SERVICE

PAUL DEAN

Slip-slidin' away

Q I'm confused about slipper clutches. How are they different from standard clutches and why are they needed? The articles I have read said they help prevent wheel hop while downshifting quickly. I must be missing something, but if the clutch is disengaged, which means the engine is disconnected from the driveline, why would there be "wheel hop"? How do these clutches affect engine braking? Can you release the clutch in a low gear while entering a turn and open the throttle, only to find that power is not transferred to the rear wheel until the engine and driveline are at the same speed? Does this make the engine rev, basically freewheeling, until the clutch engages? I know I have asked a lot of questions here, but I want to understand these clutches and can't find many articles that explain them. Kevin Roach Ilion, New York

A You're right: You are confused. So let's unravel the mysteries. Based on the wording of your ques tion, it would seem that you subscribe to the "all at once" method of downshift ing in which you disengage the clutch, then click down through all the requisite gears before re-engaging it when you either come to a stop or continue under power. With that style of downshifting, a slipper clutch is indeed unnecessary because the clutch remains disengaged throughout the entire process. But that's not how most roadracers and fast sportbike riders simultaneously brake and downshift. As they approach a corner hard on the brakes, they shift down sequentially, re-engaging the clutch after each shift to take advantage of engine braking and end up in the correct gear when it's time to accelerate out of the turn. But due to the enormous power of the front brake, the tenacious grip of the front tire and the forward weight transfer

that occurs during hard braking, the rear end gets very light, and the additional braking caused by engine compression after each downshift can make the lightly weighted rear wheel begin hopping. This is especially so if the rider doesn't rev the engine quite high enough between downshifts, which not only increases the amount of engine braking but also causes that braking force to arrive at the rear wheel very abruptly. To help combat this compression-in duced wheel hop, slipper clutches are built with simplistic internal mecha nisms, usually just little ramps of one kind or another, that relieve some of the spring pressure on the pressure plate-and the operative words here are "some of the pressure," not "all of the pressure." The ramps let the clutch slip just enough to prevent the rear wheel from hopping but not enough to disengage the engine entirely from the driveline. They even are somewhat self-adjusting in that the

greater the amount of engine braking, the more slippage they provide. You often can feel the slippage if you have your fingers on the clutch lever, which will move ever so slightly closer to the grip when the ramps push on the pressure plate. Plus, slipper clutches are one-way devices that only act when the rear wheel is driving the engine, not vice versa. So if you open the throttle in the middle of a hard-braking turn, the ramps immediately disengage and the bike will begin accelerating just as it would with a conventional clutch.

I hope this explanation clears up at least some of your confusion about slipper clutches.

His cupping runneth over

Q I hope you can explain a wear problem I'm having with the front tire on my `84 Honda CB700SC Nighthawk. The 16-inch wheel size gives few options in the aftermarket tire supply, so when the original-equipment Dunlops wore out, I replaced them with Avon Roadrunners. The Avons improved the performance but the front wore unevenly to produce a series of high and low spots on the center of the tread. I replaced the Avons with a pair of Bridgestone Battlax BT-45s, and the performance in both wet and dry was again improved, but the front tire has worn in the same way. On either side of the central groove, the tire developed low spots between the tread's V blocks and high spots on the V blocks. This wear pattern results in a shake in the handlebar as the wheel rotates. This shake is not noticeable under normal riding conditions (holding the grips tightly) but occurs when the grips are very gently held.

very

I have spoken about this wear pattern to some of my long-term biking friends and mechanics, and other than “normal wear,” I don’t get any good explanations. Everything appears straight, the bolts are all correctly torqued and the bike has never been in an accident. Any explanation you can provide and suggestions for corrective action, if any, would be appreciated.

Roger Mann Dutton, Virginia

A This front-tire wear patterncalled "cupping"-is very common, and not just on motorcycles; cars also suffer the same kind of front-tire wear.

This is why tire manufacturers recommend rotating the tires on automobiles at regular intervals-a practice that is impossible on motorcycles, virtually all of which use two different tire sizes and types. The condition occurs more often with some tires than others, even more so with some bikes than others, and even more yet with the combination of certain tires on certain bikes. I don’t recall if the Nighthawk is a particular offender, but I’m not surprised to learn that you are having such a problem.

Simply put, cupping is caused by flexing and squirming of the tread surface as the tire is subjected to the considerable forces of cornering and braking. It’s a difficult problem to overcome-for tire manufacturers as well as for consumers-because there are so many variables and compromises. Every model of motorcycle has either different front-end geometry or different overall weight or different weight distribution or a different center of gravity or all of the above, yet those are some of the main factors that

dictate how a bike feels and handles. Consequently, a tire manufacturer can’t design a single front tire that is ideally suited to all motorcycles.

In some cases, building a tire that minimizes cupping would result in one that provided undesirable-maybe even unacceptable-handling characteristics.

I’ve talked to several tire engineers about this problem, and they all agree that underinflation is the most common cause. Makes sense, since cupping is caused by the flexing of the tire, and underinflation results in more flex than usual. They suggest keeping the front tire right at, or even a pound or two above, the recommended psi. That isn’t likely to eliminate cupping altogeth er, but it should reduce it enough to extend the useful life of the front tire.

Gas hogs

A few of my friends and I have issues with the gas-mileage figures your magazine publishes in its road tests. We own some of the very same models you have tested during the past couple of years, and we always get better mileage than what is reported in the tests. We never get mileage that is as low as your lowest figures, and we frequently exceed your best figures. Why is this?

Dennis Taylor New Castle, Pennsylvania

A There are

numerous probable reasons for these discrepancies, and the most likely is a dif-

Feedback Loop

In response to Tim Allen's complaint about bike tires costing so much compared to car tires ("Rubber match," June issue), I have to disagree. I am an automotive technician from Canada, and I have priced tires for "luxury-performance" cars (Lexus, lnfiniti, etc.) that have far exceeded the thousand-dollar mark! The performance and mileage most motorcycle tires offer go beyond what those luxury performance tires provided. On one particular car, the OEM tires got a whopping 12,000 kilometers (7500 miles) before they were worn down to their wear bars, with some extra wear on the edges, probably due to slight underinflation. It sure wasn't from hard cornering; the car in question was an under-used golf-bag tote. Chris August Posted on America Online

ference in riding conditions and objectives. Our mileage numbers reflect the gamut of our testing regimen-the exception being time spent on roadrace tracks, where we fuel the bikes from gas cans and thus have no accurate measure of their consump tion. But everywhere else, we keep close track of the mileage. This usually includes quarter-mile and top-speed testing for all motorcycles, as well as many miles of full throttle, high-rpm, shifi-at-redline riding on performance machines. Readers expect us to report on the entire envelope of a bike's performance potential, and that requires us to log more of those kinds of miles than most other riders might experience. Given those factors, we fully expect that our read ers will often get better mileage than we do.

Dyno definitions

Q I have a question regarding Dynojet dynamometers, and I am asking this of you because on many occasions, tests and stories in Cycle World have men tioned that the magazine owns one. I know how other types of dynos work: They use a brake of some kind to hold an engine at specific rpm levels and measure the torque and horsepower produced at those rpm. But I don't understand how a Dynojet dyno measures anything. You just strap a bike onto it with the rear wheel on a big roller, shift into one of the higher gears, rev the engine from low rpm to maximum rpm and the dyno spits out horsepower and torque numbers. Could you please enlighten me-and perhaps many of your other read ers who also do not understand how these machines work? Paul R. Shoemaker Tulsa, Oklahoma

A It's pretty simple, actually. Key to the dyno's operation is Dynojet's proprietary computer software that 1) is programmed to know the force required

to make the 400-pound rear-wheel roller I; from any rpm to any other rpm;

2) incorporates avery accurate clock timer; 3) takes hundreds of roller-rpm

samples every second; and 4) includes basic calculating capabilities. The dyno also is equipped with a speed sensor that measures roller rpm, along with a pickup cable that connects to a sparkplug wire or an ignition primary wire to keep track of the test bike’s engine rpm. By comparing roller speed to engine speed, the dyno calculates the overall ratio of the gear in which the run is taking place.

When you rev a bike up through its rpm range on the Dynojet, the computer knows that the roller was accelerated from one rpm to another, precisely how long that acceleration took, and the effective distance the roller was moved. The software then calculates how much “work” took place (work = force x distance) and how much “power” was generated (power = work time) as a result. Horsepower is a specific measure of work done over a period of time, so the computer instantly formulates the horsepower output at any of the thousands of sampling points between the start and finish of the run. Once it knows the horsepower, it uses simple math to calculate the amount of torque that was produced (torque = hp x 5252 -Fipm) at those same points.

Because of the way in which it measures power, this type of dyno is often referred to as an “inertial dynamometer” or an “accelerometer.” But for the past several years, Dynojet has also been offering a model that incorporates an eddy-current (electrical) brake so it can be run either as an accelerometer or as a “steady-state” dyno like the type you described. The inertial type is less expensive, which makes it popular for bike repair shops or smaller motorcycle dealers to use as tuning aids and a safer method of road-testing customer bikes. But for R&D work and serious engine builders, steady-state dynos provide more-meaningful information. □

Got a mechanical or technical problem with your beloved ride? Can’t seem to find workable solutions in your area? Or are you eager to learn about a certain aspect of motorcycle design and technology? Maybe we can help.

If you think we can, either: 1) Mail a written inquiry, along with your full name, address and phone number, to Cycle World Service,

1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach, CA 92663; 2) fax it to Paul Dean at 949/631 -0651; 3) e-mail it to CW1Dean@aol.com; or 4) log onto www.cycleworld.com, click on the “Contact Us” button, select “CW Service” and enter your question. Don’t write a 10page essay, but if you’re looking for help in solving a problem, do include enough information to permit a reasonable diagnosis. And please understand that due to the enormous volume of inquiries we receive, we cannot guarantee a reply to every question.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

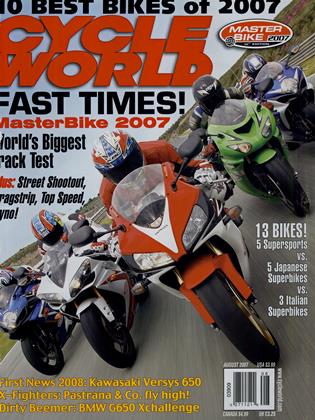

Up FrontTen Rest, 2007

August 2007 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsToo Much Bike, Not Enough Road

August 2007 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTales of the Testastretta

August 2007 By Kevin Cameron -

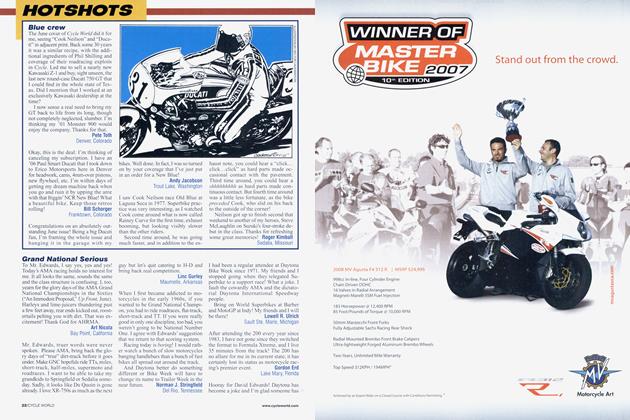

Hotshots

HotshotsHotshots

August 2007 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Tailpipe Chronicles

August 2007 By Paul Dean -

Roundup

RoundupCrocker Shocker

August 2007 By David Edwards