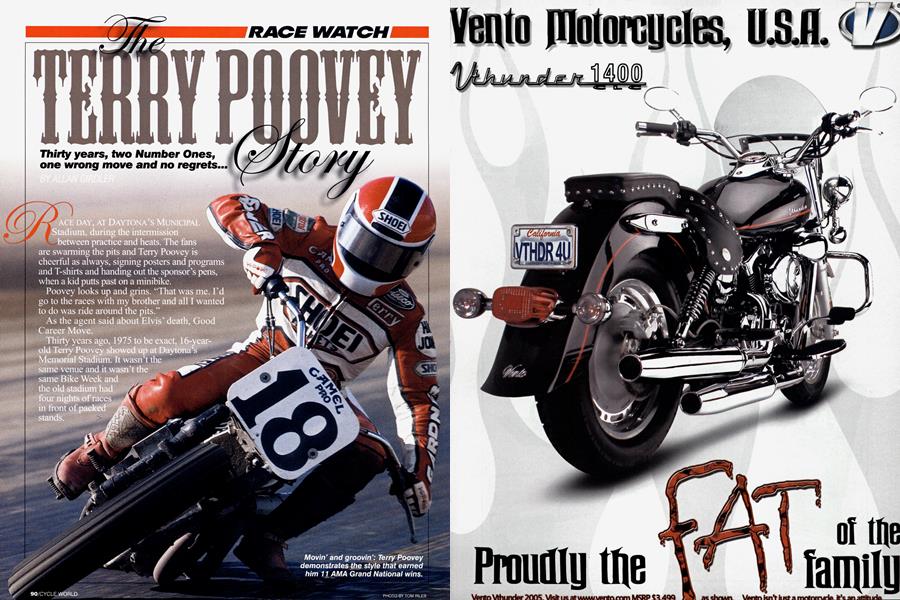

The TERRY POOVEY Story

RACE WATCH

Thirty years, two Number Ones, one wrong move and no regrets...

ALLAN GIRDLER

RACE DAY, AT DAYTONA'S MUNICIPAL Stadium during the intennission between practice and heats The fans are swarming the pits and Terry Poovey is cheerful as always, signing posters and programs and T-shirts and handing out the sponsor's pens, when a kid putts past on a minibike.

Poovey looks up and grins. "That was me. I'd go to the races with my brother and all I wanted to do as ride around the pits

As the agent said about Elvis' death, Good Career Move

4:

Poovey had replaced his minibike with a Bultaco, he’d earned his Junior points and he won two of the four mains that week. He made Expert, and the next year, still riding the Bultaco, he won the Talladega Short-Track National.

Eleven national wins and 30 years later, Poovey is hanging up his steel shoe. He’s not leaving racing, though, and he doesn’t spend much time looking back.

This is, for the most part, a success story. Poovey clearly had talent; no rider has ever lucked into a Grand National main event. He knew how to ride, and he also knew how to go racing, which isn’t quite the same thing.

For one instance, after Yamaha revived the classic Vincent’s cantilever rear suspension, the single-shock principle looked promising. Inventor Joe Bolger, now in the AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame, came up with a design. Tuner/retired rider Doug Sehl built a Harley-Davidson XR-750 with Bolger’s suspension. Some leading lights tried it and withdrew, so Sehl signed on Poovey, who’d been over-riding his own bikes, and they won the Meadowlands, Pennsylvania, Half-Mile, first win for a monoshock XR, followed by two wins on the fabled Indianapolis Mile.

In the early 1980s, there was sort of an imbalance, in that H-D made the only competitive milers, while Triumphs and Yamahas were better in TT and the twostrokes ruled short-track. Then Honda (and, to much less effect, Yamaha) got interested in the AMA’s series, the only major league Honda hadn’t ruled.

Big Red began in the spirit of the AMA’s rules, which required racing engines to be based on production machines. Honda took the mild-mannered CX500 road bike and made some astonishing changes to make it into a dirt-track contender.

Also in Honda tradition, in order for the public to know it was the machine and not the man winning those titles, Honda hired riders who weren’t yet champions, namely a kid from Louisiana, one Freddie Spencer.. .and Terry Poovey.

This looked like a good move for all parties, at least on paper. Modified production bikes were replacing the pure racing 750s as the premier roadrace class. Honda had a strong contender there, and could easily certify a 250cc two-stroke for AMA short-track and a twoor fourstroke Single for TT. Plus, for the miles and half-miles, the CX-based bike gave Honda a full house.

But the new machine was a disaster. It wouldn’t go fast and it wouldn’t turn. Spencer was as ferocious on-track as he was shy in the press room. To watch him arm-wrestling the bars, standing on the front wheel, draping himself over the side, all to no avail, was to not believe how much effort could result in so little performance.

Poovey wasn’t as visible. For him, the NS750 just didn’t work.

Pause here for cultural contrast. In the West, a certain amount of griping on the job is tolerated, perhaps even expected. In the East, when you don the team jersey, you sing the team song and recite the team slogan, period.

Fans who know Spencer only as today’s color commentator on television will wonder at this, but the Spencer of 1981 was an impossible interview because he was too shy to say more than, “Hi.”

Poovey hails from Texas, where talk isn’t cheap; it’s a hobby and an art. He was frustrated. He’d gone from top-five to not making the main event. He knew ’t his fault and he said as much, friends but to the press and, of course, the press reported what they’d heard-our job, after all.

That wasn’t what Honda was paying for. First step, they signed tuners who’d done well on American tracks. Next they bought a Harley XR-750, shipped it to the engineering center, took it apart and asked themselves, in effect, what would Harley have done if they had our resources?

Then, they did it. They did what the other factories, including Harley-Davidson did, they slipped through the gaps in the letter of the law, forget the spirit, and introduced the RS750, a nominal Honda Shadow except it matched the XR’s narrow angle and nearly copied bore and stroke and came with overhead cams, not pushrods. Okay, it was a newer and better XR-750, from Day One. Poovey got to test the new machine, but it wasn’t right, yet.

Late in November, 1983, Gene Romero, the retired AMA #1 who’d lived through the humiliation of the CX debacle and kept his jaw firm and shut, announced Honda’s new squad.

Spencer was promoted, to go to Europe and take the world roadracing laurels from Yamaha and Kenny Roberts, which he, of course, did.

The American dirt team would be former #1 Ricky Graham and an up-andcoming Texan named Bubba Shobert.

Second pause, for culture and politics. Graham won the AMA title as a privateer, tuned by Tex Peel, a cranky outsider who also allowed himself freedom of expression. They’d beaten the Harley team, on Harleys, so there was no way H-D would ever put Graham on the payroll.

It’s fair to suspect that Poovey’s success on ex-team member Sehl’s XR-750, the one that moved suspension up another notch, could have hurt him with Milwaukee.

That’s a hunch. Poovey’s dismissal from Honda was plainly a response to his complaints, which were taken as disloyalty.

As racing fans of a certain age are aware, Graham and Shobert both won the AMA title, riding the new and improved Honda 750s as well as the TT and track Singles. Shobert went on to follow Spencer and win in roadracing as well.

And Terry Poovey? By this time he’d married Kathey, a lovely, charming and supportive wife, and in due course they had Katey, as cute a baby as ever the infield.

Here’s where knowing how to go racing comes in. The privateer, then even stronger than now, needs outside help. The prize money alone won’t pay the racing bills, never mind the rent and shoes for the kids.

Poovey has always been cheerful and outgoing, straight as the proverbial arrow. It turns out he was a natural entrepreneur, the guy who can go out and enlist sponsors. Better still, they got their money’s worth.

This isn’t always the case. There are endless horror stories about racers who skimmed and cheated and didn’t come through when it counted.

Poovey’s sponsors never had to worry. To be in the infield during the fan’s visiting period, as mentioned earlier, was to see a line of folks, there to visit and buy and gossip. Sure, in a business sense it would be difficult for, oh, California trucking magnate Ted Sakaida or Roy Plattell, the attorney behind IstLegal, to prove that backing Poovey’s dirt-track team pulled in enough business to offset the cost.

Didn’t matter. They enjoyed going to the races and being part of what really is, deep down, a family sport. Their backing meanwhile meant that while Poovey usually had a day job, when the racing season began he could put together a program to get him through the series without taking food from the family’s table.

Speaking ironically, going private means you can pick and choose your brands, so here Poovey was, having said on the record and while he was on the Honda team, that if he nicked his finger it probably would bleed orange and black, that is, Harley colors. When Honda’s RS750, the H-D copy not the CX500 offshoot, was the best machine, Poovey rode one. And when Honda had proved the point, had defeated Harley and Yamaha even when Roberts rode a Harley, Big Red quit winners, dropped out of the AMA dirt series, Terry and brother Ted became the guys who kept the Hondas running and fielded the fastest examples.

By that time, of course, the AMA rules had been juggled to keep the older Harleys competitive, so Poovey never won an AMA national on the RS. His only AMA win for Honda was in fact the 1983 short-track at Houston, when he was on 1) the Honda payroll and 2) a motocrossbased two-stroke Single.

Again during this time frame, the AMA split the roadraces off from the Olympian mode, the notion of using road circuits, miles, half-miles, TTs and short-tracks for the national championship. This was good for Honda and Yamaha (and would have been good for the other two of the Big Four if they’d cared, which they didn’t).

The big guys had models for each type of racing and Honda simply won the Superbike series for the factory and left the other venues alone.

What this meant for Terry Poovey was too wide a jump: Roadracing required different machines and schedules, never mind techniques and sponsors, so roadracing was a place he never went.

Dirt-track theory says each venue has a different emphasis. The mile requires enough power to keep up with the lead pack, the grit to keep the power on, and the planning and cunning to be in the right place for the last two turns. TT calls for exuberance and control when you’re out of control, witness Eddie Mulder in the old days, Chris Carr and Joe Kopp or the Hayden brothers now. The half-mile takes a different type of control. The 750s have too much power, so the throttle hand and the chassis setting focus on only handing out what the track and the tires will take.

Short-track features what the basketball writers call A Sense of Where You Are. The bikes are light and overpowered, 200 pounds and 60-plus horsepower, and they’re spinning and sliding most of the time. The best short-trackers go high here, low there, pass on the outside or tuck inside, always with the sense of where they are each lap and what the other guys are doing.

Going by the record, Poovey had two mile wins in AMA nationals, both on Harley XRs. He never won a roadrace and wasn’t too comfortable in TT, but he won four short-tracks and five half-miles.

This indicates half-miles were his best side, but when color commentators talked about Terry Poovey, it was always about short-track.

Why? Mostly it must have to do with Daytona. As hinted earlier, back before buying rude T-shirts was what bikers liked best, Bike Week was about racing. So the stands were packed night after night, and one day Poovey checked the records and found that over his career, he had won 20yes 20-main events at Daytona.

Plus, during his 20 years as a privateer dirt-tracker, shorttrack was where he did best. He won the AMA national at Daytona in 1997, and he did it again in 2000, so if you’re a racing fan and if you have been to Bike Week while Poovey was racing, odds are you’ve seen him win a short-track.

For another boost to Poovey’s career if not the sport itself, media colossus Clear Channel decided several years ago to compete with the AMA and sanction a dirt-track championship.

They did a clumsy job. The rules were confusing and the politics intense, and after the crowds and the ratings plummeted, they called the thing off.

But what it meant for the dirt-track community, while it lasted, was more paychecks.

For Poovey, it was paychecks and championships. He won the highly visible Del Mar ShortTrack and the Fonnula USA title, on an ATK, in 2001. He repeated the next year, except that Honda had brought out the CRF450R, and he’d gained backing from a Dallas Honda dealer, so he was back with Big Red. And so, as the accountants say, here’s the bottom line: Terry Poovey had raced, and won, and enjoyed himself for 30 years. At the finish of 2004, he had done as much racing-in the saddle that is-as he needed to do. His wife has a good career with American Airlines, their daughter is doing well in college, time for a change.

So Poovey joined lifelong pal Kenny Tolbert and semi-permanent AMA Grand National Champion Chris Carr in their Ford-backed team. He’ll do, Poovey says, whatever needs to be done to keep those #1 plates coming, but from the sidelines not the saddle.

How’s he feel about all this, for instance his history with Honda?

Yes, another pause here. As with most people who are doing what they wanted to do, and are doing it well, Poovey wouldn’t change the steps in the path that led to where he is now.

Poovey checks the record: He made 348 race starts, was in the top-10 210 times and the top-five 80 times, this with the 11 AMA national wins and the two FUSA titles.

“Oh yeah,” he says, “I would have liked to win more races, and won the titles Graham and Shobert won. “But I’d rather be me.” □

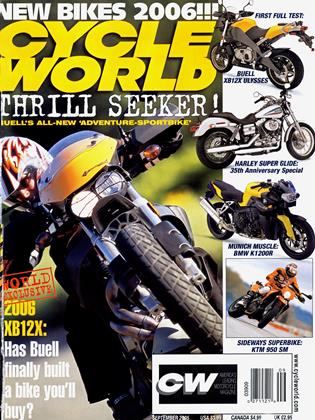

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontHauiin'

September 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsIn Praise of Cop Bikes

September 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCMarket Value

September 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2005 -

Roundup

RoundupFuture Road-Burner Revealed?

September 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupVictory's Jackpot

September 2005 By Calvin Kim