Mr. Daytona Sr.

UP FRONT

David Edwards

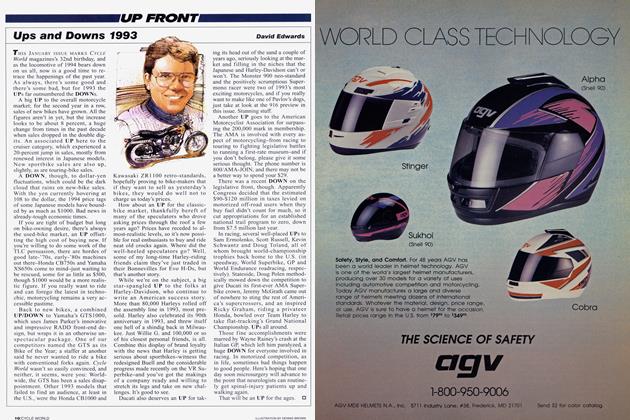

I'VE TURNED OVER MY USUAL DAYTONA 200 soapbox this year to Kevin Cameron, who comments on the fate of what was once America's Great Race in this issue's Race Watch, but first a couple of observations:

It was just plain wrong to see one of our best roadracers, Jamie Hacking, dressed in civvies and sitting beside his pretty wife in the grandstand bleachers Saturday as the Superbike race-a mere sideshow this year-was flagged off. Hacking’s Yamaha squad, its races run for the week, had packed up after Thursday’s Supersport contest. By the time the 200-miler got the green,

Jamie and Rachel had left the scene, too, no doubt not interested in seeing how badly the trio of factory Hondas would cane an otherwise privateer field.

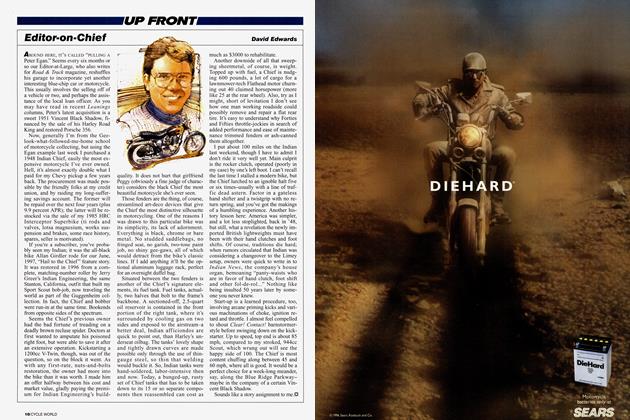

As usual, Honda number one Miguel Duhamel rode a calculated and flawless race-lack of opposition notwithstanding-to take the checkers, his fifth Daytona 200 win, tying him with Scott Russell for the title of Mr. Daytona. No fault of his own, but I can’t help but wonder if Duhamel’s record-tying win will forever be marked with an asterisk, Roger Maris in a Shark helmet and Joe Rocket leathers.

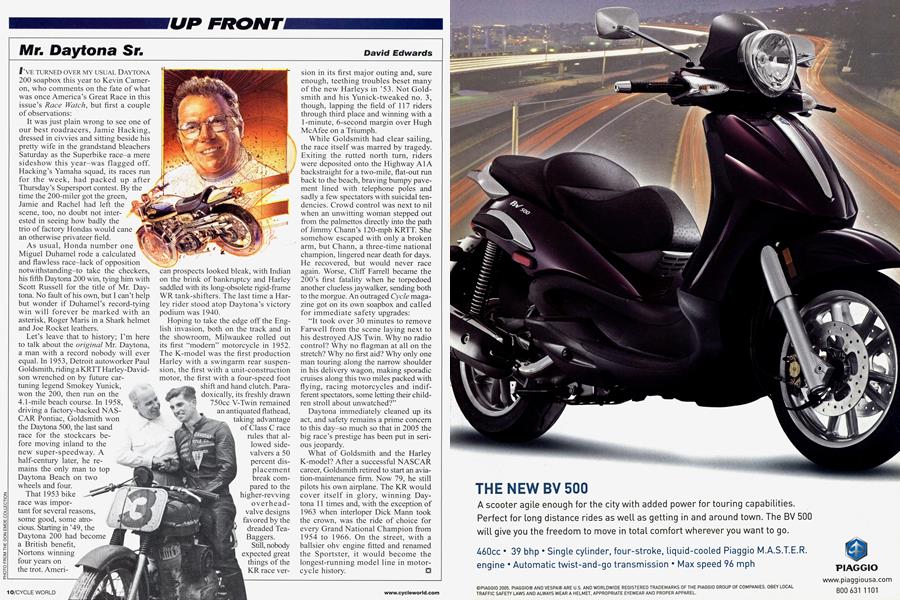

Let’s leave that to history; I’m here to talk about the original Mr. Daytona, a man with a record nobody will ever equal. In 1953, Detroit autoworker Paul Goldsmith, riding a KRTT Harley-Davidson wrenched on by future cartuning legend Smokey Yunick, won the 200, then run on the 4.1-mile beach course. In 1958 driving a factory-backed NASCAR Pontiac, Goldsmith won the Daytona 500, the last sand race for the stockcars before moving inland to the new super-speedway. A half-century later, he remains the only man to top Daytona Beach on two wheels and four.

That 1953 bike race was important for several reasons, some good, some atrocious. Starting in ’49, the Daytona 200 had become a British benefit,

Nortons winning four years on the trot. Ameri-

can prospects looked bleak, with Indian on the brink of bankruptcy and Harley saddled with its long-obsolete rigid-frame WR tank-shifters. The last time a Harley rider stood atop Daytona’s victory podium was 1940.

Hoping to take the edge off the English invasion, both on the track and in the showroom, Milwaukee rolled out its first “modem” motorcycle in 1952. The K-model was the first production Harley with a swingarm rear suspension, the first with a unit-construction motor, the first with a four-speed foot shift and hand clutch. Paradoxically, its freshly drawn 750cc V-Twin remained an antiquated flathead, taking advantage of Class C race mies that allowed sidevalvers a 50 percent displacement break compared to the higher-revving overheadvalve designs favored by the dreaded TeaBaggers.

Still, nobody expected great things of the KR race ver-

sion in its first major outing and, sure enough, teething troubles beset many of the new Harleys in ’53. Not Goldsmith and his Yunick-tweaked no. 3, though, lapping the field of 117 riders through third place and winning with a 1-minute, 6-second margin over Hugh McAfee on a Triumph.

While Goldsmith had clear sailing, the race itself was marred by tragedy. Exiting the rutted north turn, riders were deposited onto the Highway Al A backstraight for a two-mile, flat-out mn back to the beach, braving bumpy pavement lined with telephone poles and sadly a few spectators with suicidal tendencies. Crowd control was next to nil when an unwitting woman stepped out from the palmettos directly into the path of Jimmy Chann’s 120-mph KRTT. She somehow escaped with only a broken arm, but Chann, a three-time national champion, lingered near death for days. He recovered, but would never race again. Worse, Cliff Farrell became the 200’s first fatality when he torpedoed another clueless jaywalker, sending both to the morgue. An outraged Cycle magazine got on its own soapbox and called for immediate safety upgrades:

“It took over 30 minutes to remove Farwell from the scene laying next to his destroyed AJS Twin. Why no radio control? Why no flagman at all on the stretch? Why no first aid? Why only one man touring along the narrow shoulder in his delivery wagon, making sporadic cruises along this two miles packed with flying, racing motorcycles and indifferent spectators, some letting their children stroll about unwatched?”

Daytona immediately cleaned up its act, and safety remains a prime concern to this day-so much so that in 2005 the big race’s prestige has been put in serious jeopardy.

What of Goldsmith and the Harley K-model? After a successful NASCAR career, Goldsmith retired to start an aviation-maintenance firm. Now 79, he still pilots his own airplane. The KR would cover itself in glory, winning Daytona 11 times and, with the exception of 1963 when interloper Dick Mann took the crown, was the ride of choice for every Grand National Champion from 1954 to 1966. On the street, with a ballsier ohv engine fitted and renamed the Sportster, it would become the longest-running model line in motorcycle history. □