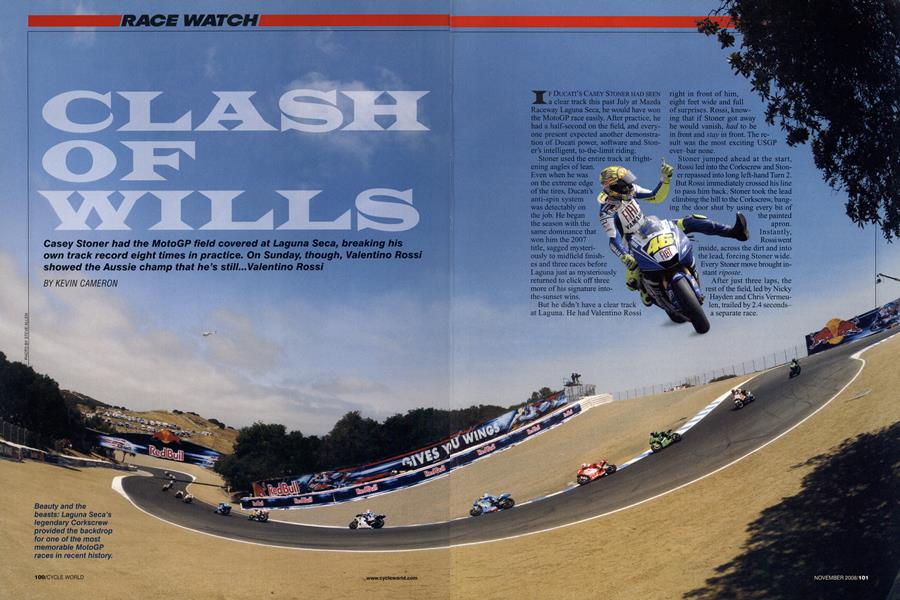

CLASH OF WILLS

RACE WATCH

Casey Stoner had the MotoGP field covered at Laguna Seca, breaking his own track record eight times in practice, On Sunday, though, Valentino Rossi showed the Aussie champ that he's still...Valentino Rossi

KEVIN CAMERON

IF DUCATI'S CASEY STONER HAD SEEN a clear track this past July at Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca, he would have won the MotoGP race easily. After practice, he had a half-second on the field, and everyone present expected another demonstration of Ducati power, software and Stoner's intelligent, to-the-limit riding.

Stoner used the entire track at frightening angles of lean. Even when he was on the extreme edge of the tires, Ducati’s anti-spin system 41?®^-=» *^8*5 was detectably on the job. He began , the season with the ^ VL ^ same dominance that f" won him the 2007 Ik " title, sagged mysteri' ously to midfield finishes and three races before Laguna just as mysteriously jSj returned to click off three more of his signature into\J5H the-sunset wins. ‘ But he didn’t have a clear track at Laguna. He had Valentino Rossi

right in front of him, eight feet wide and full of surprises. Rossi, know ing that if Stoner got away he would vanish, had to be in front and stay in front. The re suit was the most exciting USGP ever-bar none.

¶ I Stoner jumped ahead at the start, Rossi led into the Corkscrew and Ston er repassed into long left-hand Turn 2. But Rossi immediately crossed his line to pass him back. Stoner took the lead climbing the hill to the Corkscrew, bang ing the door shut by using every bit of the painted apron. Instantly, Rossi went inside, across the dirt and into the lead, forcing Stoner wide. .4 Every Stoner move brought in stant riposte.

Afterlust three laps, The rest of the field, led by Nicky Hayden and Chris Vermeu len, trailed by 2.4 secondsa separate race.

Stoner’s strongest play was to make a hard drive off Turn 11 onto the pit straight where his Ducati’s acceleration had room to out-drag Rossi’s Yamaha. With positions reversed, Stoner could choose his line through Turn 2, then clear off.

Rossi let Stoner choose nothing. On lap 13, Stoner did lead past start/finish. But into 2, Rossi pushed Stoner wide-onto pavement where his anti-spin/wheelie settings were wrong. Advantage Rossi, as Stoner took a 0.65-second slap for his trouble. Ducati power and Stoner’s deartrack mastery zeroed this mistake in three laps, and they were back nose-to-tail.

I thought of Henry Kissinger’s advice on Cold War foreign policy: Let the opponent think you’re crazy, that you might do anything, and he won’t provoke you!

Stoner kept close but didn’t provoke for nine laps. Rossi pulled away down the Corkscrew, but Stoner closed in down the hill. Flying formation is difficult as you must throttle up and down to keep position. Does Ducati’s wonderful software work just as well when the rider sends such confusing signals?

Maybe not. Loris Capirossi-formerly with Ducati, now riding a Suzuki-failed to win as many races on the 2007 800cc Ducati as he had on the previous 990 because he could not make himself do what the youngsters do naturally: just pin the throttle and let the computer do the rest. He worked the throttle as he always had on bucking 500cc two-strokes. On the 800, that method confused the system, making him slow.

Whatever the reason, as Rossi and Stoner braked and began to turn into T11 on lap 23, Stoner got in a little hot. Was

he preparing a fresh pass? Did Rossi himself carry extra speed this lap, just to make Stoner’s life more interesting? Stoner’s back tire lifted and brake weave beganno basis for corner insertion. He eased up on the lever and his tire settled. But now he ran wide with extra speed. He was in the dirt, the front tucked and he was down. He was soon up and going again, accelerating hard and still in second place, but that little mistake cost him 14 seconds-and the race.

In the post-race press briefing, Stoner complained of what he called Rossi’s “aggressive riding,” saying that although only 22 years old, he has years of experience and had never run into anything comparable. This is what any rider good enough to get close to Rossi always discovers: that Rossi can set problems faster

than his opponent can solve them. Ask Max Biaggi. Ask Sete Gibernau. Rossi stretched those capable men until they broke. Rossi’s public persona is the funloving imp. His competitiveness is private—until you get close.

Racers race. It’s not a pure contest of lap time in which the lesser rider waves the greater one on. When Gary Nixon was racing, the late Cal Rayborn was the supreme stylist, faster than any rival on a clear track. But when Nixon got close, showing him a wheel or coming up the inside to force Rayborn off-line, it became a double problem, a race against a track and against a man. With Nixon in his face, Rayborn became mortal.

Stoner was fast from the first lap of practice, using the whole track plus the painted edges, his bike juddering, bark-

ing and weaving. Like Mick Doohan before him, he was making every hard-ridden lap teach him something. By contrast, Rossi was smooth, conservative, even calm. The Ducati’s sound was harsh-high and irregular-that of the Yamaha deeper-toned, resonant like a three-cylinders.

I thought to myself, “Rossi is melody, Stoner is jazz.” Between Turns 3 and 4, everyone but Stoner was finishing T3 just short of the paint, going straight to T4, then launching from inside the paint. Stoner nearly made one turn of the two, sailing out onto the shiny stuff, right to the edge of the dirt and beginning his turn from there. Photographs show him braking hard on the paint, lifting the back wheel, then countersteering hard on those slick-looking blue-and-white stripes as he initiated Turn 4. Confidence! He blitzed practice, qualifying (a full second-anda-half faster than a year ago!) and Sunday warm-up. No one was in his class.

Michelin riders were desperate despite

Hayden’s second place in Friday’s afternoon practice, for available tires were too hard for the low air temperature of 61 degrees. Last year, Michelins gave up in the heat. Now the French company had over-compensated. Colin Edwards said of his tire temperatures, “We need 260-275 degrees but the closest we can get is 240.”

Low pressures to make heat from flexure just upset handling. Might higher pressures overwork a smaller footprint enough to heat up? No dice. Hayden's crew in desperation even tried rain intermediates. With the current tire rules limiting the number of tires per rider, a gamble is made on Sunday temperature, and a spread of rubber and construction hardnesses is supplied for it. Michelin lost-its technology has a narrow operating range. Bridgestone, half a world away, developed wider-range product because it couldn’t make tires overnight as Michelin did before rules forbade it.

Against this background, Bridgestone achieved a top-three sweep at LagunaRossi, Stoner and Vermeulen, with the top Michelin finisher, Andrea Dovizioso on a satellite-team Honda, in fourth.

Consider Honda’s apparent disarray. How does the “factory guy,” Hayden,

running the new pneumatic-valve engine, finish fifth behind a satellite Honda on the same tires? Okay, favored-runner Dani Pedrosa went home with an unraceable hand injury, and there was the Michelin Problem.

Pete Benson, Hayden’s engineer, said the valvespring engine (which Pedrosa continues to use) is stronger on the bottom but fades on top, while Hayden prefers the power of the pneumatic version. Meanwhile, Yamaha has made a smooth transition to pneumatic springs and Suzuki continues to develop its system-now in its third year of service. Honda budget-pinch whisperings have been audible since 2005, but how would we know?

Hayden in fifth and Edwards (having his best MotoGP season yet and has signed for another year) back in lowly 14th were victims of the cold Michelins syndrome. What about the other Americans-wildcards Ben Spies on a Suzuki and Jamie Hacking on a Kawasaki (both, by the way, on Bridgestones)? Spies was

11th through three practices, qualifying 13th and then raced to a solid eighth. In AMA Superbike, he qualified first and then an hour after the MotoGP race finished a distant second to Mat Mladin. Tired? Nope. He was carted off for an appendectomy! Hacking looked good in the first practice, but others advanced faster than he did. He fought back in the race, finishing 11th. John Hopkins, for whom Hacking was a fill-in, was present but sidelined by previous injury.

Speaking of AMA Pro Racing, its longawaited 2009 AMA/DMG rules were issued Saturday night. Extra! Extra! Revolution canceled! We'd expected fireworks between DMG’s Roger Edmondson and

the manufacturers, much as the courtly Bill France Sr. eased the automakers out of NASCAR many years ago. No! The classes and rules announced are amazingly similar to those already in place. Is true that Honda has wanted out of the series for 12 months and may use this “revolution” as pretext to leave now? Could there be a broader Honda need to economize in a general racing pull-out? Stay tuned, there’s sure to be more.

Edwards told us why this seasonLaguna excepted-has been his best in MotoGP, now that he’s separate from Rossi, on a Yamaha satellite team.

“During the Jerez and Malaysia tests, I got to test all the new parts, and pretty much pick what I liked-what / thought matched in terms of stiffness,” he said. “Everything’s been so hard and stiff. It’s all been built for Valentino over the years; he grew up on mini-motos with no suspension, 125s-he likes that. I was a Superbike guy. I like things to move around get a bit of feel. It seems to have worked out. This season, we’ve pretty much been there. This is the first track where we’re out of our element. We’re trying all kinds of stuff that we’ve never tried.”

Throughout practice, we could see many riders on soft springs-revealed by near-zero ground clearance when cornering compressed their suspension. Softer springs improve grip over Laguna’s notorious bumps and ripples, pavement features created by heavy racing cars. Stoner noted that with such softer springs, “Every time I release the brake, I keep running wide.” A concern this year has been “bucking,” and we could see this as he finished corners. The bike, as he put it, wanted to “shake and shudder all over the place.” A change of tire construction improved this, so he could “get on the

gas without the thing wanting to buck.”

With much fanfare, Rossi has switched from Michelin to Bridgestone tires, yet success was not immediate. His engineer, Jeremy Burgess, recounts that at the first GP of the season, Qatar, “There were three Yamahas on the front row, but Valentino’s wasn’t one of them. Casey won the race on exactly the same tire we were using. We got through to lead the race but we finished fifth. We had every piece therethe bike was capable of the speed, the rider was capable of leading and the tire that we had on won the race. All we had to do was put those pieces in their proper places.

“It was clear to us that we were losing the grip on the tire on the entry to corners-he had to use very tight lines,” Burgess added. “We needed to put more pressure on the (rear) tire to stop it dragging into the corner.”

MotoGP Michelins are currently very low-pressure, soft-construction tires that likely give a larger footprint and more grip under the light load of deceleration than do the stiffer-constructed Bridgestones. Burgess was referring to the tire’s role in handling a large four-stroke’s natural engine braking. If there isn’t grip enough to keep the tire turning the engine, it drags, overheats and loses grip. Restoring this balance therefore required tucking the rear tire farther under the bike, then regaining original wheelbase by moving the steering axis forward-

changes spotted as they happened earlier this season by eagle-eyed MotoGP tech commentator Neil Spalding.

It was a rare privilege to join Yamaha’s racing chief, Masao Furusawa, for lunch. He made clear by silence that pneumatic valve questions would not be answered, but noted that direct cylinder fuel-injection had been studied. This two-strokelike fuel system admits only pure air to the cylinders, then injects fuel after valve closure, as on Cadillac’s new CTS V-Six. With no fuel vapor taking up room in the inlet system, more air is taken in, boosting torque. Fuel loss to intake blow-back or on overlap is stopped. Although attractive for its power and economy, DFI is currently workable only to 15,000 rpm and may prove too expensive for production use (the new Porsche 911 engine also uses DFI).

Furusawa gave some insight into his engineering style, saying that he and Valentino are “very positive.” Assigned to solve snowmobile suspension problems, he made a complete redesign. He did the same with Yamaha’s YZR-M1, starting over with a suite of new concepts. Rossi clearly has confidence in this man; on Friday, Furusawa signed him for another two years of racing.

Rossi spoke of the higher speeds and reduced margin of safety in current racing. “But why?” he asked. “In the past, we had to open from the edge (of the tire), wait a bit, put more tire on the ground, use the acceleration, control with the throttle the wheelie, so you are able to arrive at 100 percent throttle 70 meters after the corner. Now? Full throttle, and all the electronics manage the power and the wheelie, so you arrive at the next corner much faster.

“Before, the fastest rider had a great relationship with the throttle,” he continued. “Like love with the throttle. We are sensitive to open the throttle, so we are fast. Now.. .is a computer.”

Rossi went on to link electronics with less-exciting racing. Burgess revealed an opposite view: “He’s one of the outgoing generation (of riders) who would like to see things return to the status quo. And he would win. Keeping things the same all the time is not how the future is going to be.”

Rossi also acknowledged electronic progress. “This year,” he said, “the bike has improved a lot, especially in the engine and electronics. Last year, it was a lot more difficult to ride.”

Unless Yamaha rapidly achieves performance and software equality with Ducati, the next races could easily return to “Stoner-mode.” Yet for the moment, the claims that “electronic racing” is boredom are refuted by the intense Laguna contest. Of course, it helped that Rossi and Burgess “made a small setup

change” between the Sunday morning warm-up and the race itself.

Production bikes continue the electronic revolution, as they must, but can racing’s fundamentalists ban electronics and head for 1950? We hope for more fabulous contests between Stoner and Rossi, but the treasure consumed by MotoGP development, plus visible grid shrinkage, suggests this golden age can’t last. Many believe that some cheaper production basis must one day replace it. But World Superbike already has that role. High fuel prices and “green” expectations will change the fundamental nature of motorcycles, both production and racing. Chinese and Indian producers grow in power-and ambition. My predictive software locks up on all these question marks, so I’ll have to see the future one day at a time. Brace yourselves for change. □

"For an interview with Valentino Rossi from the USGP~ visit www.cycleworld.com

View Full Issue

View Full Issue