Beasts of burden

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

DECISION TIME. I STEPPED OUT OF DOORS with the usual morning cup of coffee grafted to my hand and looked at the sky, trying to gauge the weather. The sky was a glorious blue in all directions, but it was chilly and windy.

So, ride or take the car? That was the question.

Sixty miles away, far over the western horizon, was the town of Dodgeville, Wisconsin, where my friend Denny Marklein ran a body shop.

And in that body shop was a massive yet somehow magnificent 1953 Cadillac Fleetwood, a car from Texas that I’d bought on eBay in a moment of temporary delirium. It only needed everything, and Denny was repainting it for me.

“How’s it look?” I asked him over the telephone.

“Well, we’ve removed all the paint, and it looks like a prehistoric DeLorean. The lower cross-bar on the front bumper is pretty rusty, so you’ll probably want to get it rechromed before we put the grille back together.”

“I’ll be over tomorrow morning to pick it up,” I said.

And now it was tomorrow morning.

Normally, when I have to carry around big ugly industrial-strength items, I just take the car. Put down some cardboard and throw the pieces in the trunk. But this wasn’t normally.

Premium unleaded, which my little unnaturally aspirated overachiever of an econobox is supposed to use (though I often cheat with mid-grade) had just hit $3.29 per gallon at the nearest gas station.

The CEO of this very oil company had just retired, according to the morning paper, with a golden parachute payment larger than the GNP of Luxemburg, proving Hunter S. Thompson’s thesis that we really are a generation of swine.

I was taught in school that one difference between humans and livestock is that humans have a sense of shame. So much for that theory.

Corporate greed aside, however, the high cost of fuel appeared to be only a symptom of several other looming problems, including declining global petroleum reserves, an ever-thirstier world economy and our own national drinking problemincluding mine. Not a happy combination.

Anyway, I was in a suddenly minimalist mood that morning, and the thought of using even my 30-mpg car to drive 120 miles to pick up a big dirty chunk of Cadillac bumper gave me pause. Fourteen dollars worth of fuel, 20 pounds of carbon dioxide spewed into the air. All to put another ancient (but very swanky, you must admit) gas-guzzler back on the street.

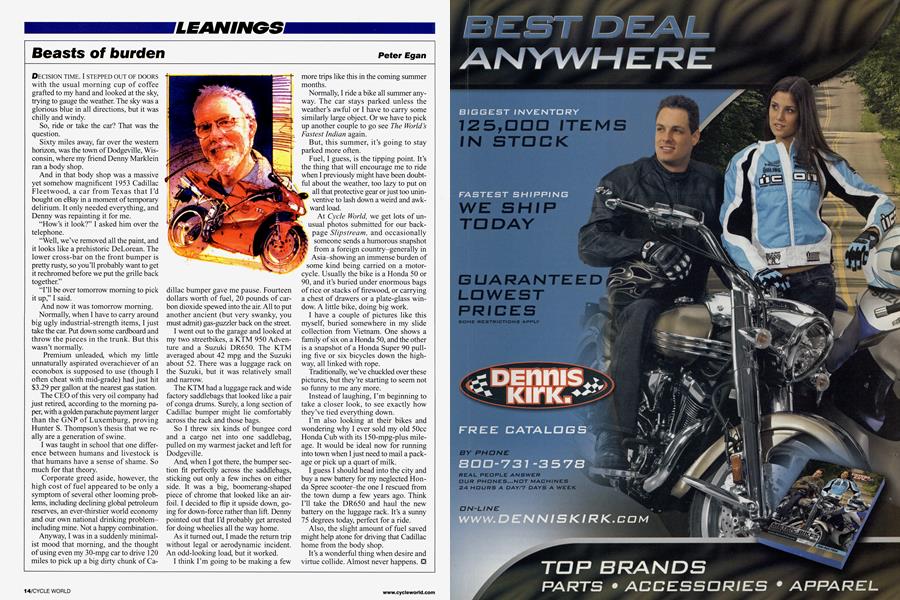

I went out to the garage and looked at my two streetbikes, a KTM 950 Adventure and a Suzuki DR650. The KTM averaged about 42 mpg and the Suzuki about 52. There was a luggage rack on the Suzuki, but it was relatively small and narrow.

The KTM had a luggage rack and wide factory saddlebags that looked like a pair of conga drums. Surely, a long section of Cadillac bumper might lie comfortably across the rack and those bags.

So I threw six kinds of bungee cord and a cargo net into one saddlebag, pulled on my warmest jacket and left for Dodgeville.

And, when I got there, the bumper section fit perfectly across the saddlebags, sticking out only a few inches on either side. It was a big, boomerang-shaped piece of chrome that looked like an airfoil. I decided to flip it upside down, going for down-force rather than lift. Denny pointed out that I’d probably get arrested for doing wheelies all the way home.

As it turned out, I made the return trip without legal or aerodynamic incident. An odd-looking load, but it worked.

I think I’m going to be making a few more trips like this in the coming summer months.

Normally, I ride a bike all summer anyway. The car stays parked unless the weather’s awful or I have to carry some similarly large object. Or we have to pick up another couple to go see The World’s Fastest Indian again.

But, this summer, it’s going to stay parked more often.

Fuel, I guess, is the tipping point. It’s the thing that will encourage me to ride when I previously might have been doubtful about the weather, too lazy to put on all that protective gear or just too uninventive to lash down a weird and awkward load.

At Cycle World, we get lots of unusual photos submitted for our backpage Slipstream, and occasionally someone sends a humorous snapshot from a foreign country-generally in Asia-showing an immense burden of some kind being carried on a motorcycle. Usually the bike is a Honda 50 or 90, and it’s buried under enormous bags of rice or stacks of firewood, or carrying a chest of drawers or a plate-glass window. A little bike, doing big work.

I have a couple of pictures like this myself, buried somewhere in my slide collection from Vietnam. One shows a family of six on a Honda 50, and the other is a snapshot of a Honda Super 90 pulling five or six bicycles down the highway, all linked with rope.

Traditionally, we’ve chuckled over these pictures, but they’re starting to seem not so funny to me any more.

Instead of laughing, I’m beginning to take a closer look, to see exactly how they’ve tied everything down.

I’m also looking at their bikes and wondering why I ever sold my old 50cc Honda Cub with its 150-mpg-plus mileage. It would be ideal now for running into town when I just need to mail a package or pick up a quart of milk.

I guess I should head into the city and buy a new battery for my neglected Honda Spree scooter-the one I rescued from the town dump a few years ago. Think I’ll take the DR650 and haul the new battery on the luggage rack. It’s a sunny 75 degrees today, perfect for a ride.

Also, the slight amount of fuel saved might help atone for driving that Cadillac home from the body shop.

It’s a wonderful thing when desire and virtue collide. Almost never happens.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue