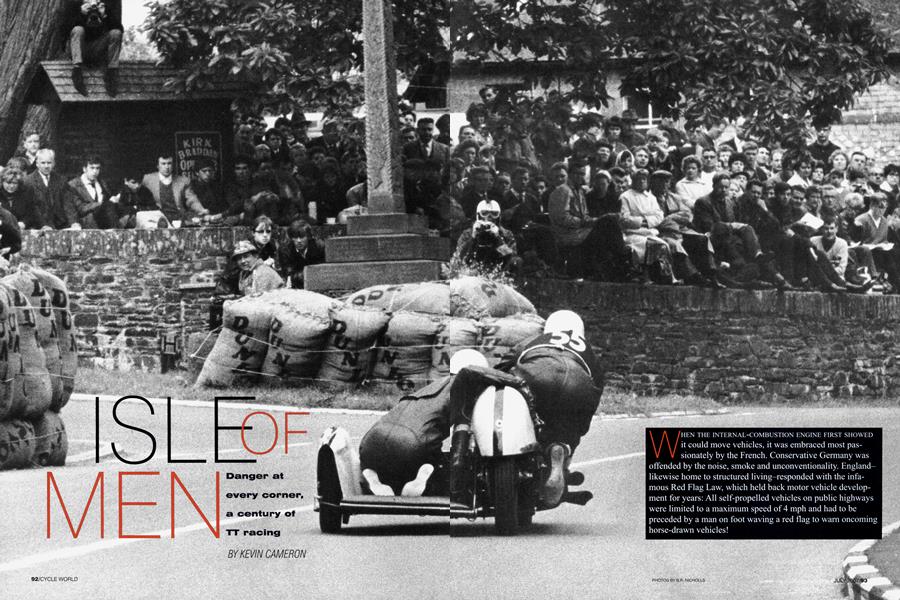

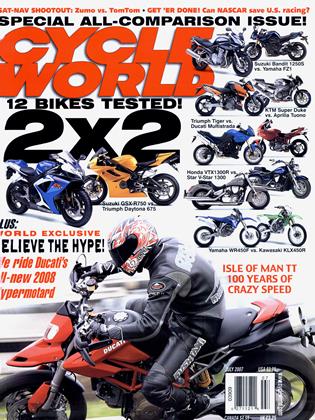

ISLE OF MEN

KEVIN CAMERON

Danger at every corner, a century of TT racing

WHEN THE INTERNAL-COMBUSTION ENGINE FIRST SHOWED it could move vehicles, it was embraced most passionately by the French. Conservative Germany was offended by the noise, smoke and unconventionality. England-likewise home to structured living-responded with the infamous Red Flag Law, which held back motor vehicle development for years: All self-propelled vehicles on public highways were limited to a maximum speed of 4 mph and had to be preceded by a man on foot waving a red flag to warn oncoming horse-drawn vehicles!

France and Spain hosted the infamous Paris-Madrid roadrace in which accidents took a hefty toll. No such disruptions would be permitted in England, where no form of racing on public roads was permitted. This brought into existence England’s two great classic racing venues: The Isle of Man TT, about to celebrate its 100th year, and the banked cement speedway at Brooklands. The Isle of Man, out in the Irish Sea and administered separately from England, could make its own laws. Brooklands was a private institution.

Racing in 1907 existed for reasons entirely different from those that drive it today. It was heavily supported by budding manufacturers as a means of proving to a curious public the durability of their machines. In 1911 the TT rules were changed to outlaw pedaling by the riders, as a way to encourage the development of variable-ratio drives. An Indian won the premier Senior event at a 47-mph race average. If this sounds pitifully slow, remember that the roads were rough-and unpaved.

Rapid development of materials and design was stimulated by the popularity of the TT, where success in the between-the-wars years could treble sales overnight. The coming of the worldwide Great Depression in 1929 put many makes out of business, but strong TT performers like Velocette and Norton found the means to continue development. A great deal was learned about cooling, fuels and how to make critical parts reliable. Just before WWII, government-backed machines from Germany and Italy excelled in the TT, but the battle between British

Singles and Continental multi-cylinder machines would be postponed as hostilities began in September, 1939.

When the FIM reconstituted the series in 1949, the TT became a part of the new European Grand Prix calendar. In 1950, the design of the twin-loop “Featherbed” chassis for Norton’s classic Manx 350 and 500 Singles gave those machines fresh agility.

Italian and German designs, shorn of their prewar superchargers by the new GP formula, were no longer able to win on pure speed. Racing had become the “scratcher’s game” of ever-faster cornering, braking and accelerating that it remains to this day.

As postwar rebuilding continued, new small cars entered production, taking from motorcycles much of their transportation appeal-and tightening bike-makers’ budgets. British and German teams left the GPs after 1954. Italian teams hung on three years longer but the first postwar Golden Age then ended.

MV Agusta, its income derived from helicopters, continued racing.

Honda, knowing the advertising power of the TT, brought a team of 125s to the Isle of Man in 1959. Three years later, the Japanese

harvest of world championships was well begun as 50, 125, 250 and 350cc titles would henceforth stand to the credit of Honda, Yamaha and Suzuki.

Times were changing. The 500cc class, formerly paramount, now became a ho-hum affair to be won by

a technologically backward Italian transverse-Four, followed home by a deep-toned pack of British Singles. The new center of attention was the 250cc class, in which Japanese factory bikes of two, four or six cylinders made “lightweight racing” the fastest class on the island. Recordings made at the TT during this second Golden Age of roadracing delight the ear with the ascending overtones of megaphone exhausts. Incredible and dramatic contests were fought out over the long TT laps.

The TT races had always presented unusual risks, for the events took place on public roads closed for the very festive and well-attended occasion. Fifty miles per hour between hedgerows or stone walls was impressive. A hundred and fifty raised the ante to an even higher level, such that a rider’s kinetic energy became 10 times what it had been in the early days. Have a look at the camera-on-bike footage of a modern TT lap and you will indeed wonder, “What men or gods are these?” The result has been a worrying attrition of riders injured and killed-sometimes as many as five dead in a

single TT week.

Meanwhile, the nature of racing itself had changed.

The old concept of proving machinery to a skeptical public over public roads often produced margins of victory measured in minutes. The new racing of the 1960s had become a closely fought, elbow-toelbow affair that was in itself spectacular, taking place on specially built closed circuits. Some riders began to view the TT as unnecessarily dangerous. No less a giant of the sport than Giacomo Agostini declined further participation, and the TT was eventually stricken from the Grand Prix calendar. Factory teams, by now paying high salaries to riders and investing untold millions in machine development, shrank from the negative marketing power of death.

Since that time there have been many exciting TT races, but they have in large part been contested either by TT specialists or by those who continue to see the island event as a supreme and worthwhile test of riders and machines. Some of the most revered TT heroes, long regarded as nearly immortal by reason of their impressive knowledge of the 37-mile circuit, have been killed while racing at the TT or on similar public-road events.

The choice belongs to the rider-whether to drink deep of the huge tradition and challenge and to accept the danger, or to leave the TT to history and to others. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue