrate full-throttle mixtures either spot-on or even a little rich.

When most motorcycles were carbureted, it was common for some to exhibit the condition you describe, especially at higher altitudes. The full-throttle mixtures were barely suitable for sea level and altitudes up to a couple of thousand feet, but above that, those bikes would accelerate better at three-quarter throttle than they would at full throttle.

Fuel-injection largely remedied that problem because it can selfadjust the mixture within the limits of its fuel mapping using input from the various sensors located around the bike. So even though the full-throttle mixture on an EFI-equipped motorcycle might be a bit rich at sea level, it usually gets proportionately leaner at higher altitudes as the system adjusts for the reduction in air density.

Salt Lake City’s elevation is more than 4200 feet, as is most of the area around that part of Utah, and even the lower levels of the state are in the 3000-foot range. It’s likely, then, that most of your riding takes place at higher altitudes. So, my guess (and it’s just that) is that your SV1000 has a faulty sensor, probably the ambient air-pressure sensor. If that sensor is not reading the altitude (i.e., air pressure or density) with any degree of accuracy, the mixture could be just about as rich at 4200 feet as it is at sea level. A capable Suzuki dealer should be able to run a diagnosis on your SV to determine if that $ 100 sensor-or perhaps another one-is at fault.

In the event that neither you nor your dealer is able to find fault with the SV’s EFI, consider installing a Power Commander (PCIII USB, part #314-411; $350). That’s a relatively expensive fix for your full-throttle problem, but a Power Commander also allows you to adjust the fuel mixture at all rpm and throttle positions. With a little experimentation, you should be able to sharpen your SV 1000’s performance in other areas, not just at full throttle. □

Got a mechanical or technical problem with your beloved ride? Can’t seem to find workable solutions in your area? Or are you eager to learn about a certain aspect of motorcycle design and technology? Maybe we can help. If you think we can, either: 1) Mall a written inquiry, along with your full name, address and phone number, to Cycle World Service, 1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach, CA 92663; 2) fax it to Paul Dean at 949/631-0651; 3) e-mail it to CW1Dean@aol.com; or 4) log onto www.cycleworld.com, click on the “Contact Us” button, select “CW Service” and enter your question. Don’t write a 10-page essay, but if you’re looking for help in solving a problem, do include enough Information to permit a reasonable diagnosis. And please understand that due to the enormous volume of inquiries we receive, we cannot guarantee a reply to every question.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

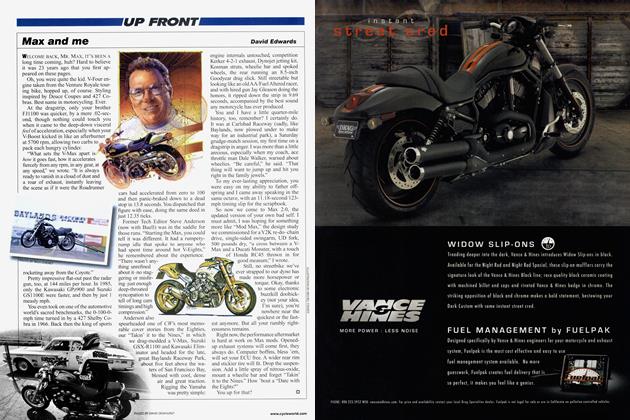

ColumnsUp Front

December 2008 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsThe Great Wisconsin Fly-Over Tour

December 2008 By Peter Egan -

TDC

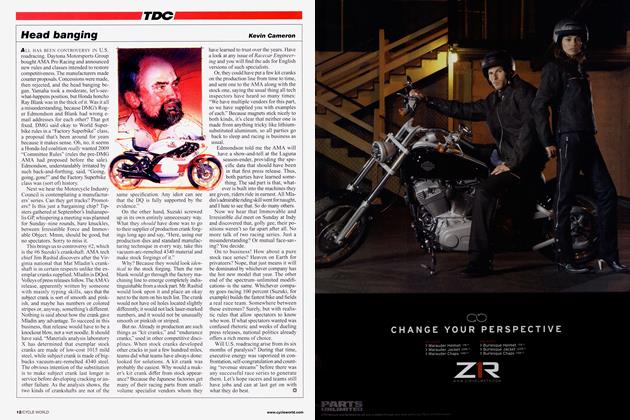

TDCHead Banging

December 2008 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

December 2008 -

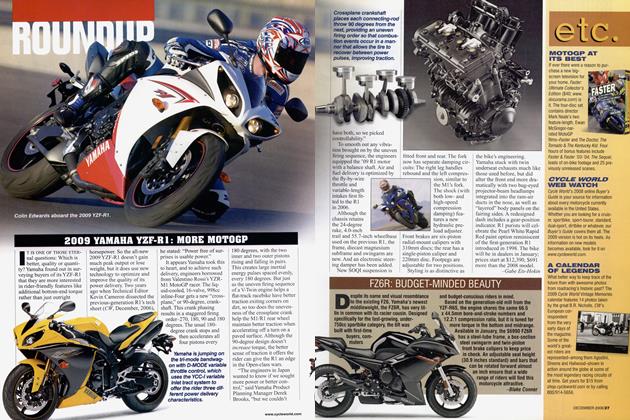

Roundup

Roundup2009 Yamaha Yzf-R1: More Motogp

December 2008 By Gabe Ets-Hokin -

Roundup

RoundupFz6r: Budget-Minded Beauty

December 2008 By Blake Conner