ASCOT PARKED

Birth and Death of a Cheap Bike

JOHN N. OLSEN

FUNNY HOW LIFE THROWS YOU A CURVE BALL. AFTER five tough years and a graduate degree, I had resigned myself to a tie-wearing career at Boeing or GM when I stumbled across an “Engineer Wanted” ad for Honda R&D in Los Angeles. I had my résumé in the mail within minutes. Shockingly, Honda responded and flew me out to California for an interview. I proved to them that I didn’t drool or go into involuntary pirate imitations, and that I could eat sushi, so they offered me a job! That May,

I pulled up to the small Honda R&D building in Torrance, their newest and proudest employee.

At that time, R&D in this country (known inside Honda as HRA, for Honda Research America) was small, maybe 30 employees covering everything but power products.

Most of the employees were Japanese citizens working in this country to absorb American culture so that the products they would later create would satisfy our desires.

The majority of hands were employed sculpting clay in a locked-down styling studio. The “engineering” department numbered only six, and we did almost anything but engineering. Most of our time was spent guiding Japanese engineers around L.A. and the United States, or gathering up competitors’ motorcycles and aftermarket parts to ship back to Japan for evaluation. A small but very enjoyable fraction of my working hours was spent “testing” motorcycles and cars. Testing meant charging around backroads, or blasting around Saddleback Park or Indian Dunes (remember them?) on dirtbikes. On weekends, I could check out our Ducati 900SS, a bevel-gear ’78, and explore the canyons of Greater Los Angeles. Sun, surf, bikinis, mountains, road bikes, motocross bikes...I had died and gone to heaven. Granted, heaven had more smog and heavy traffic than predicted by most theologies, but did I mention the bikinis and Ducatis?

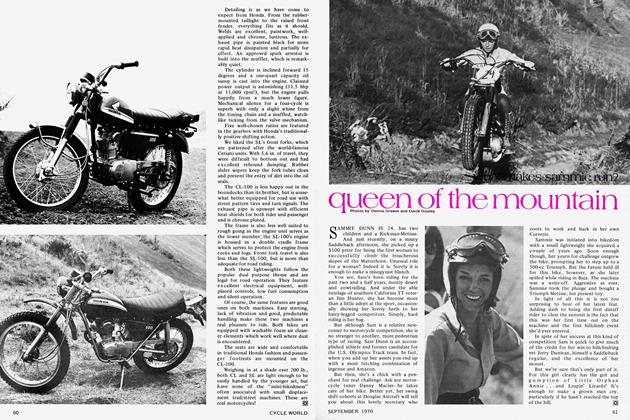

Not too long after I showed up, so did the XR500 prototypes. The XR had a great-looking engine, and it gave me an idea. I’d always been fascinated by British Singles, especially BSA Gold Stars, and it didn’t take me long to begin to scheme about a classic street Single, but one with Japanese electrics and no oil leaks. My suggestion met with support from my American co-workers and my Japanese boss, and soon I was sketching and filling out pr1oposal forms. Japan sent an engine and carburetor and wiring harness, and the engine and I were soon bound for Oceanside, where Jeff Cole of C&J Frames helped me lay out a minor variation of one of his dirt-track frames with geometry appropriate for a road bike. By this time, HRA had moved to a bigger building near the Torrance Airport (a good thing, as not long after, the nearby Mobil refinery blew sky-high!), and there was an excellent upholsterer right down the street who built a saddle based on a buck that I carved from foam. I welded up a Triumph-like 2-into-l exhaust system from sections of pipe, and we adapted a CB400F gas tank. Twin Fox Air Shox, a CB400 fork, Comstar wheels, CB400F low bars-it wasn’t too long before we had a complete, and very pretty, motorcycle.

Before the bike could be tested or tuned (“John50«, we are not tunas!” as my boss liked to say), long before I was ready to see it go, the one and only prototype was in a shipping crate, heading for Japan. Soon after, I too was on my way. My boss, another Japanese HRA employee (a stylist assigned to be my “minder”) and I were headed to Asaka, home of Honda R&D, to present my bike to decision-makers to convince them that if they built it, Americans would buy it. Maybe. Well, I would anyway.

Soon, this shy Midwesterner was facing the Honda Board of Directors, an august group including the legendary Mr. Irimajiri, one of the superb engineers behind Honda’s six-cylinder racing engines and the soon-to-be CBX. Mr. Sato, my boss, was there to “interpret” my comments. The directors would ask a question in Japanese, Mr. Sato would translate, I would answer in English, and he would translate to Japanese. His translation was almost always much longer than my original. The meeting seemed to go well-I talked of my belief that U.S. riders would be attracted to a serious motorcyclist’s street Single with an emphasis on light weight, good suspension, great brakes and great looks-a Japanese Gold Star, in other words. In my boss’ translations, I picked up the word “flat-tracker” quite often, reflecting the fact that we had discussed the idea that a street-tracker concept might be a good alternative. The meeting adjourned, and every member of the board came up to me and greeted me. In fluent English!

The next day, we returned to R&D and were invited to look at what the engineers had done to “my” bike. Overnight, it had grown an electric starter. “But, Mr. Sato, I’d told them how important it was to keep this bike simple and light for real enthusiasts who don’t mind kick-starting,” I protested. “John-5««, with no electric starter, there can be no product. We must have electric starter,” came the reply.

The next week passed in a whirlwind of fabulous Japanese corporate hospitality. I was wined and dined and guided and pampered. We went to Osaka where Japanese schoolgirls tittered and pulled my blonde beard. We went to the Suzuka GP track, where I scared my trials-riding self silly on a CB900F, and experienced “we-are-not-tunas” speed wobbles on my Single. We walked through HRC. We strolled Mugen’s warehouse, noting strange cylinder blocks with bores for five tiny pistons. We visited Mr. Irimajiri’s house. We sat in traffic near Mt. Fuji and ate raw salmon for breakfast. I was treated with stunning consideration and care. Japanese culture? Okay by me!

Back in the States, time passed, and I got bored and frustrated with the then-total lack of engineering design being done at HRA. It was clear that if I wanted to pursue my design dream, I needed to learn Japanese and move to Asaka. Not possible, in other words. I left the company 11 months after I joined and went to Boeing, where I learned a lot and was just as bored, but in Seattle rather than L.A.

Finally, several years later, the Honda FT500 was announced.. .and I was rather disappointed. The bike’s real creators had opted for the street-tracker option,

hence the FT (flat-track) moniker, but the bike had the electric start, a detuned engine (to meet Honda’s rigorous road-bike reliability requirements), cast wheels, and a good bit of additional weight. It was pretty and comfortable, and very practical in town, but it needed about 15 more horsepower, 40 fewer pounds, and suspension with actual damping (not a strength of production Hondas in those simpler days). And I hadn’t designed a single part on the bike; I’d merely sparked its creation. It was like meeting an unknown bastard son by surpriseI’d been there for the conception, but hadn’t changed any diapers or guided its growth and personality. It was a stranger. I had not been the “tuna.” I owned one for six months, then sold it and moved on.

Despite good reviews, the bike didn’t sell well-35 horsepower, more or less, just didn’t excite the general public. The bike was imported for two years, ’82 and ’83, then dropped in this market. Languishing in warehouses and dealerships, by 1984 you could buy a new Ascot for less than $1000. They eventually dropped to the hundreds of dollars on the used market, but now are climbing again in value. A very good FT500 can still be had for $ 1000 or less-a fine transpo bargain, but not quite a Gold Star. Beware that if you intend to really use an FT500 as a cheap main ride, parts are getting difficult to find, and no longer carried by Honda.

The FT500 still has a small-but-loyal following. There is a Yahoo! user group dedicated to the bike, and those who love them still seek them out and ride them. They have been largely reliable, with the exception of the electric starter (I knew it would end in tears!), rotting exhausts and cam-tensioner problems shared with the XL and XR versions. The ’89 GB500 came much closer, still selling poorly, but the concept of a Japanese Single in the British vein is supported by the fact that good GBs go for up to $5000.

Now, a street-tracker with an Africa Twin engine, good suspension, killer styling. I’m sure it would sell...

John Olsen enjoys exploring the wilds of the Portland, Oregon, area on his Suzuki DR650. A Cornell grad, he worked at Honda, Boeing, Kenworth and HP as a mechanical engineer. A pioneering mountain biker with 25 years writing for bicycle magazines, this is his first CW submission.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue