Just for kicks

SER VICE

Paul Dean

In one of last year’s issues, I read about a Harley-Davidson Twin Cam project bike that Cycle World built in honor of H-D’s 100th anniversary. As I recall, that bike was equipped with a functional aftermarket kickstart mechanism. I’m building a retro-look 2000 Softail and would like to install a real kicker on it, but I lost that issue and can’t find another one. Could you fill me in on the particulars for that conversion?

Eddie Lynch Lubbock, Texas

The kickstart pieces for our “Project 100” Harley (October, 2003, and January, 2004, issues) came from Custom Chrome, Inc., which now sells two different conversion kits. The one we used sells for $555 and requires complete transmission disassembly for replacement of the stock mainshaft with one that connects to the kicker. Since then, CCI has added another conversion that lists for $320 and does not require mainshaft replacement, so transmission disassembly is not required. We know that the $555 unit works quite well, since that bike still is being ridden by Editor David Edwards and still is kickstart-only, but we have no experience whatsoever with the $320 kit.

This conversion also works best if you replace the stock ignition system with one

that is programmable. The stock system will not produce a spark until the ignition module receives at least two firing pulses from the pickup trigger; it needs those pulses to index itself and know which cylinder is firing and when. With electric starting, you never notice this delay because the starter motor spins the crankshaft so quickly; but when kickstarting, the crank often barely rotates enough to get to that third ignition

pulse, making startup an iffy proposition.

Instead, we used a Zipper’s Thunderbolt programmable ignition (about $365, including required software and download cable) that can be adjusted to fire after just one pulse. That might not seem like much difference, but the increased ease of starting is significant. Edwards usually can start Project 100 in as little as two kicks, sometimes even in just one.

Gimme a belt, will y a?

I ride a Suzuki SV650, and I spend way too much time cleaning up the mess created by the chain drive. Why do sportbikes still use chain drive as opposed to belt drive? The advantages of no mess and vastly reduced rotating mass would seem to point to the belt as the obvious choice. What gives? Chris Condon Clearfield, Pennsylvania

The reason, Chris, is that for sportbikes and roadracers, chain drive still is best suited to the task. Yes, the O-ring chains on sportbikes can be messy if as Kevin Cameron likes to put it, “people keep squirting sticky, brown ‘mast & cable lube ’ on them as if it were still 1972. ”

For more than 100 years, chains have proven a very efficient means of power transmission. They ’re compact, they consume very little of an engine s power (generally only a percent or two) and, when adequately sized to the task and properly maintained, they ’re quite strong.

Toothed belts do, admittedly, have a lot going for them: They ’re light, quiet and require no lubricant. But they also

have limitations that make them unsuitable for sportbikes and roadracers. For one, the more power they have to transmit, the wider they must be. Below 60 horsepower or so, the requisite belt would not have to be a whole lot wider than a #630 chain; but once past that level of power, belt width would be a sportbike design problem, forcing frames, drive-pulley cases and swingarms all to be much wider on motorcycles that need to be as narrow as possible. Harley-Davidsons use belts, of course, but both the belts and the bikes are anything but narrow; and even they often are converted to chain drive once the motor is hopped up to serious horsepower levels.

What s more, belts cannot tolerate much variation in tension, a factor that limits the location of the drive sprocket relative to the swingarm pivot. This would be problematic on high-powered sportbikes and roadracers, because the relationship between sprocket and pivot is crucial to the behavior of the rear suspension during hard acceleration. And changing final-drive ratios could greatly com-

pound the problem.

Another consideration, though not so critical, is that the wider the belt, the more likely a small stone could find its way between pulley and belt. This could easily destroy enough fibers in the belt to cause its rapid deterioration and breakage.

According to the chain manufacturers, most messes are caused by people using either the wrong chain lube or too much of the right lube. The recommendations vary somewhat from one manufacturer to another, but in general, O-ring and Xring chains should be lubricated sparingly with a product designed specifically for these kinds of chains. The lube should be applied to the inside of the chain’s lower run so that as the chain rotates around its sprockets, excess lube tends to be flung outward by centrifugal force. This allows most of the excess to work its way into the outer parts of the chain rather than flying off onto the back end of the bike.

Chain lubes consist of the lubrication medium itself-usually a slightly sticky, specially formulated oil-mixed with a > thin solvent, called a carrier, that helps the lube migrate into tight places. The carrier then evaporates, leaving behind only the lubricant. You should, therefore, lubricate the chain well before beginning a ride so the carrier can completely

evaporate; otherwise, too much of the combined material will be easily slung off when the bike is first ridden. Many riders prefer to lube their chains a fter a ride, when the chain is warm. This helps the lube penetrate into tight areas and accelerates the evaporation of the carrier. Over time, some lube will still accumulate on the rear wheel and inner fender, but judicious application of appropriate products usually limits the mess to an acceptable level.

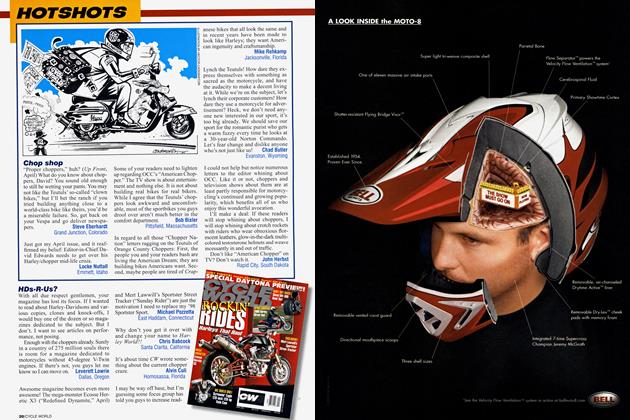

Tool Time

Two kinds of people ride dirtbikes: those who carry tools with them, and those who, on at least one occasion, have left their non-functioning motorcycle stranded alongside the trail. To help members of the second group join the first, CruzTOOLS (<cruztools.com) has introduced the DMX Tool Kit, an $80 fanny pack already equipped with many of the tools a rider might need for trailside repairs. Included are 10mm and 12mm combination wrenches, metric hex keys, a 4-in-l reversible screwdriver, locking and needlenose pliers, an 8-inch adjustable wrench, a three-way (8, 10, 12mm) T-handle, two tire irons, a feeler gauge and a sparkplug socket. Also in the kit are a small metal flashlight, a tire pressure gauge, a roll of electrical tape, a tiny tube of WD-40, five cable ties, 3 feet of mechanic’s wire and even a shop rag.

All this is packed in a mgged, 5040-Denier nylon fanny pack that zips open flat to allow

unobstructed access to the tools. There’s also a fullwidth zippered pocket on the outer flap, and the body of the pack has an even roomier zippered pocket, inside of which are two additional zippered pouches-one large, one small. The pack’s wide nylon belt is secured by a fastex buckle, and the part of the pack that contacts the rider’s backside is rubberized to keep it from shifting around.

In quality, none of these tools will compel your local Snap-On dealer to slit his wrists, but they’ll get the job done, and CruzTOOLS acknowledges that the kit does not contain everything a well-prepared trail rider might need. But that’s the reason for the generous added storage capacity. Some of the kit’s items (electrical tape, WD-40, zip ties, mechanic’s wire, etc.) can be stored in one of the zippered pouches, freeing up their elastic securing loops for your own supplemental tools. And the fanny pack seems sturdy enough to cope with everything you might stuff in it or throw at it.

What do I think of the DMX Fanny Pack, you’re wondering? Well, I hope CmzTOOLS isn’t planning for me to send it back.

-Paul Dean

What the fork?

I have a simple question, one that occurs to me occasionally when reading a review. What makes a fork an “inverted” type? Why has that particular configuration been so named? Bill Schmidt

Fairfax, Virginia

Each leg of a telescopic fork consists of two basic components: A male tube that fits into and moves up-and-down in a female slider leg. On a “conventional” fork-the basic design of which dates back more than half a century-the slider leg is on the bottom and holds the axle, while the inner tube, or stanchion, is secured in the triple-clamps. Back in the 1970s, as the suspension travel on motocross and other off-road bikes gradually kept increasing, a new problem arose: The exaggerated length of the stanchion tubes that were necessary to provide nearly a foot of frontwheel travel made it difficult to prevent the wheel from being easily deflected sideto-side over rough terrain. The engineers tried many tricks to make the forks less likely to twist in this manner, including knurling the parts of the stanchion tubes that were pinched by the triple-clamps, but most of those were Band-Aids that only saw limited success.

This prompted some clever suspension engineers to, in essence, turn the fork upside-down—that is, clamp the female sliders in the triple-clamps and attach the axle to the male stanchion tubes. The significantly larger diameter of the slider legs provided the triple-clamps with much more clamping area, thereby greatly increasing the radial stiffness of the fork assembly. And although the axle then bolted to the stanchions, which are smaller in diameter than the sliders, the method of attachment-a sizable axle tightly clamped on both sides-prevented the tubes from twisting more than a negligible amount.

Initially, no one seemed to know what to call these forks, so most people simply referred to them as “upside-down. ” They soon also came to be known as “inverted. ” And not long ago, someone decided that since the male tube on an upside-down fork is now what moves up-and-down, having assumed the role formerly held by the female slider, such suspensions should now be termed “male slider. ”

Break-in or brea kin9?

I have heard what seems like a million different ways to break-in a new bike. I’ve been told everything from ride it like you stole it, break it in on a dyno and follow the owner’s manual-although some people claim the latter is the worst technique. Please advise me of what to do because I just don’t know what is correct. I’m so confused! Kristian de Lespinois

Prescott Valley, Arizona

Ask yourself who or what you should logically believe here. Is it some guy who claims to know the “real” secret of

FEEDBACK LOOP

I don’t know why you people even bothered to test the AirBoz (February, 2005) or argue its ineffectiveness with Keith Hoekstra (“TidyBoz,”

April Service). Anyone who stayed awake through Physics class knows you can’t make energy; you can make it change forms, but you can’t create it. This is why the AirBoz cannot possibly work. The energy needed to spin the unpowered fan can be provided only by the incoming air, and that means the incoming air has less energy than it otherwise might have by the time it reaches the combustion chambers. Done deal.

No argument. Not negotiable. So, the people who are making and selling the AirBoz either are scamsters or were dead asleep and drooling on their desks throughout most of high school. Cycle World should be ashamed for giving such a foolish product the honor of an evaluation.

Alan R. Sypolt Huntsville, Alabama

Your assessment of energy is right on the mark, Alan, but I think you 've missed the point of product evaluations. Their purpose is to inform readers of the good and the bad of products through hands-on use by the editorial staff. If we happen to know beforehand that a product can't even come close to meeting its manufacturer ’s claims (which was precisely the case with the AirBoz), we feel an even greater responsibility to test it and report the results. If we were to assume a we-never-met-aproduct-we-didn ’t-like attitude and only published evaluations that were positive, there would be no point in doing them.

breaking-in a new motor? Is it any of the wives ’tales you 've heard on the street? Or is it the advice of the company that was smart enough to design, engineer, test and build the engine-and that has the most to lose if its advice is wrong? That’s a nobrainer if 1 've ever heard one.

Used to be, years ago, that the breakin period and procedure were much more critical than they are today. Advances in metallurgy, manufacturing and lubrication have all helped produce engines that are not so fussy about break-in. The manufacturers understandably take a conservative position, since they would have to bear the massive expense of repairing thousands of bikes if their recommendations were wrong; but through extensive testing and long experience, they know what it takes to achieve the best break-in. You could probably get away with an aggressive break-in without causing any problems or shortening the engine ’s life, but why risk it? Just follow the manufacturer ’s recommendations.

Many of the people who adhere to the “ride it like you stole it’’ philosophy have based their opinions on the way new or rebuilt competition engines are dealt with. Race motors usually undergo a very short break-in that’s much more aggressive than the procedure you might use with a street engine. This is so for two reasons: 1) Racers generally don’t have time to log 500 or WOO miles on a new engine; and 2) they aren 't concerned with the engine ’s ability to last many years and thousands of miles. In some cases, new race engines are fired up, run through a heat cycle or two, have their oil changed and are ready’ for the track.

Battery Bandit

I can’t keep the battery charged in my 2002 Suzuki Bandit 1200. Even when the bike just sits overnight, the battery usually doesn’t have enough juice to turn the starter motor. The only way it will start in the morning is if I hook up my Battery Tender the night before. My dealer replaced the regulator last month, but that didn’t help at all, and I replaced the battery last week, but it still goes dead overnight, just like before. If I bump-start the bike in the morning, it will run just fine all day and charge the battery, but if it sits more than about 10 hours, it won’t fire up with the electric starter. Please help! I’m not real sharp with electrical stuff, but at this point, I’m willing to give anything a try.

Eric LaSalle Appleton, Wisconsin

Obviously, something is draining the Bandit’s battery when the ignition is turned off, and from this distance, I have no idea what the culprit might be. Track>

ing down an electrical problem usually isn't on anyone ’s list of fun activities, but this one could actually be comparatively simple and straightforward. It involves performing a test using a multimeter that has a 10-, 15or 20-amp DC setting.

First, make sure the ignition switch is turned off and remains so throughout the test. Unhook the battery’s ground cable, and with the multimeter turned off, connect the meter’s red (positive) lead to the ground post on the battery, and clip the ground (black) lead of the meter to the battery cable. Now switch the multimeter to the aforementioned DC amp position and the meter will display a current reading. If the draw is large enough to drain the battery overnight, the meter should show at least 1 full ampere of current, perhaps even more.

To determine which component is at fault, start unplugging or disconnecting electrical components one at a time— again, always with the ignition turned off. Begin with the components that are easiest to access and unplug them one at a time, observing the multimeter’s reading after each disconnect. When the meter reading drops to zero, the component you just disconnected will be the source of the battery drain. What to do then depends on the nature of the problem-frayed wire, shorted internal circuit, etc.-which will determine if you repair it or replace it. Just be patient, and you will eventually find the gremlin.

Tick, tick, tick

I’ve never read anything in your magazine about the loud valve-ticking problem on the Yamaha FJR1300. I have the opportunity to buy one, a very slightly used 2004 model in like-new condition, but after reading about this ticking problem on the Internet, I’m reluctant to go ahead with the purchase. You folks and all the other motorcycle magazines have raved about the F JR, but no one seems to mention anything about this problem, and many of the comments on the Internet claim that even Yamaha won’t acknowledge the ticking. Is this problem real, and if so, should I buy the bike? Please help; I want to buy a bike, not a big repair bill. Anthony Metrano Cedar Rapids, Iowa

I’ve received quite a few e-mails from F JR 1300 owners who claim their bikes have an exceptionally loud ticking noise emanating from the camshaft area. Quite a few of those owners have had the engine inspected and found that the noise is the result of excessive wear between the valve and valve guide. And many of them claim that when they have taken the bike to their

Yamaha dealer, they’ve either been told that “they all do that, ” or that Yamaha has not issued a recall or service bulletin, so any repairs will not be covered unless the bike is still in its original warranty period. In some instances, the owner has had to pay full price to get the engine repaired.

Now, you have to understand that for the most part, editors of motorcycle publications are the last people on Earth that manufacturers wish to talk to about problems with their bikes-especially if a company is hoping to keep a problem under the radar. So, when I contacted Yamaha about the F JR1300 situation, not only did it take a while to get a reply, the people I spoke with claimed they had never heard of such a problem.

But I did eventually get a response. The official wordfrom Yamaha is that the company acknowledges the existence of the valve-ticking problem, but claims that it has occurred only on a tiny percentage of the FJR1300s that have been sold. My contact said that of the more than 15,000 units that are on the road, only 40 suspect bikes have been identified, which is less than three-tenths of one percent. In the world of mass-produced motor vehicles, that’s considered a very low failure rate, far too small to warrant an official recall.

I was told that any F JR 1300 owner who thinks he or she has this problem should take the bike to an authorized Yamaha dealer for a no-cost repair. If the dealer refuses to acknowledge the problem, or admits it but refuses to repair it under warranty, the owner should then contact Yamaha ’s Customer Service Department. The company will then arrange for one of its service representatives to meet with both the owner and the dealer to rectify the matter. □

Got a mechanical or technical problem with your beloved ride? Can’t seem to find workable solutions in your area? Or are you eager to learn about a certain aspect of motorcycle design and technology? Maybe we can help.

If you think we can, either: 1) Mail a written inquiry, along with your full name, address and phone number, to Cycle World Service, 1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach, CA 92663; 2) fax it to Paul Dean at 949/631-0651; 3) e-mail it to CW1Dean@aol.com; or 4) log onto www.cycleworld.com, click on the “Letters to the Editor” button and enter your question. Don’t write a 10-page essay, but if you’re looking for help in solving a problem, do include enough information to permit a reasonable diagnosis. And please understand that due to the enormous volume of inquiries we receive, we cannot guarantee a reply to every question.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue