RACE WATCH

BACK IN THE USA

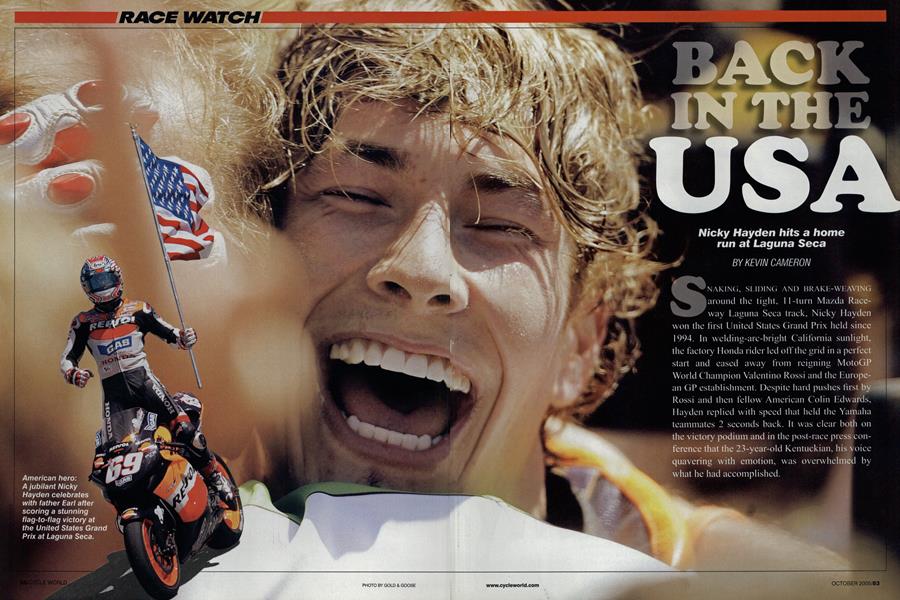

Nicky Hayden hits a home run at Laguna Seca

KEVIN CAMERON

SNAKING, SLIDING AND BRAKE-WFAVING around the light. 11-turn Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca track, Nicky Hayden won the first United States Grand Prix held since 1994. In welding-are-bright California sunlight, the factory Honda rider led off the grid in a perfect start and eased away from reigning MotoGP World Champion Valentino Rossi and the European GP establishment. Despite hard pushes first by Rossi and then fellow Ametican Colin Edwards. I layden replied with speed that held the Yamaha teammates 2 seconds back. Ii was clear both on the victory podium and in the post-i~ice CSS Con ference that the 23-year-old Kentuckian, his voice qua\'cring with emotion wa' ov~i whLlmpd by what he had accomplished. I

At the time of the last USGP, 190-horsepower 500cc two-strokes were the top class. Now, it is 990cc four-strokes producing as much as 250 hp, with top speeds of more than 200 mph.

In two previous years on Honda’s Repsol squad, Hayden has learned the circuits, food and cultural contrasts, but frustratingly scored only one podium finish. Some felt he was locked into a dirttrack style that would forever condemn him to fatigued tires at half-distance with no strategy for improvement.

Will his Laguna win finally pull the cork from his talent? Perhaps what we saw was a breakthrough in developing his style.

Such fast motorcycles turn Laguna into one nearly continuous comer. Only the mn uphill to the Corkscrew from Turn 6 can be called a straight, yet even there, power must be limited at the hill’s crest. Former 250cc World Champion Marco Melandri, currently second in points to Rossi, said. “It don't close the throttle, I jump both tires!" Back in the 1990s, Suzuki crew-chief Stuart Shenton told me that a 500 spent less than 3 percent of its time at full throt tie on a Laguna lap--and MotoGP 990s have 30 percent more power!

Perhaps because of this constant turning, the two Suzuki GSV-Rs of John Hopkins and Kenny Roberts Jr. were at or near the top of the practice order on Friday morning. Their bikes, long lacking in acceleration and top speed, have therefore been optimized for high comer speed. But an even stronger determinant of speed appeared: previous Laguna Seca experience. This added Hayden, ex-World Superbike Champion Troy Bayliss, Alex Barros (who raced the two-stroke Cagiva at Laguna in the early Nineties) and Edwards to the mix. Who can forget the stunning Bayliss/Edwards WSB battles here in ’02?

No rider can solve Laguna on a simple textbook basis-laying out the obvious lines of maximum radius, clipping every apex tight and swinging out to the very edge of pavement on exit. Laguna has bumps and ripples, put there by the braking and acceleration of heavy racing cars. The bump on the exit of Tum 11, for example, once decided an AMA Superbike race between Hayden and current series champ Mat Mladin. Hayden got the drive up the hill to the finish line as his softer setup hooked up over the bump while Mladin’s tire went up in smoke. Another famous bump lurks on the exit of Turn 5. Then there is the Corkscrew itself, where a rider must brake from high uphill speed, maintain grip over the crest, turn almost 90 degrees left while pitching steeply downhill, then pull out hard to the right at the bottom and accelerate again. First-time riders are confused by combined pitch and roll, which have nonintuitive consequences that take time to leam. Melandri said, “For sure, the Corkscrew is completely different. It’s nice, but strange. I try to follow the American riders-they are so fast there. I try to be faster, lap by lap, but it is difficult and I make mistakes.”

Remarkably, MotoGP engines have a very wide useable rpm range. Seen on the TV feed from tiny on-bike cameras, revs ranged from 6800 to 15,000. At the Corkscrew, I could hear this as riders held a single gear from the entry all the way down the hill and beyond the top of their roll from right to left afterward. It’s a much wider band than Eve heard here from Superbikes. Which ones are the real racing engines? This wide range emphasizes the engineering that has gone into making these super-powerful machines rideable as well as fast.

Indeed, Edwards expressed the view that these bikes are easier to ride fast than Superbikes because of the electronics (electronics is a catch-all term for the rider-friendliness of MotoGP en gines). Melandn disagreed: "I think Cohn doesn't remember so well Superbike." As for the fabled electronics, I could hear soft, irregular misfiring from the otherwise very loud Kawasakis as they accelerated. What could this be? No one would try to limit power by cutting out

cylinders. That would produce upsetting jerkiness. Initially, when torque has to be reduced, it's done by electronic spark retard, but when even more reduction is needed-especially with this year's fuel capacity cut from 6.3 to 5.8 gallonswhat better way than to momentarily lean out the fuel mixture? What I was -~ hearing may have been the onset of lean misfire as the anti-spin system reduced fuel delivery. The Kawa sakis have been greatly improved by a switch to close firing order (this notionally increases tire grip by letting the tire lay down a fresh footprint for each torque pulse), and they appeared to have stronger bottom-end acceleration than the traditionally power-laden Ducatis, Currently no major team is still running a “screamer” engine with an evenly spaced firing order. Ducati began in MotoGP with both twinand four-pulse engines, with riders choosing the latter because of power losses involved in narrow firing order at the time. When the twinpulse concept was re-tested after further power development, it was found to be superior.

An undercurrent of reserve about track safety co-existed with enthusiasm for the return of the USGP. European tracks used to be extremely dangerous, with steel railings and walls aplenty. More recently, the rapid popularity growth of racing there has provided funds to stop the once-inevitable annual “harvest” of top riders. Wide corner runoff areas are now nearly universal, and MotoGP rules re quire that emergency vehicles be able to reach fallen riders at any point without crossing or running on the track itself. These things have now become funda mental, but are not yet the norm in the U.S. When Edwards, who hadn't ridden at Laguna since `02, went out for first practice, he said to himself, "Whoa! Did they move the walls in? This looks really scary!" Yet, in response to rider safetycommittee requests, $2 million (funded by Yamaha) had been spent widening runoff and moving the pedestrian bridge near Rainey Curve closer to the Corkscrew so its abutments cannot be hit.

What do riders not like? Melandri replied, “The walls are too close, and the surface is bumpy. It’s not really good for MotoGP.” Cresting the hill into Tum 1, he said, “You don’t jump, but the bike becomes very light.” Ambulance access is still well below Euro-standard, and in Turn 6, the only way to provide runoff would be to build a 200-foot-wide redwood deck cantilevered over the valley below, then spread gravel on it. Earlier in the week, Melandri had summed up Laguna by saying, “If we race by the same regulations we have in Europe, we cannot be here.” Yet having said that, he made a genuine effort. You could almost hear Doma officials, their fatherly anns around the riders’ collective shoulders, saying,

“This race is very important for our marketing plan, so just cool it on the safety angle, okay?”

By Friday’s close, Hayden had top time, followed by a sliding Bayliss, a hardworking and steady Max Biaggi, Barros, Hopkins and Edwards. Rossi was down in ninth after two long pit sojourns. Would the Europeans suddenly climb the ladder once their crews had implemented Friday’s “testing” in hardware? Or would Laguna Seca riding experience remain the only key?

On Saturday morning, little changed. Rossi and Barros lapped together and I could hear engine rpm fall and rise as their bikes rolled from full right lean to upright to full left lean-an effect caused by the difference in rolling radius from sidewall (smallest) to centerline (largest). I could see the Kawasakis’ swingarm geometry work, the rear of the bikes lifting as the riders throttled up. Bayliss’s Honda was set up as his Ducati WSB had been in 2002, with large, soft suspension motions making his bike “wallow-slide.” Hayden was quickest and getting quicker.

In afternoon qualifying, the Honda rider repeatedly lowered his time, reaching 1:22.670. Rossi, who spent most of qualifying outside the top five, finally squeezed out a 1:23.024 for second spot. The last minutes of qualifying were dramatic as riders watched the television monitors and chose their moment to go out on qualifying tires for a last push. Third, fourth and fifth on the grid would be Barros, Bayliss and Edwards. Hayden’s pole position was his first in MotoGR

I spoke with Ducati’s Corrado Cecchinelli. asking him if the company’s engine philosophy (as told to me by Claudio Domenicali two years ago) had changed.

This was to build the most powerftil en gine possible, then smooth its delivery using electronics. Cecchinelli replied that although Ducati acknowledges engine de livery must be as smooth as possible for good control in off-corner acceleration, it also takes power to win in this class. Duc ati, owing to the remarkable rpm capa bility of its desmo valve drive system, is in a good position to make this power. He also noted that it is easier to achieve good engine delivery if what he called the “natural” engine (minus smoothing electronics) was closer to being right to begin with. But as to the question? Yes, the maximum-power philosophy remains, and the big change in Ducati’s engines is to the firing order. In effect, Cecchinelli said, “We do not yet understand how close firing order works, but we will use it because it does work.”

This brings us to tires. The top seven finishers at Laguna were on Michelins, for the French company has all the top Honda and Yamaha teams. Suzuki, Kawasaki and Ducati are on Bridgestones. Why? Because last year, Makoto Tamada’s brilliant rides on Bridgestones made him the most credible future threat to Rossi. Yet this year, Bridgestones have faded in hot weather. I think of another tire-maker with Formula One experience that decided to go motorcycle racing: Goodyear. In the 1960s, excited about high-tech rubber compounding developed in its F-i work, Goodyear applied it to their first motorcycle roadracing tires. It failed. Rubber that worked in wide F-i tires overheated and gave up in motorcycle service. Only when Goodyear switched to its family of lower-tech but more heat-tolerant NASCAR compounds were they able to make successful race tires for motorcycles.

Another point is that Michelin's flex ible manufacturing system allows rapid response to special needs-probably over night. This would allow the Clermont Ferrand crew to fine-tune Sunday's tire directly from the results of Friday's and Saturday's practices. By contrast, a Due ati engineer described their tire problem as having too few choices, too many choices or no choice at all.

It’s easy to get excited about technology, but veteran Öhlins technician Jon Cornwell had a cold shower for people like me. He said that suspension is not the engineer’s dream-a science of increased grip-but is rather a means of giving the rider the “feel” he needs in order to believe it’s safe to go as fast as his talent will let him. If this were not true, all machine setups would converge toward a common solution. Wide differences in rider preferences deny this.

HRC General Manager Tsuto mu Ishii told me that Honda's re search now centers on how to char acterize exactly what engine qualitics are "tire-friendly." He said also that its engineers are morc modest to rider now," as a means of improving communication between the two. I think one and a half seasons of Yamaha dominance have been a severe blow to Honda's magisteri al certainty that it is the motorcycle that wins races. Race and learn. Last year, the Hondas had increased power, while Yamaha had too little. Jere my Burgess, Rossi's engineer, told me that now, "The Hondas have a bit less power than last year, and we have a lot more." This has been seen during recent races in which Rossi's bike has for the first time been fastest on the straight (at Laguna, Hayden's RC211V clocked fast est at 160 mph). When a company or team reduces power, it does so to give a mild er torque curve that keeps the tire hooked up for faster off-corner acceleration. And so, back and forth goes the see-saw.

Technical problems can be tough, but what about social ones? Total attendance of 153,653 spectators over three days left thousands fuming over traffic delays. As we waited into Sunday evening for traf fic to move, we walked to the heli-pad to watch a fleet of 10 choppers ferry Red Bull guests and others with $175 to their next obligations. A question to a Rolex wearing track official revealed that High way 68, which runs right past the front of the track, is closed on race days until 8 p.m. at the "request of local residents." This pushed all race traffic onto inade quate former military roads which, for incredible lengths of time, did not move at all. Police ticketed motorcyclists for lane-splitting, while track officials urged riders to lane-split to move traffic along.

Was anyone actually in charge? Either there was no planning for this event, or there was “anti-planning,” for many racewatchers felt that the only visitors welcome here are golfers and buyers of art and real estate.

The race itself was worth the traffic, The Yamahas have been weak off the line this season and Hayden got a rocket start, establishing a lead he would keep to the end. On the first lap, Melandri tapped Barros in Turn 11, downing both. At the exit of Turn 2, Hayden was aggressively thrusting his bike more upright by keeping his own body low, rolling onto the best part of the tire for acceleration. By lap nine, he had a 2-second lead and thereafter increased it-not by much, but by enough to make the point. Meanwhile, Edwards moved up rapidly, passing Rossi at the entrance to the Corkscrew on lap 15.

Was this genuine drama? In the sense that an American was winning the first USGP in 11 years, it certainly was. Why wasn’t Rossi faster? Because he did not know how to go faster-learning Laguna takes time. In Europe, it is Hayden who has been behind on the learning curve, but here their roles were reversed. Over the years, the Europeans have regarded Laguna as a kind of sideshow, put on for good business reasons, but they also respect its potential for injuries. Therefore, they ride strictly within their knowledge, hoping to leave with limbs and points intact.

At the very end, Rossi closed to within a fraction of a second of Edwards, but said in the press conference that in his mind he pictured the two of them sliding in the dirt off the track-“not so good for Yamaha”-so he held position. Rossi left Laguna with 186 points and a larger leadequivalent to three race wins-than when he arrived. Hayden joined Melandri, Biaggi, Sete Gibemau and Edwards, all with nearly 100 points, one of whom will be second in this year’s championship. Why the contrast with last year, when Gibernau’s strong challenge made the season one long nail-biter? Among possible challengers, Gibemau had a tire problem in China, Biaggi started slowly, Melandri fell at Laguna and Edwards had hook-up problems until making a setup breakthrough in Holland. Completing the race’s top-five were Biaggi and Gibemau, who had both studied hard and ridden well.

Honda HRC President and Director Sugum Kanazawa has spoken of “riders of the present and riders of the future.” Most-Bayliss, Barros, Biaggi, Capirossi, Carlos Checa, Edwards, Gibemau, Roberts, Rossi and others-are riders of the present. Melandri-his career so brilliantly revived by the emotional nurturing of Team Gresini-is clearly one rider of the future, as is Hayden. Others? Hopkins rode strongly through practice and finished eighth-the top Bridgestone man. Dani Pedrosa, the 125 and 250cc star, will soon be another, although some wonder if his small size may create problems unique to him in MotoGP. He is a fighter who, like Gary Nixon, doesn’t just ride fast, he races.

Nicky Hayden’s victory lap was a singular occasion. He carried his father Earl on the seatback (probably very hot!) for all to see. Asked by the press to give a oneword description of his weekend, Hayden just looked wide-eyed and speechless. Edwards, seated to his left, spoke for him. “Fairytale,” he said evenly. So it was.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

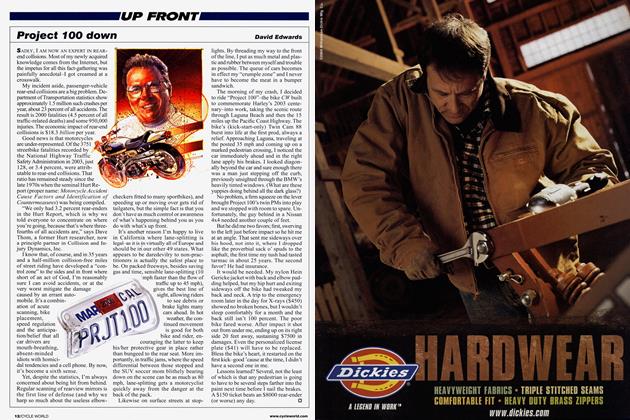

Up FrontProject 100 Down

October 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsMad Dogs And Irishmen

October 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCSausages And Steel

October 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

October 2005 -

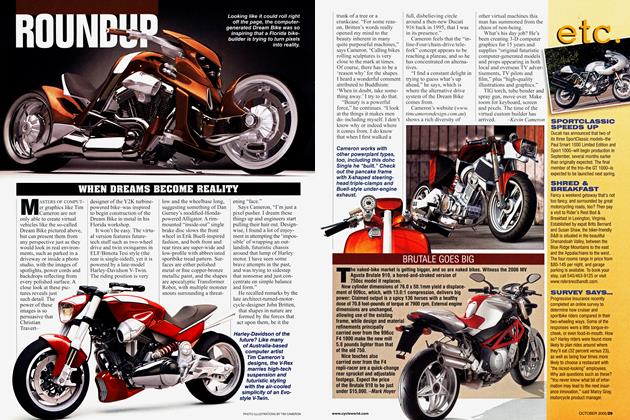

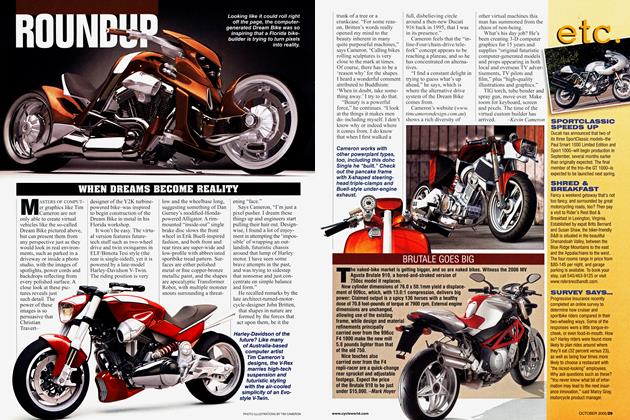

Roundup

RoundupWhen Dreams Become Reality

October 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupBrutale Goes Big

October 2005 By Mark Hoyer