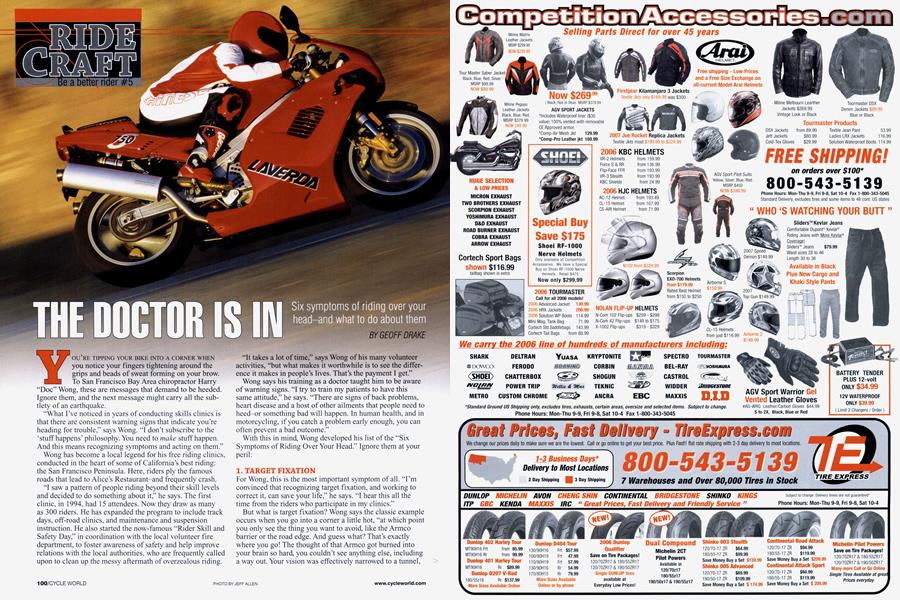

THE DOCTOR IS IN

Six symptoms of riding over your head-and what to do about them

GEOFF DRAKE

RIDE CRAFT Be a better rider #5

YOU’RE TIPPING YOUR BIKE INTO A CORNER WHEN you notice your fingers tightening around the grips and beads of sweat forming on your brow. To San Francisco Bay Area chiropractor Harry “Doc” Wong, these are messages that demand to be heeded. Ignore them, and the next message might carry all the subtlety of an earthquake.

“What I’ve noticed in years of conducting skills clinics is that there are consistent warning signs that indicate you’re heading for trouble,” says Wong. “I don’t subscribe to the ‘stuff happens’ philosophy. You need to make stuff happen. And this means recognizing symptoms and acting on them.” Wong has become a local legend for his free riding clinics, conducted in the heart of some of California’s best riding: the San Francisco Peninsula. Here, riders ply the famous roads that lead to Alice’s Restaurant-and frequently crash.

“I saw a pattern of people riding beyond their skill levels and decided to do something about it,” he says. The first clinic, in 1994, had 15 attendees. Now they draw as many as 300 riders. He has expanded the program to include track days, off-road clinics, and maintenance and suspension instruction. He also started the now-famous “Rider Skill and Safety Day,” in coordination with the local volunteer fire department, to foster awareness of safety and help improve relations with the local authorities, who are frequently called upon to clean up the messy aftermath of overzealous riding. “It takes a lot of time,” says Wong of his many volunteer activities, “but what makes it worthwhile is to see the difference it makes in people’s lives. That’s the payment I get.” Wong says his training as a doctor taught him to be aware of warning signs. “I try to train my patients to have this same attitude,” he says. “There are signs of back problems, heart disease and a host of other ailments that people need to heed-or something bad will happen. In human health, and in motorcycling, if you catch a problem early enough, you can often prevent a bad outcome.”

With this in mind, Wong developed his list of the “Six Symptoms of Riding Over Your Head.” Ignore them at your peril:

1. TARGET FIXATION

For Wong, this is the most important symptom of all. “I’m convinced that recognizing target fixation, and working to correct it, can save your life,” he says. “I hear this all the time from the riders who participate in my clinics.”

But what is target fixation? Wong says the classic example occurs when you go into a corner a little hot, “at which point you only see the thing you want to avoid, like the Armco barrier or the road edge. And guess what? That’s exactly where you go! The thought of that Armco got burned into your brain so hard, you couldn’t see anything else, including a way out. Your vision was effectively narrowed to a tunnel, and that object was the only thing in your universe at that moment.”

Target fixation is really a case of our senses working against us. “I’ve seen riders fixate on a spot off the road edge and ride straight there,” says Wong. “But in so many cases, if they had done nothing and just completed the corner normally, they would have been fine.”

Wong says the solution is simple: Force yourself to look through the corner. For some this may be counterintuitive. “You might think it’s more dangerous to look up the road than at the thing you want to avoid,” he says. “But at that moment, when you have a slight feeling of panic, you must literally ignore the target-fixation urge.”

Of course, there are no guarantees. “If you are really going in too hot, or have set up improperly for the corner, you might still fall down. But avoiding target fixation and looking up the road will at least give you a fighting chance. It’s always your best strategy.”

2. The Death Grip

Perhaps the most obvious of the Six Symptoms is gripping the handlebar too firmly. Typically this happens as you enter a turn, and it begins with tightness in the hands and fingers, then the arms and shoulders, and in extreme situations, it might extend to the entire body.

To remedy this, says Wong, “You need to loosen your hands and arms, and learn to use other parts of your body to turn the bike. You should always strive to be light on the bars and use your legs and knees to aid in turning.”

As with all these symptoms, fixing the specific error (in

this instance, tight hands and arms) is important, but it’s just as important to examine the conditions that produced the symptom. Reduce your speed, relax and figure out what caused it in the first place. “Maybe your line was off, or you weren’t using good body position, or your entry speed was too fast, or there was some gravel in the turn that gave you a scare,” says Wong. “It’s your job to see that picture in its entirety-and act on it.”

3. Mid-Corner Braking

This occurs when a rider goes into a corner with too much speed, then tries to slow. “In my skills clinics, I always ask the group if they have committed this error,” he says.

“Almost everyone admits that they have. And frankly, I suspect those who don’t admit it are lying. It’s an extremely common mistake.”

Of course, there is nothing wrong with slowing in the corner if you can get away with it. “But if you are entering the turn or in the middle of it at speed and you say, ‘Gee, I wish I was going 5 mph slower,’ then it’s probably too late,” says Wong. The typical reaction is to hit the brakes. “And the rear brake is the worst offender, because you will almost certainly slide out if you use it aggressively in mid-corner.”

Wong explains that in any corner, you have a finite amount of traction. Let’s give it a number, say, 100. If you touch the brakes when you’re turning slowly on clean pavement, you may only use 20 percent of that. Really aggressive cornering at high speed will use up 80-90 percent of available traction. Then, when you tap the brakes, it can take you past the limit, with predictable results. Gravel, wet surfaces and pavement irregularities exacerbate this. >

The solution is simple: “If you detect this symptom in your own riding, slow down.”

4. Chopping the Throttle

This symptom, as with mid-corner braking, occurs when you are in a turn and you suddenly think, “I’m going too fast.”

As a reaction, you chop the throttle, which is exactly the opposite of what you should do. “It’s ironic that many of our normal inclinations are the opposite of what is actually good for us,” says Wong.

At lower speeds, this may do nothing worse than upset the chassis slightly. But if you’re playing Ricky Racer approaching the limits of traction when this occurs, the rear-to-front weight transfer caused by suddenly rolling off the throttle may take you past the limit, overloading the front of the bike. “And it’s typically the front end that will slide out when you chop the throttle,” says Wong.

“In my experience, most riders who exhibit this symptom feel they are going too fast-but they actually aren’t,” says Wong. “Rather than chopping the throttle, they should look through the corner and maintain their speed.” Chopping the throttle is also indicative of poor planning and corner entry, says Wong. “Your entry should be such that you can give the bike a little throttle all the way through. This balances the traction forces in the front and rear for optimum control.”

5. Mid-Corner Corrections

This is related to the previous two symptoms, because it involves a sudden response to your surroundings in mid-corner. For example, you attempt a sudden line change, either tightening your line or moving to the outside if your entry is too tight.

As with the previous two symptoms, a mid-corner correction can devour available traction. And if you are already at the limit, or the road conditions change, you may exceed the limit.

“The solution lies in the way you set up for the corner,” says Wong. “Ideally, you will have one initial input into the bar, and the corner will be a smooth arc.”

6. Anxiety

Most riders know the feeling of a great corner, where everything just clicks. But what happens when you have what Wong calls a “non-optimal emotional response?” In other words, you just don’t feel good. That might sound pretty vague as a basis for action, but actually, this “feeling” is extremely important. “Some of the best riders I know, when they have this feeling, are smart enough to click the pace down a notch until things feel right again,” says Wong.

If you are not feeling good, whether it’s from indigestion, a work-related concern or anything else, your riding performance is compromised. This symptom should be a wake-up call for you.

Many riders compound the situation by ignoring the symptom. They think, “If I only had more guts, I’d go faster,” says Wong. “They try to ride through it. And they crash. Whether you’re a new rider or an experienced racer, you can’t improve just by going faster and multiplying the effects of this symptom. It’s fine to challenge yourself on occasion but only when you’re ready and the conditions are right.”

Sometimes this anxious feeling results from riding with others who are faster. In the pressure to keep up, you can lose your cool and start making mistakes. “In these situations, it’s important to heed the signal and ride within yourself,” says Wong.

Putting it All Together

If there is one theme to Wong’s instruction, it’s self-awareness. “The mistake is not the symptom itself,” he says. “The mistake is pushing through the symptom in the hope that it will go away. A symptom should be your signal to click down, analyze the correction that’s required and ride within your skill level.” Doctor’s orders. □