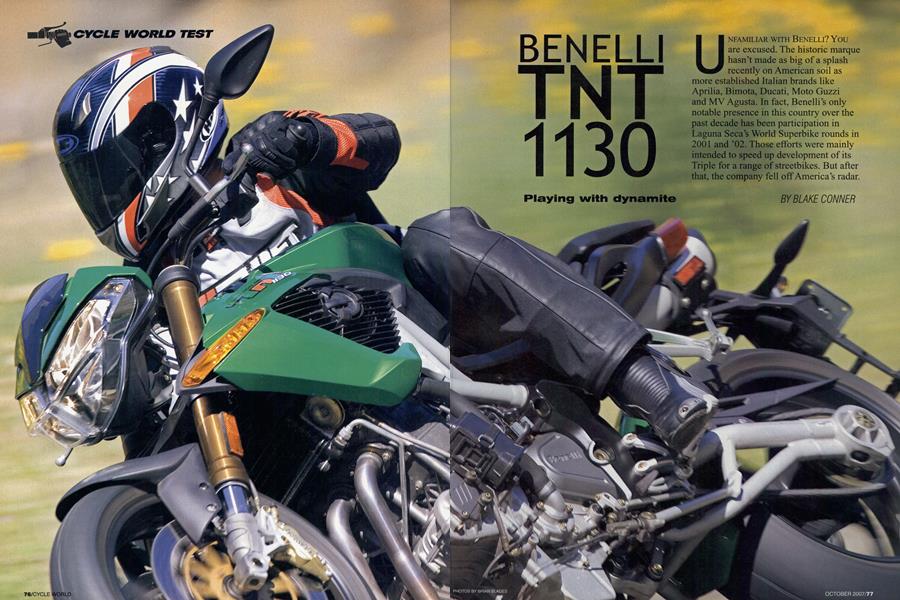

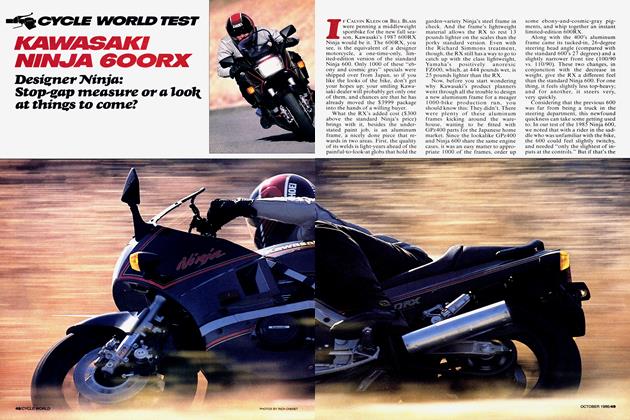

CYCLE WORLD TEST

BENELLI TNT 1130

Playing with dynamite

UNFAMILIAR WITH BENELLI? You are excused. The historic marque hasn't made as big of a splash recently on American soil as more established Italian brands like Aprilia, Bimota, Ducati, Moto Guzzi and MV Agusta. In fact, Benelli's only notable presence in this country over the past decade has been participation in Laguna Seca's World Superbike rounds in 2001 and '02. Those efforts were mainly intended to speed up development of its Triple for a range of streetbikes. But after that, the company fell off America's radar.

BLAKE CONNER

The Benelli Garage was created in 1911 by the family’s matriarch in order to provide employment for her six sons. Ten years later, the business morphed from repairing cars and motorcycles to building its first bike, a 98cc model, and later diversified into firearms, among other things. Competition was paramount to developing its products. One of the sons, Antonio “Tonio” Benelli, was quite a good racer and won four Italian championships aboard early singleand twin-cam 175cc racers. Tonio was later killed in a testing incident, but the small company’s racing involvement was just hitting its stride. Numerous victories on the Italian and European racing scenes included multiple wins at the Isle of Man TT, the most important motorcycle racing event of the era. Benelli managed to capture two 250cc Grand Prix world championships along the way (see “The Unexpected Champion,” page 80).

Things were looking up for the company on the racing front, but competition from the Japanese manufacturers on the showroom floor in the ’70s and ’80s was stiff—by ’89 the factory doors seemed closed for good. In 1996, Italian businessman Andrea Merloni attempted to resurrect the compa-

ny, spending a rumored 90 million euros in the process. The business plan depended on 50cc scooter sales to generate most of the income. Unfortunately, the collapse of the scooter market in Italy coincided with Benelli’s attempted revival, forcing the closure of the Pesaro factory in 2005.

Now back in the saddle again, Benelli has a fresh lease on life due to a large influx of capital from a new owner, Chinese company Qianjiang (see “Beyond the TnT,” page 83). That company is no stranger to two wheels and produces one million motorcycles and scooters a year for domestic and export markets. But don’t confuse Benelli’s ties to China; the bikes are currently 100 percent Italian-made, manufactured in Pesaro on the Adriatic coast.

What separates Benelli from other Italian bike-makers is the use of three-cylinder power, straying away from the V-Twins of Aprilia and Ducati and inline-Fours of MV Agusta. Originally, Benelli chose this configuration because it came with a displacement advantage in World Superbike competition. Unlike the original 900cc Tornado, though, the TnT (Tornado Naked Tre) has been punched out to 1130cc, packing more peak power and torque than Triumph’s excel-

lent 1050cc Triple.

Stuffed between the frame rails is a liquid-cooled, four-valve-per-cylinder, dohc engine of the company’s own design. Bore and stroke measure 88 x 62mm with an 11.5:1 compression ratio; a counterbalancer keeps buzz to a minimum. The TnT features a single fuel injector per cylinder and has an on-dash switch that allows the rider to choose between two EFI/ignition maps.

The Power Controller feature is no gimmick, but we’re not really sure why the rider would ever want the reduced-power option-which isn’t as well-mapped as the high-power mode.

On the Cycle World dyno, our test TnT produced 120 rear-wheel horsepower and 76 foot-pounds of torque in what we’ll call the “A” map. The “B” map only managed 104 hp/69 ft.-lb. The Power Controller switch is similar to the new Suzuki GSXR1000’s S-DMS selector, the differ-

ence being that the Suzuki’s setup softens power at lower rpm while still offering a smooth power delivery throughout the rev range. Unfortunately, the Benelli’s B map undulates like a rollercoaster below 6000 rpm and has a huge plunge at 5200 rpm. If the argument is that the B map is better suited to tricky surface conditions, we disagree; the poorly mapped fuel delivery would make traction more difficult to find than the smoother high-powered map. Bottom line: Just leave the bike in A mode.

One of the nicest attributes of Triple power is the lowto midrange torque. The TnT is no exception, producing 60 ft.-lb. of torque as low as 2500 rpm and making launches effortless. In A mode, the torque curve has a few mild dips but stays meaty throughout the rev band. Peak power is impressive with a nice linear rise up to the bike’s 9500-rpm rev-limiter.

On most roads, the broad spread of torque allows you to shift into one gear and just leave it there. Exiting tight corners, the rear Dunlop claws for traction but the power delivery makes things predictable and drama-free. Another reason to leave it in one cog and not row the gearbox is that the engine has a prodigious amount of compression braking, which can unsettle the rear of the bike entering corners, since no slipper clutch is fitted.

The six-speed gearbox has short, positive throws but can feel notchy if shifts aren’t synched perfectly; nail them right and action is buttery-smooth. Finding neutral at stoplights can be a little difficult at times. Besides being notchy and having the elusive neutral, the transmission occasionally doesn’t immediately return to the center position, not allowing another upshift. Not the nicest gearbox we’ve tried.

There are a few other details a TnT owner will have to adjust to, as well. The Benelli likes to spend a little more time warming up than most bikes; it would occasionally sputter and die when cold, fueling poorly for the first mile or so before clearing out its lungs and running cleanly. Of course, this just gives the rider an opportunity to stand back and admire the bike while getting geared up, something that used to be the norm and has fallen by the wayside in this age of electronics and FI. Our TnT never got what we would consider great fuel mileage, hovering around 30-32 mpg in

normal riding conditions. The twin side-mounted radiators and shrouds are definitely the bike’s styling signature, but the pair of fans always seems to be running, making us wonder how efficient the cooling really is.

Anchoring the Naked Tre’s chassis is a frame that uses round steel tubing for the trellis spars and steering head, and is glued and screwed into cast-aluminum middle sections. The swingarm mimics the look of the frame and is also formed using steel tubing, then fitted with eccentric chain adjusters. The 50mm Marzocchi inverted fork is non-adjustable and the single Extreme Technology shock only has provisions for preload and rebound-damping adjustment.

In most riding situations, the suspension was more than adequate, providing good damping on all but the roughest roads. It was there and on faster sections that the lack of adjustability became an issue. Better damping circuits would allow the suspension to deal more effectively with a quick succession of bumps.

Standard-mount four-piston Brembo calipers with 320mm discs are very good brakes, but they don’t quite have the level of bite and feel that the same company’s radial-mount stoppers provide. Out back is a twin-piston caliper and 240mm disc; our TnT’s rear brake squealed from Day One. For those looking for better components, Benelli also offers the Naked Tre Sport, which gets fully adjustable suspension front and rear, and Brembo radial-mount brakes for $1200 more than the $15,499 TnT.

On backroads, the Benelli is a blast. The high-bar, uprightseating-position naked formula is hard to beat for 90 percent of sport riding. Cranking up the tight side of Southern California’s Palomar Mountain was a perfect place for the TnT to strut its stuff. The moto-style bars provide plenty of leverage to flick the bike into corners, and once on the side of the tire, the Naked Tre is trustworthy, stable and planted. With the torquey engine, it’s a great combination.

On the highway, the suspension offers a smooth ride.

The seating position is very neutral, with an easy reach to the bars; footpegs are high enough to stay off the tarmac but low enough for longer rides. Extended stints in the saddle are limited by a narrow and thinly padded seat that doesn’t allow the rider to move around much to keep comfy.

Comments about passenger accommodations were better than expected for this type of bike; not a complaint was logged. Wind protection is fairly good

for a naked until the speeds get up over 80 mph, then buffeting forces you to either tuck in or think about building up your neck muscles at the gym.

Unlike a multitude of exotic Italian bikes, many of the TnT’s basic features are riderfriendly. The mirrors offer a clear rearward view of more than elbows, and the handlebar switches are straightforward and easy to use. The dash (with a cool blue backlight) provides a lot of information once you learn the secret combination of button clicks needed to scroll through the screens. There’s even a lap timer, operated by the starter/mode button once the bike

is running, in case you take your TnT to the track or want to know exactly how long it takes to get to work.

A little raw and a bit brash, the TnT is more hooligan than many of the thoroughbreds offered by the Italian competition. The love-itor-leave-it styling is sure to evoke a response but will never be called dull and always draws a crowd. Benelli logs another entry into what is becoming a long list of fun nakeds. If you can’t have a blast on this bike, you’re simply missing the point. □