CUTTING EDGE

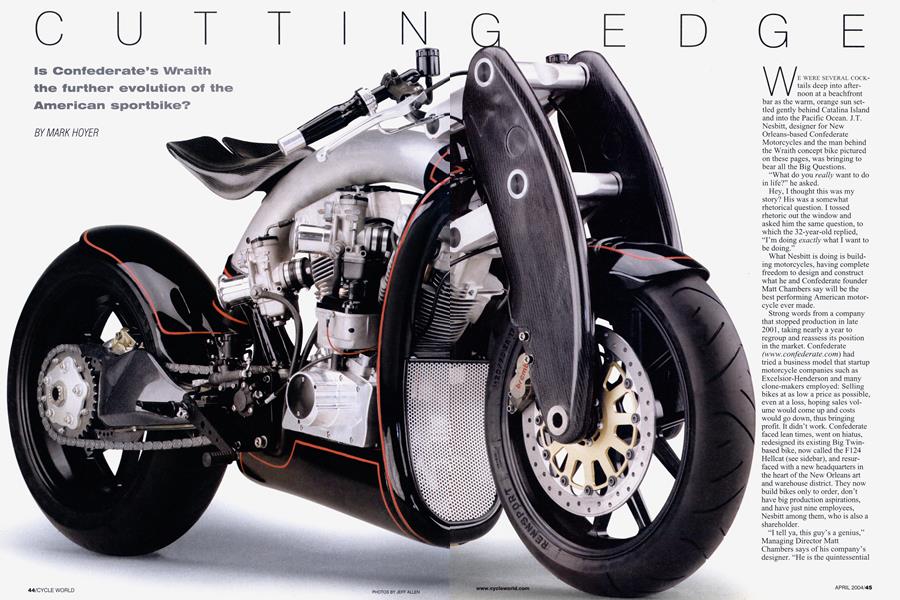

Is Confederate's Wraith the further evolution of the American sportbike?

WARK HOYER

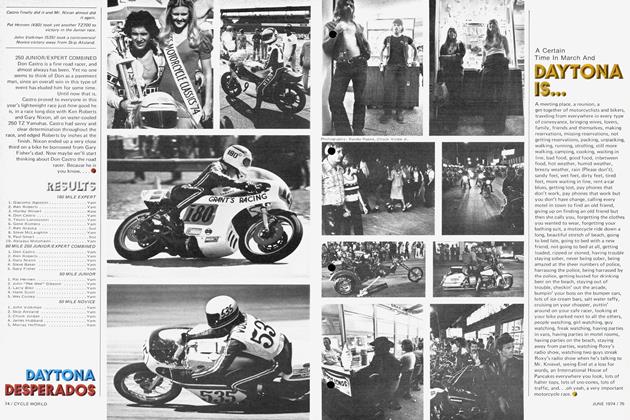

WE WERE SEVERAL COCKtails deep into afternoon at a beachfront bar as the warm, orange sun settled gently behind Catalina Island and into the Pacific Ocean. J.T. Nesbitt, designer for New Orleans-based Confederate Motorcycles and the man behind the Wraith concept bike pictured on these pages, was bringing to bear all the Big Questions.

“What do you really want to do in life?” he asked.

Hey, I thought this was my story? His was a somewhat rhetorical question. I tossed rhetoric out the window and asked him the same question, to which the 32-year-old replied, “I’m doing exactly what I want to be doing.”

What Nesbitt is doing is building motorcycles, having complete freedom to design and construct what he and Confederate founder Matt Chambers say will be the best performing American motorcycle ever made.

Strong words from a company that stopped production in late 2001, taking nearly a year to regroup and reassess its position in the market. Confederate (www.confederate.com) had tried a business model that startup motorcycle companies such as Excelsior-Henderson and many clone-makers employed: Selling bikes at as low a price as possible, even at a loss, hoping sales volume would come up and costs would go down, thus bringing profit. It didn’t work. Confederate faced lean times, went on hiatus, redesigned its existing Big Twinbased bike, now called the F124 Hellcat (see sidebar), and resurfaced with a new headquarters in the heart of the New Orleans art and warehouse district. They now build bikes only to order, don’t have big production aspirations, and have just nine employees, Nesbitt among them, who is also a shareholder.

“I tell ya, this guy’s a genius,” Managing Director Matt Chambers says of his company’s designer. “He is the quintessential motorcycle person. He doesn’t own a car. He really wants to make a difference in the world through his motorcycle art. He can weld, he can machine, he doesn’t just draw the motorcycle, he makes it with his hands. He and one other guy went in the back of the shop and built the Wraith.”

When you look at the concept mockup of the company’s forthcoming new bike, it is hard not to agree that Nesbitt, who has a degree in fine arts and was previously a working sculptor, is a gifted motorcycle designer/builder.

“This is not a bicycle with an engine attached,” says Nesbitt, voicing his views on current bike design. “What I wanted was for the engine and chassis to speak the same language. In this respect, what does the frame of a GSX-R have to do with the engine? That motorcycle is brilliantly engineered, but in terms of design, it’s a collection of visual short stories, not a novel.”

So the goal was to meaningfully relate all the pieces of the Wraith (Scottish for “ghost”), particularly the main elements of frame and engine.

“Imagine the two cylinders you see as part of a sevencylinder radial aircraft engine,” Nesbitt says. “Basically, it’s a section of a circle. The frame’s arc is the section of a circle of slightly larger radius, its center concentric with the engine’s crankshaft.”

At this point the Shreveport, Louisiana, native went to his charcoal pencils, sharpening one with a knife pulled from the pocket of his rocker-style duds, and proceeded to sketch what he sees as the core vibe of the bike, a drawing that buzzes with energetic, interrelated geometric forms. It was not, strictly speaking, a motorcycle.

“I have thousands of these drawings,” he said. “The drawing is a system of shapes and lines that has a proportion that exists independently of the matrix of the motorcycle. In other words, you could take these forms and apply them to kinetic sculpture and I think they would still be beautiful.”

This isn’t the kind of talk you get from a typical motorcycle designer. Most corporate product designers do have the freedom to draw whatever they fancy, but when it comes time to translate ideas into a saleable product, the constraints of volume manufacturing and federal regulations usually radically alter the pure forms of which they dream, morphing the idea into some bastardized shadow of its former concept. After a time, the corporate mentality, the legal constraints, often infuse the core design ethic of the person with the pencil.

"Who wi/I be most affected by the Wraith? Harley Davidson. I think we are on the cusp of a renaissance of American design, and motorcycle design in this country is not defined by Harley-Davidson." -Ji Nesbitt

Not so at Confederate, which because of its low-volume status isn’t yoked to legal departments, manufacturing concerns or DOT regs. This is one of the reasons that Confederates have always been different, from the first “Gl” bikes Cycle World tested in 1996 to the most recent Hellcat. In the past, we have found the riding experience distinct, powerful and much removed from what the basic clone-type spec might suggest. While the usual motor from Confederate is indeed a big-inch Harley-style V-Twin, pretty much everything else, from the frame to the proprietary compact transmission to the wheels and suspension, is a radical departure for an American-made motorcycle.

Confederates are like a fine single-malt scotch: To some, the best peat-fired versions from the Scottish Highlands bum your throat and taste like smoldering garbage-tmck tires; to others, they are the most wonderful and subtle musical combinations of flavors on the planet. And, like scotch, even if you don’t actually like it, in sufficient quantities it nonetheless will have a profound effect on your world, at least until the buzz wears off.

Nesbitt is still buzzed.

“The bike spoke to me,” he relates about riding a Confederate for the first time. “I feel like they have a soul, that they are imbued with the passion of the people who build them.”

Nesbitt is nothing if not passionate. With this passion, he combines artistic inspiration that comes from two key individuals: Alexander Calder and John Britten. The late Mr. Britten is well-known among motorcycle people for building in the early 1990s the famous VI000 twin-cylinder racebike essentially in his New Zealand shed. Who is Calder? “He took sculpture to the next level in the 1930s by inventing the mobile,” says Nesbitt. Okay, and a pop-art collection of hanging shapes is important...why exactly? “Because it had to work, it had to have balance,” he explains.

Which, of course, brings us back to Confederate. “We build kinetic sculpture,” says Nesbitt.

Still, it is a motorcycle, and for his part, Nesbitt is a selfdescribed “bobber guy” and rates the Wraith a modern board-track racer. In the metal, the bike hums with the DNA of his own flathead Harley bob-job (featured in “American Flyers,” CW, May, 2002), but is all modernist, less-is-more sparseness using the latest materials set in stark, elemental forms, with more than a hint of the early 20th-century Bauhaus design school.

There are no covers on anything. Each part is what it is and is what it does. The single-tube frame of 4-inch aluminum carries engine oil. The front cowl houses fuel in a tank that runs under the engine. The single-sided swingarm on this model is a Ducati piece that has been flipped over to get the chain on the right-hand side, but Confederate is working on its own design in carbon-fiber.

Why the girder fork?

“Because it had to be that way,” Nesbitt declares. “The steering neck had to be as low as possible (to maintain the concentric circle idea), so it had to be right on top of the cylinder head. But a conventional front end would foul the engine, so we had to use a carbon-fiber girder.”

The fork is a good example of Nesbitt doing what he calls “listening to the material” when he designs pieces, because it doesn’t fit the visual signature of what we’ve come to expect a girder fork to look like-it seems visually heavy and slabsided. But materials often dictate design, and just as bikemakers of the 1920s and ’30s made spindly, thin rods out of ferrous metals to build as rigid, light, durable and functional a fork as they could, so Chambers and Nesbitt have used the materials of their day to accomplish the same goals of rigidity and functionality, unadorned.

"I am compelled to do this. Really, there is no in between. / am going to design motor cycles, or I'm going to be a waiter..." -JI. Nesbitt

“We chose not to decorate the fork blades,” he says. “Once you do that, once you ‘decorate,’ you’re cheating the holistic design ethic.”

You will notice this bike does not use a Big Twin Harley-style engine. The first 13 Wraiths will be $75,000 limited-edition models to commemorate Confederate’s 13 years in business. These will use iron-barreled XR1000 engines with four-speed gearboxes. The advantages of the XR motor over a big Evo or Twin Cam engine are manifold. Foremost is that it is more compact, a unitized engine and transmission that in addition to being physically smaller and lighter, is also more stout. The use of four cams allows the pushrod runs to be straight (contrary to the angled arrangement on Evo Big Twins and Twin Cammers), meaning the engine can turn higher rpm without throwing loose the valvegear.

Regular production will follow the Halloween 2004 rollout of the XR-powered machine. These will use S&S-built, 100-cubic-inch, 120-horsepower Sportster-style engines, simplifying carburetion (XRs use a carb at the rear of each cylinder head) and modernizing the whole engine package as compared to the increasingly difficult to find (and more expensive) XR mill. At the same time, the identical size and performance benefits offered by the unitized bottom end and valvetrain setup are retained, which for all intents and purposes is the same on both engines.

Even the price for the “production” version falls under the if-you-have-to-ask heading at a projected $40,000. Although in these days of Jesse James and other custom builders’ $70,000-and-up world, the Wraith looks like a bit of a bargain and promises to function much better than your average chopper, thanks to sporty geometry of 27 degrees of rake and 3 inches of trail. Plus, counter to the fat-ass trend on customs that now typically feature a 200mm or wider rear tire, the Wraith will carry 180mm rubber, suggesting handling will at the very least be sporting. Straight-line performance should be exhilarating, as the dry weight will be under 400 pounds.

As important as the aesthetics of the Wraith are, performance is equally fundamental to the bike’s mission.

“The core foundation of our company is to build highperformance American motorcycles,” declares Nesbitt. “This bike takes you back to when ‘American’ and ‘highperformance’ made sense in the same sentence, when Indian won at the Isle of Man and Harley won at Daytona. Hopefully, we can have our thumbprint on high-performance American motorcycles.”

Chambers says they really aren’t looking to leave a huge thumbprint, either, maybe 50 or 60 bikes per year, in search of only that many passionate, well-monied motorcycle enthusiasts.

“We are going for something like Brough Superior or Crocker, that very small niche in the marketplace that can only be justified by emotion,” says Chambers. “To want one of our bikes, you just can’t get there with your accountant in the room. First, you have to have the money, then you have to have the emotion. You can’t justify it any other way.”

It’s true. One of the elements that makes the Wraith so appealing is the freedom it represents, freedom in design terms and freedom for those who build it. Maybe it is so striking partly because the people who build it are doing exactly what they want to be doing in life. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontArt of the Chopper

April 2004 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Age of Tough Engines

April 2004 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCCutting It Close

April 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

April 2004 -

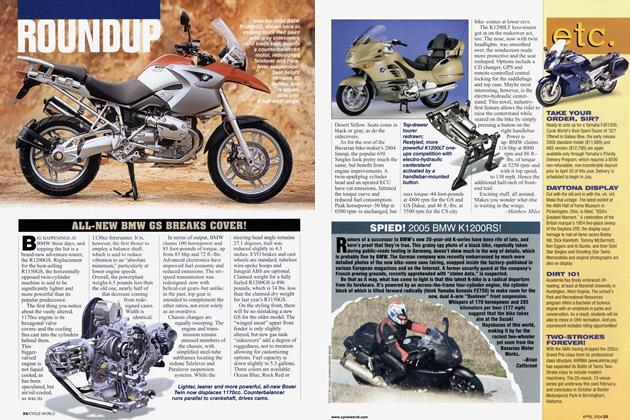

Roundup

RoundupAll-New Bmw Gs Breaks Cover!

April 2004 By Matthew Miles -

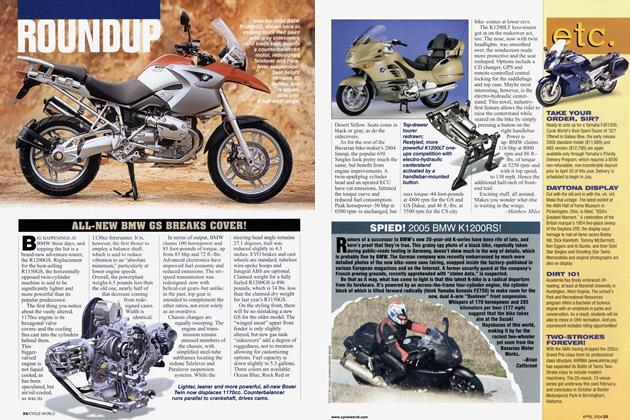

Roundup

RoundupSpied! 2005 Bmw K1200rs!

April 2004 By Brian Catterson