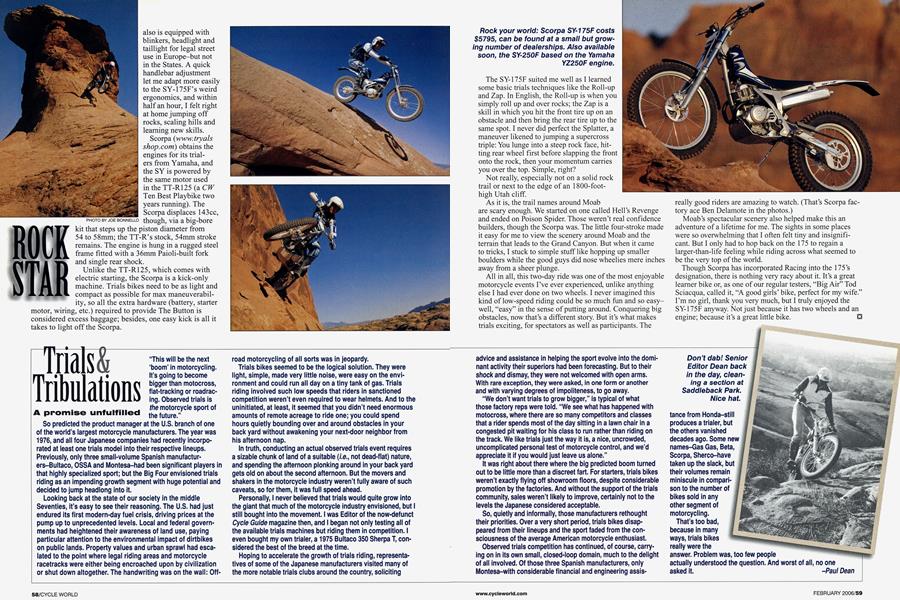

Trials & Tribulations

A promise unfulfilled

“This will be the next ‘boom’ in motorcycling. It’s going to become bigger than motocross, flat-tracking or roadracing. Observed trials is the motorcycle sport of the future.”

So predicted the product manager at the U.S. branch of one of the world’s largest motorcycle manufacturers. The year was 1976, and all four Japanese companies had recently incorporated at least one trials model into their respective lineups. Previously, only three small-volume Spanish manufacturers-Bultaco, OSSA and Montesa-had been significant players in that highly specialized sport; but the Big Four envisioned trials riding as an impending growth segment with huge potential and decided to jump headlong into it.

Looking back at the state of our society in the middle Seventies, it’s easy to see their reasoning. The U.S. had just endured its first modern-day fuel crisis, driving prices at the pump up to unprecedented levels. Local and federal governments had heightened their awareness of land use, paying particular attention to the environmental impact of dirtbikes on public lands. Property values and urban sprawl had escalated to the point where legal riding areas and motorcycle racetracks were either being encroached upon by civilization or shut down altogether. The handwriting was on the wail: Offroad motorcycling of all sorts was in jeopardy.

Trials bikes seemed to be the logical solution. They were light, simple, made very little noise, were easy on the environment and could run all day on a tiny tank of gas. Trials riding involved such low speeds that riders in sanctioned competition weren’t even required to wear helmets. And to the uninitiated, at least, it seemed that you didn’t need enormous amounts of remote acreage to ride one; you could spend hours quietly bounding over and around obstacles in your back yard without awakening your next-door neighbor from his afternoon nap.

In truth, conducting an actual observed trials event requires a sizable chunk of land of a suitable (/.e., not dead-flat) nature, and spending the afternoon plonking around in your back yard gets old on about the second afternoon. But the movers and shakers in the motorcycle industry weren’t fully aware of such caveats, so for them, it was full speed ahead.

Personally, I never believed that trials would quite grow into the giant that much of the motorcycle industry envisioned, but I still bought into the movement. I was Editor of the now-defunct Cycle Guide magazine then, and I began not only testing all of the available trials machines but riding them in competition. I even bought my own trialer, a 1975 Bultaco 350 Sherpa T, considered the best of the breed at the time.

Hoping to accelerate the growth of trials riding, representatives of some of the Japanese manufacturers visited many of the more notable trials clubs around the country, soliciting advice and assistance in helping the sport evolve into the dominant activity their superiors had been forecasting. But to their shock and dismay, they were not welcomed with open arms. With rare exception, they were asked, in one form or another and with varying degrees of impoliteness, to go away.

“We don’t want trials to grow bigger,” is typical of what those factory reps were told. “We see what has happened with motocross, where there are so many competitors and classes that a rider spends most of the day sitting in a lawn chair in a congested pit waiting for his class to run rather than riding on the track. We like trials just the way it is, a nice, uncrowded, uncomplicated personal test of motorcycle control, and we’d appreciate it if you would just leave us alone.”

It was right about there where the big predicted boom turned out to be little more than a discreet fart. For starters, trials bikes weren’t exactly flying off showroom floors, despite considerable promotion by the factories. And without the support of the trials community, sales weren’t likely to improve, certainly not to the levels the Japanese considered acceptable.

So, quietly and informally, those manufacturers rethought their priorities. Over a very short period, trials bikes disappeared from their lineups and the sport faded from the consciousness of the average American motorcycle enthusiast.

Observed trials competition has continued, of course, carrying on in its own small, closed-loop domain, much to the delight of all involved. Of those three Spanish manufacturers, only Montesa-with considerable financial and engineering assis-

tance from Honda-still produces a trialer, but the others vanished decades ago. Some new names-Gas Gas, Beta, Scorpa, Sherco-have taken up the slack, but their volumes remain miniscule in comparison to the number of bikes sold in any other segment of motorcycling. That’s too bad, because in many ways, trials bikes really were the

answer. Problem was, too few people actually understood the question. And worst of all, no one asked it. -Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontWorld's Fastest Indian

February 2006 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsBeemer Report Card, Summer Semester

February 2006 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCUntying Knots

February 2006 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

February 2006 -

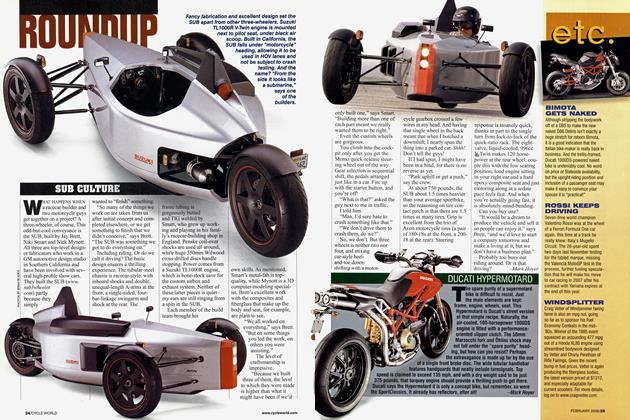

Roundup

RoundupSub Culture

February 2006 By Mark Hoyer -

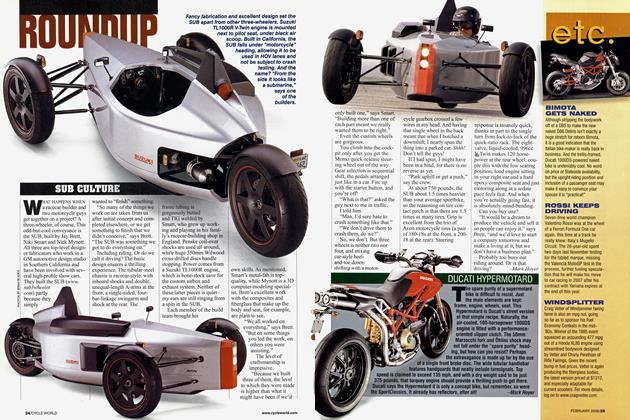

Roundup

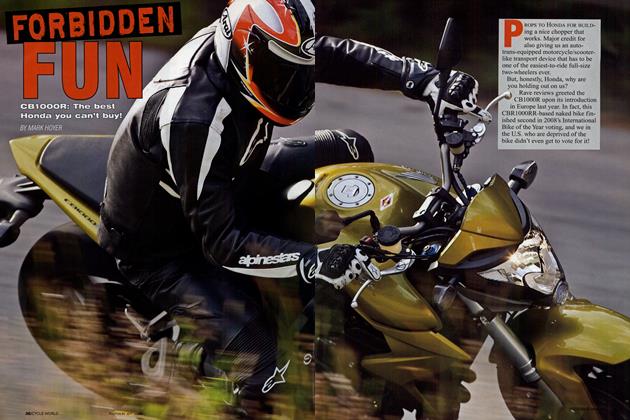

RoundupDucati Hypermotard

February 2006 By Mark Hoyer