VIEW FROM PIT WALL

Riders, racing and me

RACE WATCH

KEVIN CAMERON

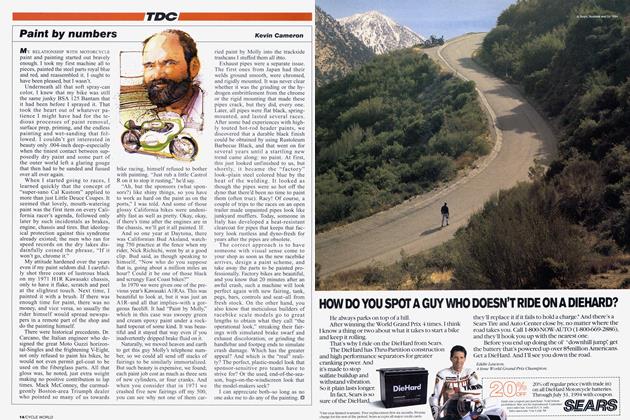

MY FRIEND AND FORMER RIDER, Cliff Carr, has died at age 62 of liver failure. When I took my Kawasaki H1 -R to Daytona in 1970,I happened to meet future Cycle Editor Phil Schilling and Cliff, who had come to the U.S. to pick up a bike. Months later, with crashed machines to fix and nobody but myself to blame for sending amateur riders into a Pro class, I cadged Cliff’s English address from Schilling and wrote to ask if he’d like to race in the AMA nationals in 1971. When Cliff’s answer was yes, everything was changed.

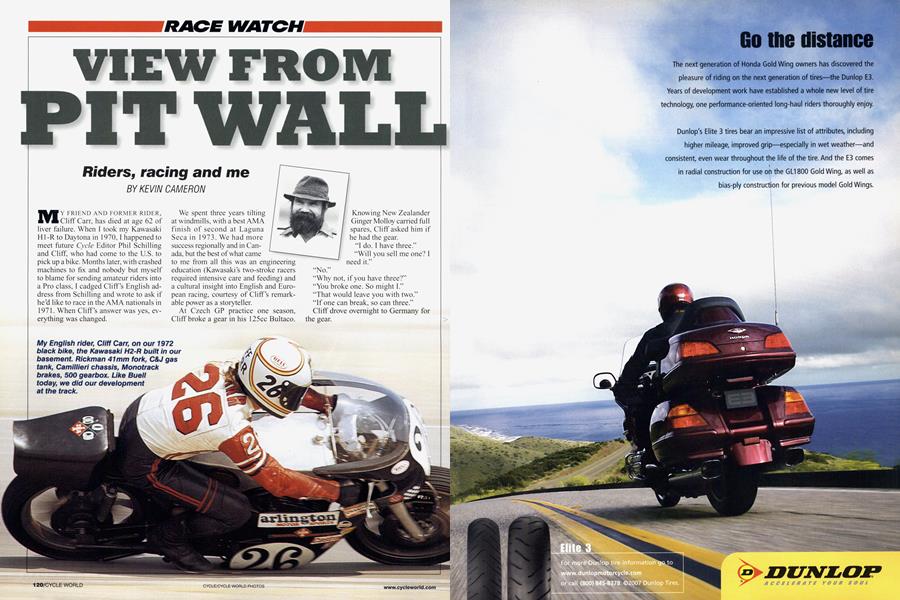

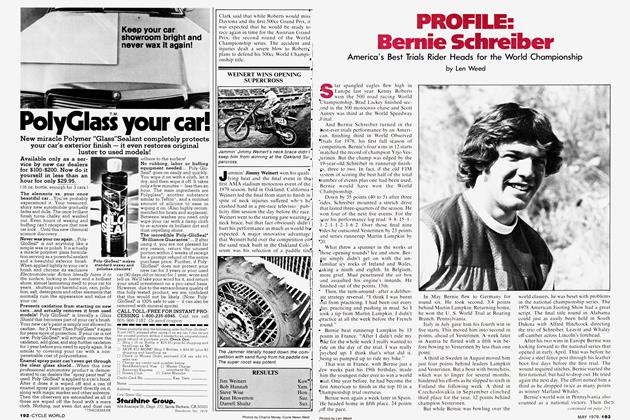

My English rider, Cliff Carr, on our 1972 black bike, the Kawasaki H2-R built in our basement. Rickman 41mm fork, C&J gas tank, Camillieri chassis, Monotrack brakes, 500 gearbox. Like Buell today, we did our development at the track.

We spent three years tilting at windmills, with a best AMA finish of second at Laguna Seca in 1973. We had more success regionally and in Canada, but the best of what came

to me from all this was an engineering education (Kawasaki’s two-stroke racers required intensive care and feeding) and a cultural insight into English and European racing, courtesy of Cliff’s remarkable power as a storyteller.

At Czech GP practice one season, Cliff broke a gear in his 125cc Bultaco.

Knowing New Zealander Ginger Molloy carried full spares, Cliff asked him if he had the gear.

“I do. I have three.” “Will you sell me one? 1 need it.”

“No.”

“Why not, if you have three?”

“You broke one. So might I.”

“That would leave you with two.”

“If one can break, so can three.”

Cliff drove overnight to Germany for the gear.

Not only Ginger but all the characters of British and European roadracing were given color and dimension in Cliff’s evocative storytelling.

He described an Italian GP in which Giacomo Agostini was leading the 500cc class. Italian families were picnicking all over the hills surrounding the course, and wonderful food and drink were filling all participants. Then Ago’s MV developed a misfire. Lap by lap, Mike Hailwood on the Honda advanced and finally passed for the lead.

“All the families began packing up their food and heading for the car park-if an Italian wasn’t to win, they refused to see it,” Cliff said. “But as their trek was only half completed. Ago’s MV cleared out and ran again, so that he shortly re-took the lead. All the families turned around, found their former places on the hills, spread their red-checked tablecloths, set out lovely food and resumed their picnics.”

At a hot regional race at Nelson Ledges, a Bultaco runner had pitted just behind us, on the grass. As we struggled with our overheating ignition electronics, the Bultaco fell over.

“It wanted a rest,” said Cliff, without looking up from his work.

In 1966, a friend had taken his 250cc Yamaha TD1-B to Europe and was disappointed to find that GP racing, which

we had all admired from afar because of the Honda/Suzuki/Yamaha factory battles, was otherwise pretty small-time. Top privateers pulled little caravans (called “honeymoon trailers” in the States) behind underpowered vans. Others could be found in tents or sleeping rough on the ground.

What a contrast with today, when a long row of more than 100 highly polished, beautifully painted tractor-trailers is backed in against the trackside garage building at any GP. Across from the high, blunt noses of the tractors is the row of complicated “transformer robot’’ hospitality suites, which fold out from (some-

times) multiple 40-footers. Each has a restaurant and a bar, with conference rooms. Between these is the crowded Grand Avenue, and behind the hospitalities are, first, the major accessory suppliers and, finally, the palatial motorhomes of the riders.

When I did half a season in Europe with Rich Schlachter in 1981, U.S. rid-

ers had just begun to tempt the paddock away from its traditional caravans with their mile-long motorhomes. Grassy or even forested paddocks had given way to paved plazas, dotted with power and water pylons to supply the needs of racers and staff. Yet I sat in a tiny caravan in Italy and had this education from an Italian racer.

“You are, perhaps, impressed with all

the money in this paddock? The transporters and the motorhomes? The factory motorcycles?”

“Yes, I must admit that I am. We have nothing like this at home.”

“Yet I must tell you that even the most rich of all of these will leave this paddock at the end of the weekend with less money than he had when he arrived.”

Almost 10 years before, I had thought it noteworthy at the Imola 200 that Erik Offenstadt’s large van had a rear-facing spotlight to make outdoor service possible at night. Garages? No, teams were issued lockups that were tin garden toolsheds that anyone with a can opener could enter at will. As Cliff and I soldered a wire connection with a roaring

borrowed tinsmith’s blowtorch, the Carabinieri helicopter came too low and blew down the press tent. Cliff and I later stood in the dusky paddock, talking with Paul Smart, next to Ducati’s famous “glass van.”

“They tell me this thing (the new 750 Twin) goes to 9750 rpm. Is that even possible?” Paul asked the air. “And they

say in an emergency, it’s safe to 11,000V'’ Big stuff in those days, when a modified Manx Norton 500 Single was risking its crankpin at 7200.

Agostini led the race on a shaft-drive MV 750, but in one of those accidents that change the flow of history, the MV

stopped and Ducati took the event, 1-2, with Paul (“Small Parts”) the winner. Overnight, Ducati was catapulted out of obscurity and had to take themselves much more seriously.

Weeks later, Ducati sent Imola second-placeman Bruno Spaggiari and bike

Dunlop's famed "triangulars." The "knife-edge" fronts some riders prefer to this day descended from this pioneering design. Before slicks arrived in 1974, all race tires were all-weather.

to Mosport, near Toronto, Canada, to the 750 race there. Cliff and I had the pleasure of leaving him behind on that faster course. Kawasakis-even our homebuilt 750-always went well at Mosport. We had been, in Cliff’s words, “rubbish” at

Imola. Did the very experienced Spaggiari actually “tip over” (favorite phrase of Y von Duhamel’s factory Kawasaki mechanic and now AMA Supercross manager Steve Whitelock) at Moss’s Corner? Or did he choose the slowest, softest place

to preserve company honor?

Before the 1973 Dallas AMA National, Cliff Whitelock and I were concerned to discover that “piston, new type, better, also cheaper,” was developing cracks above its wristpin bosses.

“Can we still get last year’s pistons?” we asked the Kawasaki team technician, Mr. Kazuhito Yoshida.

“Hahh, not possible. New vendor.” Small right-angle mirrors saw a lot of use the rest of that season, charting the progress of the cracks, which began in about 50 miles. The official answer was pistonsmuch heavier pistons-with no machining in the critical area. And the failures began. When a multi-cylinder engine has a mishap in one cylinder, the other cylinders keep right on going. The result was a lot of parts ejected into the exhaust pipe of the failed cylinder-parts so badly beaten up that it was impossible to know if the rod had parted from the load of the heavier piston, or if the rod had torn the pin bosses out of the piston and then bent and hammered itself to death.

Cl iff got a Suzuki factory ride for 1974. He needed to make some money, but splitting that way was a kind of divorce for us-not a happy time. He described

himself and Smart choosing brake pads for the Daytona 200 by pressing their thumbnails into new pads stored loose in a big box in the Suzuki transporter. Anybody know what these pads are? Anybody ? Nope. Here, these look good. Cliff’s weren’t-his pads wore to the metal backing at 2A distance. He found himself unzipping his leathers from the neck as a crude airbrake. So much for the thumbnail test. I had a better year with California rider Jim Evans on the then-new Yamaha TZ750A. Jim was third (and first privateer) at both Talladega and Ontario.

As a late teenager, I was ignorant of racing’s drama until I arrived in a college town and began to read British magazines, what Cliff called “the comics.” In those hallowed pages, I learned that a “P. Read” had distinguished himself in an event called the Manx GP. I began riding on a distinctly newbie $140 BSA D1 Bantam, whose 4.95 horsepower at 4500 rpm were enough to overcome tire rolling resistance but not aero drag. Ten dollars of summer job money also bought me a copy of Ricardo's The High Speed Internal Combustion Engine.

American racing in the 1960s was splitting. The native part was dirt-based-men in flat-top haircuts on flat-head motorcycles, sideways at the fairgrounds. The new part was roadracing, coming from regional clubs and modeled on European sport. The Daytona 200 came in from the >

sand to the present Speedway in 1963, but traditionalists remained suspicious of pavement racing. In place of the steeltoed construction-worker boots of real men, pavement types wore “fruitboots.” One-piece leathers-as opposed to manly leather pants-and-jacket style-were equated with Danskins. Back then, the word “gay” still meant “having or showing a joyous mood,” but it would otherwise have found plenty of use in disparaging descriptions of roadracing and its dainty feet-on-the-pegs style.

Back and forth went the struggle, but the explosion of motorcycling’s popularity in the U.S. made roadracing impossible to ignore. Once British and Japanese 750s hit the market (1970-72), U.S. roadracing went big-time, drawing British and European riders in droves. The marketing problem was to separate this clean new sport from its naughty black-leather origins, and our AMA hit upon the device of colored leathers. Now the shoe was on the other foot as American racers in their new “suits of lights” became the butt of jokes for British traditionalists in their “tatty blacks.” Colored duct tape was now the savior of low-bucks riders, and makers of racing suits stocked all the colors of the rainbow.

U.S. 750 racing was so successful in 1972-76 that it and similar European events drew larger crowds than the GPs.

It was nearly adopted as a GP class, but returning European prosperity and new 500cc entries from Suzuki and Yamaha soon blew 500 GPs to comparable or greater size.

Tennis was once considered an effete country-club sport, but TV made big business of it. Somewhere along the way, Bernie Ecclestone saw motorcycle GP>

racing as a $20 bill, just lying on the ground. Anybody belong to this bill? When no one claimed it (GP racing was run “pour le sport" by older gents in blue blazers), he picked it up and demonstrated its major drawing power. GP racing became huge on TV, and that is what has enabled the present degree of spectacle.

GP classes were originally 125. 250, 350 and 500cc, but 50cc was added (later increased to 80) and in time 350 was dropped. For a while, sidecar was a hotbed of advanced technology as the machines became three-wheeled GP cars. When TV took over, sidecar was bumped; today, the three classes are MotoGP (now 800cc), 250 and 125. The very competitive smaller classes feed riders to MotoGP.

When Cliff Carr and I struggled with air-cooled two-strokes in the 1970s, U.S. importers’ teams traveled in box trucks and privateers, like ourselves, in vans. MotoGP packs its gear into shipping containers for the “away” events, and a contract 747 freighter airlifts it. When Cliff and I shipped our 1972 bike to England on a pallet, the airline presented it to us lying on its side, its fairing broken. Later, I made a crate that would accept a compact toolbox and some spares as well as the bike.

Crossing borders was once a special art, requiring smooth talk and controlled>

distribution of team T-shirts and hats. Most places, this worked. But when Cliff gave me and my K.R-750 a ride back to England in 1976, Her Majesty’s Inland Revenue accepted my documents but not his. In the 1960s, English racers had driven to Spain, bought new Bultaco TSS racers, then smeared dirt on them and brought them home as “used motorcycles.” This time, no dice. They questioned him for hours, even accompanying him to the bathroom as if he were a capital suspect. This concentrated his mind-he remembered a tiny legal clause. Englishmen who had resided abroad for six out of the previous 12 months were exempt from duties on certain articles-motorcycles included. Very good, sir. Sorry to have troubled you, sir.

At one border in 1981, Rich Schlachter and I were next in line behind the Honda transporter. We could see on their documents the valuation of their oval-piston NR500 V-Fours: $1 million each. That was 26 years ago, and it seemed like a lot. What did we know?

At Talladega in 1974, the factory Yamaha TZ750As wouldn’t go straight. Don Castro's bike flung his feet right off the pegs, and privateer Dave Smith sat whitefaced and shaking in a lawnchair after his practice. The groove for a little wire clip in the fork dampers hadn’t been cut deep enough, making the dampers inoperative. Kel Carruthers had the team bikes apart much of Saturday, discovering this. Later he would comment, “In the future, we'll have to put as much preparation into chassis as we now do into engines.”>

There’s an understatement.

Racing technology has become specialized. In 1971, Carruthers and the late Don Vesco assembled cranks, planned, cut and welded chassis alterations, and ported cylinders to win races. They were like the frontier family that could deliver a baby, raise a barn or plow the land. When Kel was elevated to manager of Yamaha’s 5()0cc GP team, he said, “We’re just partschangers now.” All the engineering came from the factories.

Today, this is even more true. As chassis setup took precedence over engine power, so now software is taking precedence over hardware. The motorcycle is just the means by which the unseen software is expressed. Change the software and the machine’s entire behavior changes. Every aspect of the operation is handled by specialists-the fuel-injection guy, the suspension guy, the data-pack guy. In some cases, this becomes a Tower of Babel, in which every specialist speaks his own separate language.

In 1997,1 realized that some 500cc GP teams now had more than one tractortrailer transporter. Now it has become the norm a necessity. Chefs in the hospitalities vie with one another to produce the most lavish meals. It has all become wonderfully professional-the very thing Steve Whitelock and I once fantasized aboutbut at the same time has lost some of the up-front personal character it once had. Cliff described 6 a.m. in a German paddock of the 1960s, when a 50cc runner shattered the silence by starting his tiddler and noisily warming it up. Cliff’s caravan mate sat straight upright out of sound sleep, a mad Carl Fogarty look in his eyes. Without a word he left the trailer, picked up a bucket of icy water and dashed it over the offender. No worries about media reaction or factory politics. Calm restored, sleep again possible.

Racing will always produce wonderful characters like these because even now it remains so far from the mainstream. The evolution of the spoil has just fixed it so that now we have to negotiate months in advance (what did you say your circulation was again?) to have 20 minutes of those wonderful characters’ increasingly sought-after and scheduled time. □